When I was asked if I would be interested in writing a column on contemporary sacred art for Omnes, I immediately thought it would be a difficult but exciting job. The editor of the magazine told me that the idea would be to feature, in each article, an artist who, in my opinion, could be considered interesting from a Catholic perspective. Let me begin by saying that my way of looking at contemporary sacred art is not made up of certainties, but rather of an awareness of the complexity of the subject.

Trends in sacred art

Christian sacred art, that which contributes to the creation of liturgical space, or that which serves as an aid to collective or personal devotion and prayer, is an art that has a precise purpose and touches very sensitive aspects for communities and individuals. The Western tradition, that is, the Catholic tradition, has allowed, unlike the Orthodox tradition, great flexibility to experiment and adopt styles that have changed with time and space. Each artistic revolution, each style, has expressed its own "way" of dealing with the sacred, both in terms of liturgy as of devotion.

But more recent Western art seems to have been less interested in the sacred, although it has developed currents, movements, artists who have proposed an art that, more or less accepted by critics and the public, testifies to a presence. Some of these artists have meditated with the subject of the sacred, sometimes in a provocative and even irreverent and disrespectful way, in many other cases with a sincere interest.

Faced with contemporary artistic movements, and with some Christian artists who are interested in traditional sacred art, a contrast has arisen that has been reflected in the Christian faithful and in those who have the responsibility of channeling the new artistic production: on the one hand, those who believe that we must be open to new proposals, to a new sensibility that, on the other hand, is far from being univocal, being as fragmented as the contemporary art scene is today; others, instead, have looked backwards, thinking that we must return to the art of the 19th century, figurative, narrative, in line with the Western tradition.

The latter, that is, those that for convenience we will call traditional, refer in turn to different traditions; some look to the Christian East, to the icons, others to the Middle Ages, others to the Renaissance, or to the 19th century, which was also the era of neo-Gothic, neoclassical, neo-Renaissance, neo-Romanesque....

The Church's approach

I do not know what is appropriate to do today in this field, and what is not. It is up to the artists to think, to propose, to reflect, obviously together with their principals, the religious communities of reference, and also with those who have studied the subject, for example by teaching the subject of contemporary sacred art in a school of sacred art. Art is a complex phenomenon that cannot be reduced to recipes or schemes. But this does not mean that one cannot reflect and find arguments to consider that an artist, or a work, is more or less suitable for liturgical use, within the faith and also within the Western Christian tradition, in a "here" and in a "now" that varies and that also (but not only) depends on space and time.

What I have just affirmed is that Christian sacred art, in the Catholic tradition, is linked to the culture that changes with the times and places. This is argued in a magisterial document of the Second Vatican Council, which states, among other things, that the Catholic Church does not have an artistic style of reference, because the style must be the one most in keeping with the faith and the dignity of the celebration, but also in keeping with the specific cultures.

In fact, the Constitution "Sacrosanctum Concilium" states in point 123 that "the Church has never had a particular artistic style as her own, but, according to the character and conditions of peoples and the needs of the various rites, she has admitted the artistic forms of every age, thus creating, down the centuries, an artistic treasure to be preserved with every care. The art of our own time and of all peoples and countries must also have freedom of expression in the Church, provided that it serves with due reverence and honor the needs of sacred buildings and sacred rites. In this way, it will be able to add its own voice to the admirable concento of glory which exalted men raised in past centuries to the Catholic faith".

This is the reason why these themes are complex and demand great respect, without schematism and without seeking ways and forms that are universal or immutable. God is infinite and eternal, but the ways we have of representing him are not infinite and eternal, because they depend on matter, techniques and culture, which refer to the richness of God but do not exhaust it, not even in a poetic or symbolic way.

If this were not so, God would become an "object" that we possess and that we delimit. If God is infinite, infinite will be the ways of referring to him, and some of them will be more adequate to the sensibility and taste of a people, in an epoch. To put God in an aesthetic scheme is tantamount to turning him into an idol. Moreover, it is necessary that Christian art be incarnated, just as the Word of God was incarnated, assuming a human form that used a way of dressing, of speaking, of manifesting himself, which was and is as significant for his contemporaries as it is for us.

