The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity focused on the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. It highlighted the theological and ecclesial heritage of the historical experience of the Reformation in its country of origin and, at the same time, the good relations between Catholics and Lutherans today, fifty years after the beginning of ecumenical dialogue. The most accredited expression of the new climate took place last October 31 in the city of Lund, Sweden, during the ecumenical meeting between Pope Francis and the President of the Lutheran World Federation, Bishop Younan.

How was it possible, after centuries of contention between Catholics and Protestants, that representatives of both Churches together gave thanks to God for "the spiritual and theological gifts received by the Reformation," deploring the fact that Lutherans and Catholics had wounded the visible unity of the Church? Perhaps the phrase that explains it best is found in the Joint Declaration: "While the past cannot be changed, memory and the way of remembering can be transformed". This is that indispensable process of ecumenical dialogue called "purification of memory" or the search for a new way of understanding the discord that caused the separation.

The Second Vatican Council, by recognizing that divisions have occurred "sometimes not without responsibility on both sides," and that "those who are now born and nourished by the faith of Jesus Christ within these communities cannot be held responsible for the sin of separation" (Unitatis Redintegratio, 3), inaugurated the path of this profound purification of memory. A dispassionate look at the disputes of the sixteenth century revealed the true intentions of the Reformers and their opponents. When Luther published his theses against indulgences, he was an Augustinian monk with an intense spiritual life, though scrupulous and even tormented, certainly scandalized by how the salvation of souls was almost subordinated to a kind of commerce administered by churchmen. It was to be expected that his criticism would arouse a strong reaction. What could not have been foreseen was the religious, social and political revolt that followed and the division of the Church itself.

More than four centuries of conflict and mistrust can only be overcome by a profound conversion that will enable the Churches to distance themselves from errors and exaggerations. St. John Paul II suggested: "Only by adopting, without reservation, an attitude of purification through truth, can we find a common interpretation of the past and reach a new starting point for today's dialogue" (Message to Cardinal Willebrands, October 31, 1983).

Consequently, the ecumenical path requires a better understanding of the historical truth of events, a shared interpretation of what is right and wrong in persons and events and, on this basis, the willingness to move in a new direction. Such has been the path followed by Catholic-Lutheran dialogue over the past five decades, the results of which are recorded in the document "From Conflict to Communion" (2013) by the International Commission for Catholic-Lutheran Dialogue.

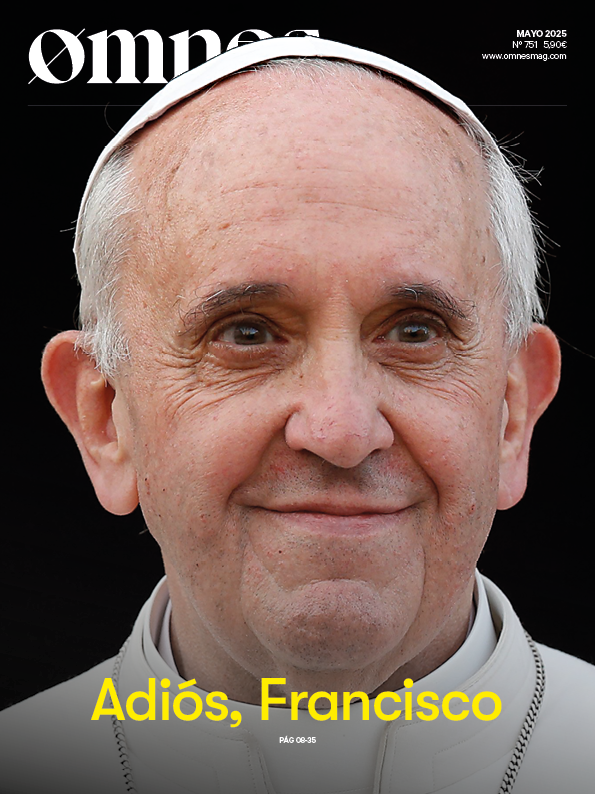

The historiography of the last century has led to a less polemical judgment of the figure of Luther and has contributed to the creation of a new climate of mutual understanding. This revision of the figure and work of Luther has been echoed in pronouncements of recent Popes, beginning with Paul VI. For example, in an interview on June 26, 2016, Pope Francesco said, "I believe that Martin Luther's intentions were not wrong: he was a reformer... The Church of the time was not exactly a model to imitate; there was corruption, worldliness, attachment to money and power. That is why he protested.

The Lund event has brought the ecumenical world to a clear awareness that the way in which the past influences the present can be changed. "The key is not to tell a different story, but to tell that story differently" (From Conflict to Communion, 16). And ecumenism "lived", and not only thought and discussed, is bearing positive fruits, which are a promise and a solid hope for the road still to be traveled.

In harmony with the recent Year of Mercy, the common commemoration of the Reformation in Lund emphasized how, in a society dominated by economics and efficiency, there is an urgent need to make the transcendence of the question of God understood. And the meaning of Lund is also this: that Christians, although still divided, can no longer remain incommunicado or in conflict when it comes to witnessing to the faith. The Pope recently emphasized this to the Council for Promoting Christian Unity: "My recent visit to Lund reminded me of the timeliness of that ecumenical principle formulated there by the Ecumenical Council of Churches in 1952, which recommends that Christians 'do all things together, except in those cases where the profound difficulties of their convictions require them to act separately' ".

Secretary of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of Christian Unity