I was born in St. Petersburg in 1994. In those years, in the most culturally "western" city of post-Soviet Russia, being "weird" was very common. My family was also "weird": we were fervent Protestants.

The community we frequented was a mixture of Evangelicals and Baptists. Every Sunday we had a meeting in a neighborhood library building. We sang, prayed, listened to sermons and talked with our peers, evangelized by American and English pastors.

Protestant liturgy

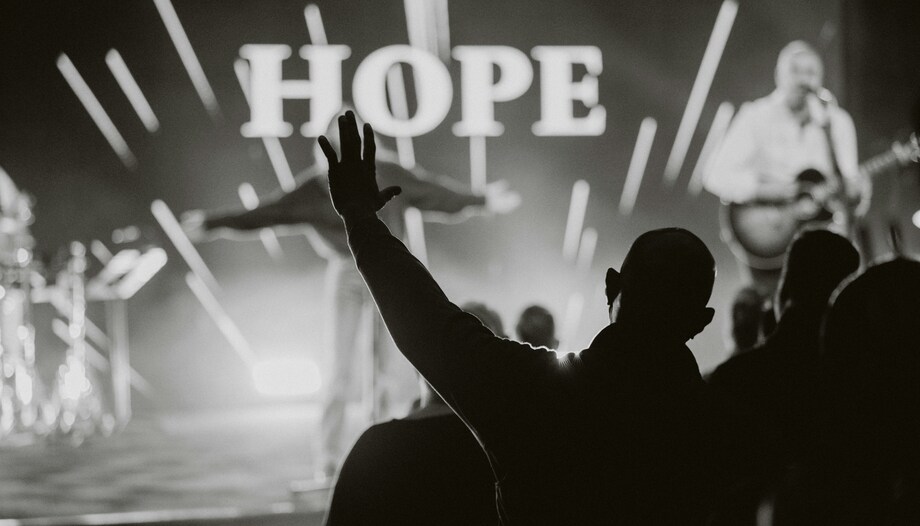

The "liturgy" of these meetings was quite simple: first, we hung large signs with the words "Jesus" and "God is faithful" on the walls of the rented assembly hall, then a musical group came on stage - it was their service to the community - with drums, bass, acoustic guitar, violin, flute and keys.

The lyrics of the songs were projected right there. The lyrics were simple, understandable for everyone and motivating, sometimes they even made us cry, either from joy or from feeling like forgiven sinners in the hands of God. They often played world hits of Protestant pop groups translated into Russian. Sometimes we clapped along with them.

Then came the meditation of the Word led by one of the pastors, the moment of "giving peace", - about 5-10 minutes a little uncomfortable, in which we asked ourselves how we were doing and if everything was going well -, followed by a symbolic remembrance of the Last Supper.

There were also retreats (retreats): weekends in cottages spent in silence, praying together, studying the Scriptures and many other activities. Thanks to this Protestant community many people began to read the Bible daily, to address Jesus in their own words and "not to be ashamed of the Gospel of Christ" (cf. Rom 1, 16).

Traditional" Christians

About the more "traditional" Christians, such as the Orthodox and Catholics, if mentioned at all, it was said that their ways of doing things were obsolete, did not respond to the needs of contemporary society and often preferred their archaic rituals to a living relationship with God.

A special comparison was made with the whole Orthodox tradition, the dominant Christian confession in Russia. They criticized the "idolatry" towards icons, long rites in an incomprehensible language (the Liturgy is celebrated in Church Slavonic), the strange clothing of the clergy and old women who scold you if you do not cross yourself when you enter the church or, if you are a woman, when you enter wearing pants or without covering your head. Most of these criticisms, besides not having much real foundation, are nothing more than isolated and punctual events, which have been taken to the extreme and have become stereotypes among people who have not spent a minute to be interested in the why of the things we Christians do.

Conversion to Catholicism

My family converted to Catholicism thanks to my father's intellectual restlessness when I was fourteen years old. My father became interested in early Christian history and one day he took us - my mother, my younger brother and me - to a nearby church. Besides not having to learn Bible verses by heart, being a recent convert from Protestantism, it is unnecessary to relearn how to pray; that same Jesus with whom you had spoken earlier in your personal prayer is in this box that Catholics call the Tabernacle. More than a conversion, it is an encounter.

From this encounter, all the "complexity" and "archaism" of the Liturgy - both Roman and Byzantine - began to seem to me a requirement of common sense. There, before the living Christ, one could not sing the same songs or do the same as in the Protestant community: everything I had done before, all the "modernity" and "clarity" of Protestant worship seemed inadequate. The presence of the living God demanded not "modernity", but "eternity"; not the "understanding" of language, but the "mystery", because God, being eternal, is something more than "modern", and being Mystery, is much more than one can understand.

The "temazos

I don't know what drives certain pastoral decisions, but I suppose that to someone who has encountered God in a Catholic temple, it is strange to see the Alpha and Omega hidden behind a sign - composed in "a current and understandable language" - of the pop genre. As if God cares more about fashions than people.

It seems that there are musical genres whose form is inseparable from the event to which they are dedicated. For example, singing "Cumpleaños feliz" or "Las Mañanitas" only makes sense in the context of the event for which they are intended. However, Mexicans would not think of changing their birthday song - either because it might be "difficult for others to understand" or because it is considered "old-fashioned". It is curious that something similar does not happen with music intended for events such as Mass, an event that has a much deeper meaning in the lives of Christians than a birthday.

I have been in Spain, the most Catholic country in Europe, for two years now, and I am confused by the eagerness of some people to turn the Liturgy into something that, in their opinion, reminds me of my Protestant childhood in a rented room of the neighborhood library: some signs, a stage, a backing entrance song, a sweet melismatics that touches the feelings, but does not help to order them; a "temazo" that says nice things, but whose genre condemns it to monopolize the limelight. "It's what people like. It attracts young people." That's what they used to say in my beloved Protestant community.

Linguist and translator, PhD in philology from the Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (Moscow).