"In the years 46 to 47, we were given to live exceptional moments in an ecclesial climate of rediscovered freedom".Congar recalls in his long interview with Jean Puyo (Le Centurion, Paris 1975, chapter 4). The joy of victory and peace in France was mixed with the desire to build a new world and a renewed and missionary Church.

He was already deeply involved in the ecumenical movement. Between 1932 and 1965, every year, including some of those of captivity, he preached, wherever he was called, the Octave of Christian Unity, which had given rise to his pioneering book Disunited Christians (1937).

To read more

The book had aroused some reticence, now renewed with the second edition.

"At the end of the summer of 1947, we can place the first manifestations of concern from Rome. We began to receive a series of warnings, then threats in relation to the worker-priests. I was not granted the permissions I asked for (I never failed to request permissions from my superiors when necessary)". He was unable to attend the ecumenical preparatory meetings for the creation of the Ecumenical Council of Churches in Geneva (1948).

Understanding the era

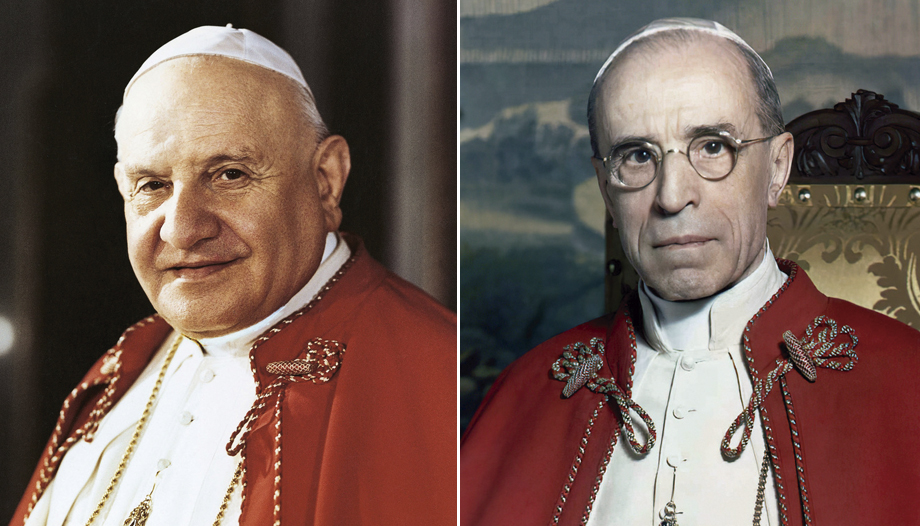

Roncalli, later John XXIII (1944-1953), was then Nuncio to France. And there were difficulties of different nature and importance. We have already mentioned some of them. On the one hand, there was the susceptibility of a rather wounded traditional Catholic sector and the discomfort and incomprehension of the theology that we call manualistic in the face of the new theological currents. Both of these promoted suspicions and denunciations in Rome. On the other hand, the Holy See saw the birth of the ecumenical movement and did not want it to get out of hand. And, above all, it was moved and alerted by historical events.

It has been said that Pius XII was obsessed by communism. This is a gross ignorance of history. Between 1945 and 1948, with a collection of violence and electoral frauds, the USSR imposed communist regimes in all the occupied territories: East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria, as well as directly incorporating Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and a part of Poland. The local communists took over Yugoslavia and Albania. In 1949, Mao took over China. In 1954, the communists took over the northern half of Vietnam and began the invasion of the south, until taking Saigon in 1975.

In those years, millions of Catholics and hundreds of dioceses were subjected to communist repression and trickery. Every day sad news arrived in Rome, some of them terrible. A martyrial Church had been created, a "Church of silence". So much silence that many do not remember it when they naively describe this era.

And in France, Italy and Austria there was a tremendous communist political, propagandistic and cultural pressure, which affected everything, and the Church as well. And that covered up what was happening on the other side. Stephen Koch is worth reading, The end of innocenceHow could Pius XII, in the 1950s, not be very concerned about communism? Only when those regimes were firmly established was Paul VI able to attempt a dialogue of good will that did not meet with good will. And today it is still being attempted with China, Vietnam... Cuba... Venezuela.

