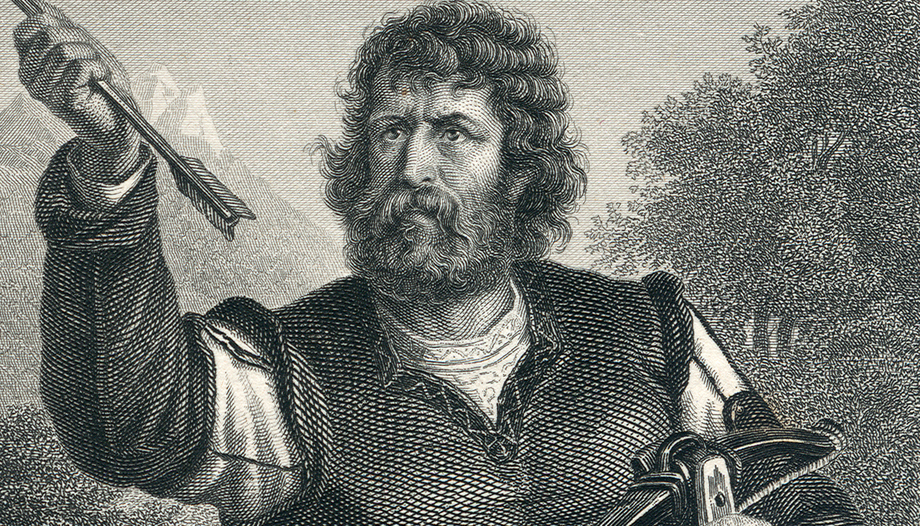

Over the centuries, the figure of William Tell has embodied the ideals of the struggle for freedom and independence of Switzerland first and later those of paternal love and the struggle for justice.

According to legend, Tell was born in the canton of Uri and married a daughter of Furst of Altinghansen, who together with Arnold of Melchthal and Werner of Stauffacher had sworn on September 7, 1307 in Gruttli to free his homeland from the Austrian yoke.

The Habsburgs pretended to exercise sovereign rights over the Waldstetten and Herman Gessler of Brunoch, "dance" of those cantons on behalf of Emperor Albert, wanted to impose his authority with acts of real tyranny that irritated those rough mountain people.

He wanted to force all Swiss to unveil themselves in front of a hat, placed at the top of a pole on the Altdorf square, which, according to the conjecture of the historian Müller, must have been the ducal hat.

Tell, indignant, came down from the mountain to the square of Altdorf, wearing the characteristic costume of the shepherds of the Four Cantons, covered his head with a hood and wearing sandals with wooden soles reinforced with soles and bare legs. And he refused to submit to this humiliation.

The William Tell test

The "dance" ordered him to stop. And, knowing his skill in the handling of the crossbow, he threatened him with death if he did not succeed in knocking down with the arrow, from 120 steps away, an apple placed on the head of the youngest of Tell's sons. From this terrible ordeal, which legend has it that took place on November 18, 1307, the skillful crossbowman emerged victorious. When Gessler noticed that Tell was carrying a second hidden arrow, he asked him for what purpose he was carrying it. "It was for you, if I had had the misfortune to kill my son," was the reply. Gessler, incensed, ordered him to be put in chains, and to prevent his compatriots from freeing him, he wanted to lead him himself across Lake Lucerne to the castle of Kussmacht.

In the middle of the lake they were surprised by a violent storm, caused by an impetuous south wind, very frequent in that region, and, faced with the danger of capsizing and drowning, he ordered the prisoner's chains to be removed and to take the helm, for he was also a skilled navigator.

Tell managed to board next to a platform, known since then by the name of "Tell's Leap," located not far from Schwitz. He quickly jumped ashore and, giving the boat a push with his foot, left it again at the mercy of the waves. Nevertheless, Gessler managed to gain the shore and continued his march towards Kussnacht. But Tell went ahead and, stationing himself in a suitable place, waited for the tyrant to pass and mortally wounded him with an arrow.

This was the beginning of an uprising against Austria. Tell took part in the battle of Morgaten (1315) and, after a quiet life, died in Bingen in 1354, being a recipient of the Church.

History and legend

The story has been passed down through Swiss tradition. Contemporary chronicles of the Swiss revolution of 1307 do not mention Tell. But at the end of the 15th century Swiss historians began to speak of the hero, giving various versions of the legend.

Gessler's name does not appear in the complete list of the Altdorf "dances". None of them were killed after 1300. On the other hand, a governor of Kussnacht is found to have been killed when he jumped to earth by an arrow shot by a peasant whom he had molested in 1296, the event taking place on the shores of Lake Lowertz and not on Lake Schwitz. Probably the legend has taken as its origin this historical fact, prelude of the insurrection of 1307.

Tell is not a name, but a nickname; it comes, like the German word "tal", from the old German "tallen", to speak, not to know how to be silent, and means exalted madman, having been applied in contemporary chronicles to the uprising of the three conspirators of Gruttli, considered, before the triumph, mad and reckless.

Frendenberger wrote in 1760 a book entitled "William Tell, Danish Fable". The legend, in fact, is found in the Scandinavian countries before the Swiss story-legend. It is quoted, among others, by the Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus, in his "Danish History", written at the end of the 10th century, attributing it to a Gothic soldier named Tocho or Taeck.

It is probable that emigrants from the north, settled in Switzerland, imported the legend and even the name. Similar legends exist in Iceland, Holstein, on the Rhine and in England (William of Cloudesley).

In honor of William Tell

The plausible thing is, as it happens in analogous cases, that all these legends have been accumulated to a real personage, since the construction of chapels in honor of Tell, only thirty years after the date in which his death is situated, proves in an indisputable way that the legends were supported in a real fact. These chapels are still the object of veneration in Switzerland. One of them stands on the shores of Lake Schwitz, on the same platform on which the hero jumped ashore. It is said that, when it was built in 1384, its inauguration took place in the presence of 114 people who had known Tell personally.

Rossini wrote an opera on the theme and Schiller a drama. This, in 1804, is the last one he composed and is considered his masterpiece. A totally harmonious work," says Menéndez y Pelayo in his work Ideas Estéticas, "and preferred by many to the rest of the poet, is William Tell, in which one certainly does not admire the grandeur of Wallenstein or the pathos of Mary Stuart, but a perfect harmony between the action and the scenery, a no less perfect interpenetration of the individual drama and of the drama which we might call epic or of transcendental interest, and a torrent of lyrical poetry, as fresh, transparent and clean as the water that flows from the very Alpine peaks".