The Debate on Christian Philosophy (1931)

The Debate on Christian Philosophy (1931) The stages of Joseph Ratzinger (II). Prefect (1982-2005)

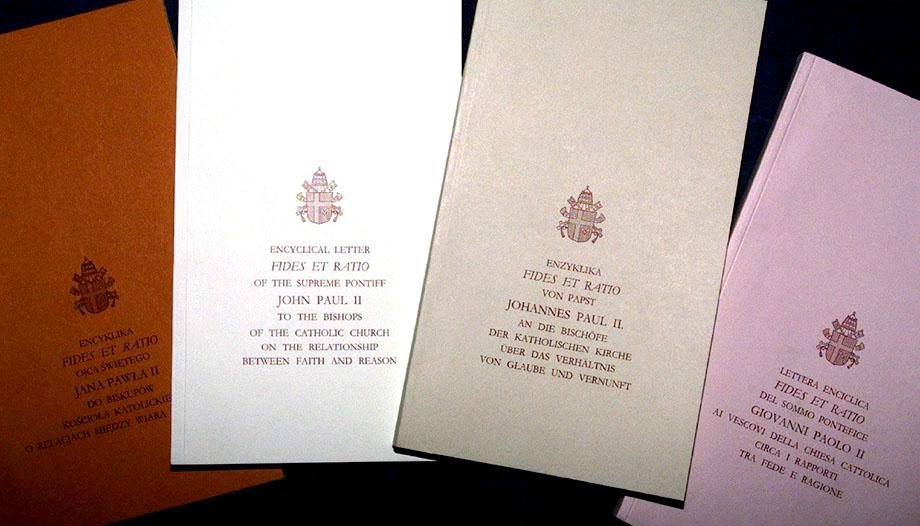

The stages of Joseph Ratzinger (II). Prefect (1982-2005)When, twenty-five years ago today, John Paul II published Fides et ratioThe end of the century was near.

The Pope was well aware of his mission: to guide Peter's ship into the ocean of the third Christian millennium. It is therefore not insignificant that, after an already long pontificate, he decided to address the question of "faith and reason" in an encyclical.

It is not an exclusive problem of our time, but each era must deal with it in its own way, so that Fides et ratio provided keys to do so in our own.

Faith

When we speak of "faith and reason" we do not mean that in man there are two completely different types of functions. It is not that believing and reasoning are as different as listening to music and riding a bicycle. Rather, they are as different as riding a bicycle and riding a scooter: both operations are done with the limbs, not with the ears. Well, both believing and reasoning are done with only one human faculty: reason.

When Christians speak of faith we think of something that only rational beings can do. Believing is in itself something rational. In general, to believe is to know something by learning it from someone else: it is, therefore, a kind of knowledge.

Just as what we learn for ourselves, what we believe we must understand and our intelligence demands that we strive to understand it better and better. The fact that through Christian faith we believe God under the impulse of the Holy Spirit does not make it something totally different from our human belief, it only elevates it -which is no small thing-.

The encyclical recalled the rational character of faith and the natural affinity between believing and reasoning. It should be obvious to us if we think that, wherever Christians have proclaimed the Gospel, they have been busy gathering and disseminating all kinds of knowledge, founding colleges and universities, writing myriads of books....

The reason

Despite such obvious facts, we hear the refrain of an alleged confrontation between faith and science. Even some Christians have integrated such a discourse and are afraid to ask too many questions, lest the truth crumble their faith. For these reasons, it never hurts to remember that faith is the friend of reason.

The friendship between reason and faith can be seen in the fact that faith, which is received in the human being's reason, is called to be better known and deepened. The fundamental thing is to understand what is announced by the one who teaches us the faith, what is to be believed, but to dwell with the intelligence on it also supposes a growth in faith.

Vice versa, faith also impels us to know better not only Christ and the Gospel, but also other things. We should not be surprised by the great interest that so many Christians have cultivated in studying all kinds of subjects, because in nature and in the products of human ingenuity the benign intervention of the Creator shines forth.