Congar's bad years

In the face of this, other issues could not have seemed very serious to Pius XII. Pressed by the complaints and denunciations before the "nouvelle Théologie", composed the encyclical Humani generis (1950), describing generically some possible deviations, but did not want to name or condemn anyone. It contained a line discouraging false irenism. Some disciplinary measures were taken, some books were put on the index (Chenu) and, above all, the experiment of the worker priests was suspended (1953), which with that communist pressure and manipulation could not go well, even if it really had an evangelical inspiration.

In 1954, the Holy See had the three Dominican provincials of France changed and demanded the removal of four professors, including Chenu and Congar, from their posts and from teaching. In fact, Congar had hardly had any connection with the movement, except for occasional writings. And, perhaps for that reason, it was not clear what could be objected to him.

At the end of 1954 he was urgently summoned to Rome for an interview with the Holy Office. But six months passed without an interview. From different sides he was advised to correct Disunited Christiansbut never knew what to correct. "Change something."The general of the Dominicans suggested to him at some point. And the same happened with True and false reform in the Church, which he had published in 1950. Also, by osmosis, another pioneering essay of his encountered reticence: Milestones for a theology of the laity (1953), which has been very important in the history of the subject.

To read more

After returning from Rome in 1954, he was sent to Jerusalem for a few months and then to Cambridge, where he felt very isolated. In 1956, he was welcomed by the Bishop of Strasbourg, who knew him well. There he carried out normal pastoral work, with limitations on teaching and publication censorship. It was a very bad ten years for him (1946-1956), because of that feeling of rejection without information, as can be seen in his Diary of a theologianwritten live. He remembers them with more distance and restraint in his dialogue with Puyo. But he also wrote a great deal: in 1960, a powerful two-volume essay appeared, on Tradition and traditionsin its theological and historical aspect. Tradition, in reality, is nothing other than the very life of the Church in history, animated by the Holy Spirit.

And then came the Council

Upon the death of Pius XII (1958), the former nuncio Roncalli was elected Pope and convoked the Council. In 1961, he appointed Congar as consultant to the Preparatory Commission. It was a rehabilitation. At the beginning, it was a matter of attending sessions with many others. But since March 1963, incorporated into the Central Commission, he played a very active role in the inspiration, drafting and correction of many texts.

In its overall presentation Listening to Cardinal Congar (Edibesa, Madrid 1994), the Dominican theologian Juan Bosch includes points written directly by Congar, such as numbers 9, 13, 16 and 17 of chapter II of Lumen Gentiumand part of chapter 1 of Presbyterorum ordinis or the first chapter of the Decree Ad Genteson evangelization. He also worked a lot on Gaudium et spesin Unitatis redintegratio (on ecumenism) and Dignitatis humanae (on religious freedom).

The great themes of the Council were its themes. He moved to advance them: to describe the Church as Mystery and as the People of God; to better understand her communion, a reflection of the communion of Persons of the Trinity, the basis of the communion of the College of Bishops and of the particular Churches and the horizon of ecumenism; to deepen the "priestly" mission of the laity in the world, elevating temporal tasks to God. Moreover, the ecumenical commitment, as soon as it was presented to the Fathers, won their hearts and changed the attitude of the Catholic Church to face the historical divisions. It was a great joy.

During those years, he regularly wrote chronicles of the Council for magazines, which he later collected in annual books (The Council, day after day): and he also kept a detailed personal diary, which is a primary source for the history of the Council (Mon journal du Concile2 volumes). And he had many dealings with the French Jesuits De Lubac and Daniélou, and the theologians of Louvain, Philips, Thils and Moeller. He also knew Bishop Wojtyla. He recalls that, when he was speaking, during the work of writing Gaudiun et spesHe was impressive for his poise and conviction.