Ambiguous terms

The question of sacred art, that is, of the relationship between God and human cultures, is also complicated by the fact that there is no clarity about the terms used. Sacred art is a very broad and somewhat ambiguous expression. Some scholars prefer to speak of liturgical art (and then it is necessary to specify which liturgy we are dealing with), of religious art (and here it is necessary to understand which religion we want to deal with, because even within Christianity there are different visions, from Orthodox to Catholic, passing through the different and specific visions of the Protestant churches). Art in the service of the Church, and of the churches indeed, reflects, and in a certain way amplifies, the existing differences, but it should also highlight the points in common.

Lucio Fontana and the "White Way of the Cross".

Having made this preamble, I will move on to the first artist I propose: Lucio Fontana (Rosario di Santa Fé, Argentina, February 19, 1899 - Comabbio, Italy, September 7, 1968) and his "White Way of the Cross".

Why do I propose Fontana? The reason is simple: he is an artist who experimented and innovated. Argentine by birth, he came from an Italian family of sculptors who worked for the funeral industry in Rosario: his father, originally from Varese, had married an Argentine actress, Lucia Bottini, also of Italian origin. Lucio studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Milan. He is a model student, very good in figurative art, but as soon as he graduates he will take completely different paths, with a search that he called "spatial".

Fontana breaks with tradition, in this he is very contemporary. The break with tradition is not really an element of absolute novelty because, especially in Western art of every era, artists have distanced themselves in an innovative way and in a way that breaks with the generation that preceded them. In contemporary art, the break is with classicism, with the so-called academic art, often returning to the "primitives". Fontana would become famous for the cuts on the canvas, which in his intention were a quest to go beyond, not an act of disfigurement of pictorial art, as some have understood.

