I would like to dwell briefly on the story of two saints, unknown to most, but who really have much to say to the Church today. I am referring to the martyrs Pontianus and Hippolytus, whom we celebrate on August 13, with a very humble free memorial, which in the world of the liturgy is the minimal way of remembering someone.

We are in the third century, in the first decades of the year 200. Hippolytus was an extremely moralistic and rigorous presbyter who came into collision with the pope of the time, St. Zeferin. The reasons for the disagreements are not clear, partly of dogmatic origin on the nature of Christ (the councils that would clarify it had not yet been held) and partly on the possibility of readmitting into the community Christians who had abjured under torture (the so-called lapsi). Tension erupted when, upon the death of Zeferinus, St. Callixtus, a man of humble origin and deacon of the previous pontiff, was elected pope. Hippolytus did not accept the appointment and, elected by his followers, made himself pope, thus becoming the first antipope of Christianity.

On the death of Callixtus, Pontianus was elected, whom Hippolytus hastened not to recognize for the same reasons. The year 235 arrived and with it the coming to power of Maximinus the Thracian, an emperor opposed to Christianity who, as soon as he had the opportunity, condemned Pontianus to hard labor: ad metallathe mines of Sardinia. Pontian, moved by heroic humility, so as not to leave Rome without a bishop, resigned his office, thus enriching the century not only with the first "antipope" but also with the first "resigning" pope. Shortly thereafter, the emperor, unable to distinguish between popes and antipopes, condemned to the same punishment Hippolytus, who found Pontianus in chains. And here the miracle happened. Surprised by Pontian's humility, patience and meekness, Hippolytus converted and acknowledged his error, thus reconciling the schism. Both died as a result of the ill-treatment and inhuman conditions they suffered, and since then the Church celebrates them together as saints and martyrs.

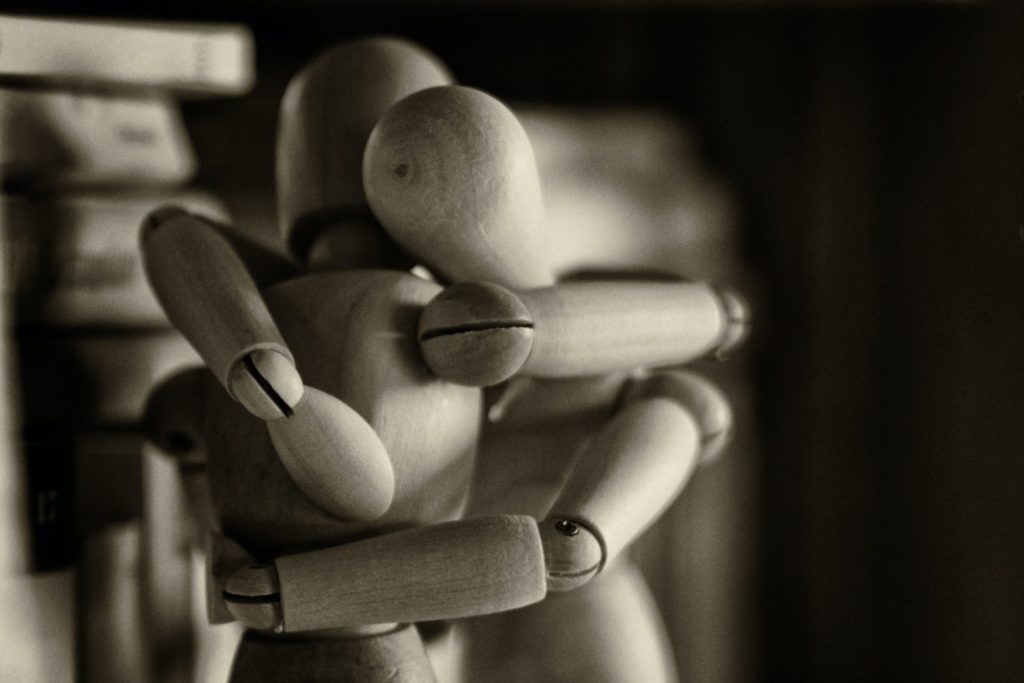

The past of the saints can provide us with many lessons. Too much rigor and too much certainty in believing that we know, even if dictated by the most perfect good faith, can divide rather than unite and can weaken the Church rather than strengthen it. Above all, in Christianity, weakness is more convincing than strength. Pontian is an instrument of grace not because he clings to power, but because he renounces it, putting into practice Christ's teaching that he who would truly rule must be a servant of all. The last lesson is perhaps the most moving. Hippolytus, who in the name of truth had made himself an enemy of Pontianus, finds the good of the other within a path of pain that unites them both. Only through the cross is it possible to see who each is. Only by walking together in that field hospital which is the Church in true life, is it possible to know each other, to recognize each other and to help each other to build that Good which is the patrimony and desire of every human heart.