Years of work

The Council turned out to be an exhausting work, since the commissions often worked at night in order to present the corrected texts the next day. But he was a hard worker. He usually dedicated 10 hours to writing, for many years. This explains the extent of his production.

In 1964, he collected a number of articles on ecumenism in Christians in dialogueHe also wrote a very interesting and lengthy memoir about his work and ecumenical vocation.

Composes for the theological course Mysterium salutis (1969), a very extensive writing on the four notes of the Church, with its historical foundation: one, holy catholic and apostolic. And he prepares two extensive volumes on the Church for the history of the dogmas of Schmaus. It is a major work and also pioneering, even if he was not able to collect and synthesize everything.

Multiple tasks

Since the end of the Council, he has been invited everywhere to give lectures and courses. And he feels it as a duty. If you can transmit, you have to transmit. It was his service to the Church. But he began to develop a sclerosis that had already manifested itself in his youth.

In 1967, during a very intense trip through several American countries, where he sometimes has to use a cart, he suffers a collapse in Chile. He needed months of recovery. From then on, his limitations grew and his mobility became more complicated, but he continued to work and traveled as much as he could. As he needs more physical care, in 1968 he moves from Strasbourg to Le Saulchoir, near Paris.

From 1969 to 1986, he was a member of the International Theological Commission and participated in its work. He is a member of the editorial staff of the magazine CommunioHe remained there in spite of the problems he perceived (he considered Küng a good theologian, but rather a Protestant). He soon notices, like other responsible theologians and friends, what is not going well in the post-conciliar period. And he calls for responsibility, both in theology: Situation and tasks of theology today (1967), as well as on the life of the Church: Between storms. Today's Church faces its future (1969). He also analyzes the schism of Bishop Léfebvre: The crisis in the Church and Mgr Léfebvre.

He is concerned about the misinterpretation of the Council, the theological drifts and the trivialization of the Liturgy. Although he maintains a confident tone in the fruits of the Council. He places himself in the tradition: "I don't really like the title of conservative, but I hope to be a man of tradition.". In that living tradition to which he has devoted so much attention.

Last years

With a growing limitation, which even paralyzed his fingers, he continued to work. It is beautiful that, in the twilight of his life, all his work on the Church leads him to write about the Holy Spirit. With all the major themes outlined, he composed three volumes (1979-1980) which were later to be collected into one, The Holy Spirit. Without being a complete systematic treatise, it is a broad overview of the main points: its role in the Trinity, in the Church and in the interior of each believer. With that characteristic style of his, very loose, which combines thematic highlights with historical developments.

The disease progresses. A few years earlier he had obtained a disability pension, arguing that the illness was due to the hardships of his long imprisonment during the war. It was granted. With the same title, in 1985, when he needed specialized care, he was admitted to the great hospital founded by Napoleon for the war wounded: The Invalidesfrom Paris. He will spend his last years there, dictating because he can no longer write, answering mail, receiving visitors.

In 1987 he gave another long autobiographical interview, very interesting, although shorter than the one with Puyo, to Bernard Lauret, entitled Entretiens d'automne (Fall Conversations). That same year he wrote an introduction to the Encyclical Redemptoris Materof John Paul II. And, as if it were a symbol of his life, his latest magazine article, on Romanity and catholicity. History of the changing conjunction of two dimensions of the Church..

In 1994, John Paul II named him a cardinal; he died the following year, 1995.

Other considerations

Congar's work is so extensive that it is not even possible to collect the significant titles. Some of the most important ones have been pointed out. The bibliographical note provided by Juan Bosch in his overview lists 1,706 works. Among them is, for example, his participation in the great dictionary Catholicismeto which he contributed hundreds of voices. And a curious collaboration with the Spanish magazine Medical Tribune (1969-1975).

The interviews with Puyo and Lauret are very interesting to see him reasoning live. His three diaries on the first war (1914-1918), his hard times (Diary of a theologian) and his participation in the Council are also well constructed. Fouilloux's biography is well constructed, and there are already a large number of theses and essays on his work. There is no doubt that he has left a very important theological heritage.