The Stations of the Cross as a theme in Fontana

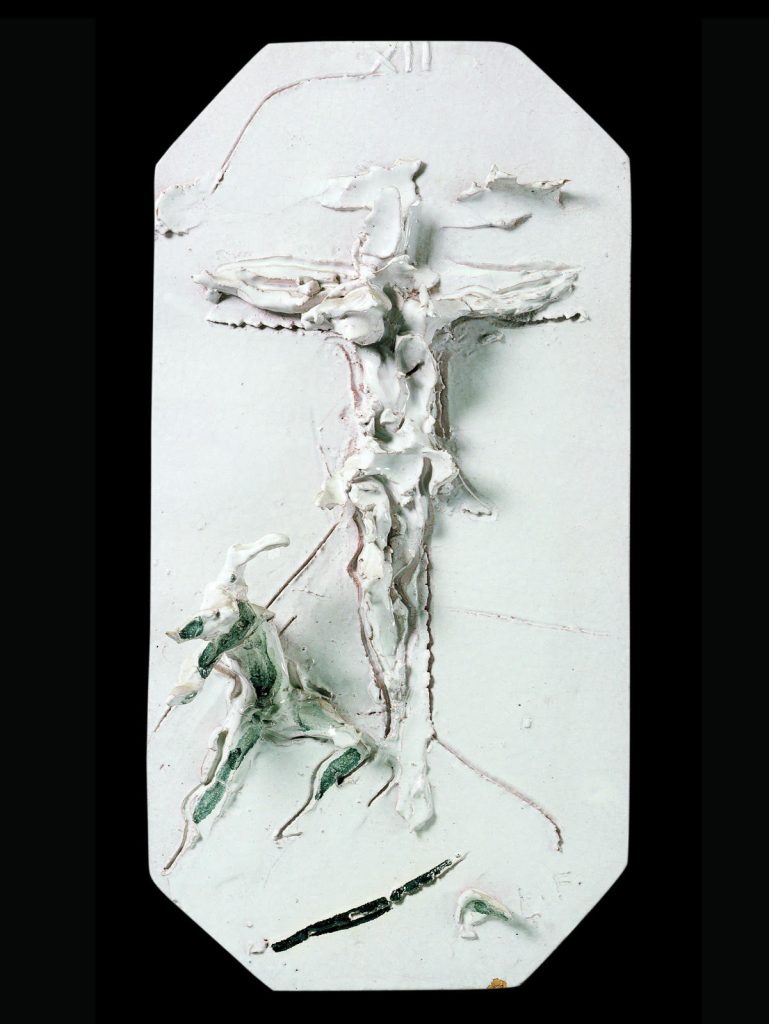

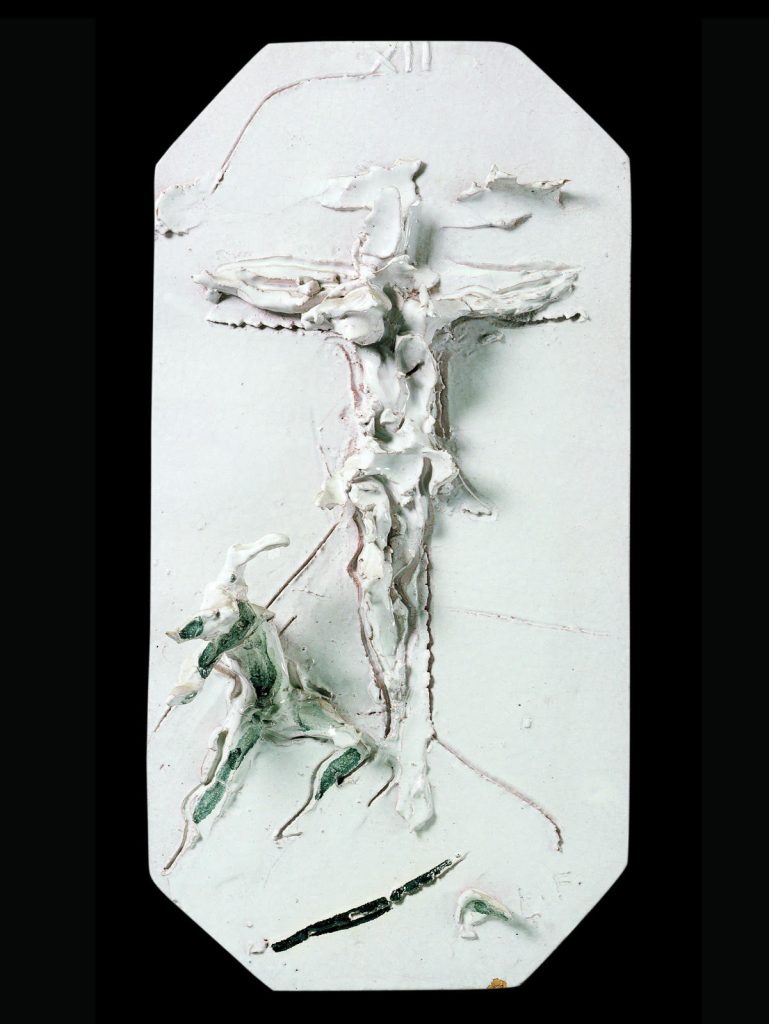

Fontana was interested in the theme of the Stations of the Cross, and in fact he would make three of them in a fairly short space of time: the three-dimensional, very colorful, glazed ceramic, dated 1947, which belongs to a private collector and which Fontana executed "without any commission" - as the Italian art critic Giovanni Testori wrote - "driven, therefore, by his own very private tension and need"; the white Stations of the Cross, to which we want to refer here, dated 1955-1956, and which is in the Diocesan Museum of Milan; and, finally, the terracotta one of 1956-1957, with 14 oval stations, currently in the church of San Fedele in Milan.

I find the white Stations of the Cross the most effective, with its octagonal stations - a clear reference to the resurrection and the eighth day - emerging from a homogeneous reflective surface, the white of the ceramic. The barely sketched figures, strongly dynamic, dramatic in their dazzling whiteness, are given even more force by the wise use of black and red. Fontana is a minimalist. He tries, with a quick gesture, to capture the essence. He says without exhausting, insinuates, postpones, urges a personal contemplation. The Way of the Cross is the story of Christ and, in a certain way, of every man. The figures emerge from matter, they are earth, they are dynamic, they move. And the artist's point of view also moves and, with it, the point of view of those who contemplate the works. Some scenes are at our visual height, others we can contemplate from above.

In this work, the artist moves the material in relief, but also uses engraving. The ceramic becomes something similar to a sketchbook. Great mastery of composition, but above all speed of execution and incisiveness. Obviously, in this case it is not a simple improvisation, because behind each scene there is much thought and reflection, which nevertheless takes shape quickly, to stimulate contemplation and personal prayer, with a freshness and drama that have - in my opinion - nothing to envy to other famous Stations of the Cross of Christian art.