I am taking over here one of the most well-known ideas of Fides et ratioThe Christian faith invites us to reason, both to reason what we believe and to immerse ourselves in all kinds of knowledge. Christian faith invites us to reason, both to reason what we believe and to immerse ourselves in all kinds of knowledge; likewise, the more we delve into the truth in all the facets that various human knowledge reveals to us, the more we are given opportunities to deepen our Christian faith. Thus, both types of exploration are mutually beneficial.

Faith and reason in the pontificate of Benedict XVI

Contemplating the life of the Church from 1998 to the present, the presence of the encyclical's message can be recognized. The pontificate of Benedict XVI (2005-2013) was marked by the purpose of showing contemporary man, postmodern man, that believing is reasonable, is deeply human.

The Pope was particularly sensitive to an idea still present among us: for many people "truth" is an aggressive, violent concept. To say that one has the truth and wants to transmit it to another is perceived as a desire to dominate one's neighbor.

Truth is thus represented as a sort of artifact over which men quarrel among themselves and even as a stone that some throw at others. Postmodern man believes it necessary to abandon truth for the sake of peace. He sacrifices truth on the altar of concord.

Fides et ratio already insisted that, in our times, it is part of the Church's mission to reclaim the rights of reason: it is possible and urgent to know the truth. Similarly, Benedict XVI refused to abandon the postmodernists in their voluntary fasting from truth. Human beings live on truth as trees live on sunlight and water: without it, we wither. Hence Benedict's effort to show the gentle character of truth.

In concrete terms, Christian truth, according to him, takes the form of an encounter. Encountering someone is not like stumbling over the stone that someone has just thrown at his rival; especially if we meet someone who loves us and, effectively seeking our good, arouses our correspondence. However, the encounter means a clash with reality. It is not the same to meet with one person as with another. It is not up to us what the person we meet is like; we do not decide, nor is it the product of our fantasy.

Moreover, the encounter forces us to decide, there is no way to remain neutral. Not to react is already to take sides: the Levite who passes by the wounded man does no less use his freedom than the Good Samaritan.

Well, faith can be seen as an encounter because to meet Christ (in the Church) is to meet someone who comes to love us. For this very reason, the believer cannot do without the truth: Christ is as he is, he has loved us by giving his life and not in any other way.

Authentic love means entering into a relationship with a real person, not with the idea that one has made of him or her. An encounter forces us to yield to reality. We do not invent Christ, we do not decide who he is, it is simply he who breaks into our life.

Now, a Christian does not appreciate this encounter as if he had been crushed by the truth, as if a fatality were hovering over him, but as a liberation.

The truth of Christ comes to give meaning to the whole of life, since it allows him to understand what is the fundamental meaning of his life and, therefore, of everything that surrounds him. It is not a truth that excludes the search for other truths; it is not that the Christian discovers on the spot all the secrets of the universe that are explored by the sciences. It does, however, provide a sure knowledge of what is most important.

This truth cannot be perceived as a destructive steamroller because it is the revelation of an authentic love. That is to say, a love that does real good to man. In this way, such a truth cannot be seen as something threatening or terrible.

On the other hand, it introduces the human being in a context of friendship: God has behaved as man's friend and has shown him that, although he loves each person in a particular way, there is no one whom he does not love. Therefore, such a truth, by its very nature, cannot become a stone to be thrown at anyone.

It does not create adversaries but brothers and sisters. On the contrary, communicating it, far from seeking to dominate others, will be a communication developed in the context of love, which is received in order to be given. Giving the Gospel is an act of love. There is no room for haughtiness in giving that which is not at one's disposal, for one only retains it in order to give it.

Faith and reason in Francis

After the pontificate of Benedict XVI, Francis also continued these teachings, first of all by publishing ten years ago the encyclical Lumen fidei, largely written by his immediate predecessor. Likewise, in his more personal teaching we can find the development of these ideas in his warnings about "gnosticism," a message already present in Evangelii gaudium (2013) but expanded in Gaudete et exultate (2018). Gnosticism is the name given to an ancient heresy of the early Christian centuries, and the term has been reused to denote certain more recent esoteric movements.

By "gnosticism", the Pope refers rather to a sickness in the life of the believer: turning Christian teaching into one of those boulders that some people throw at others. In the postmodern world that has renounced truth, some have turned "rational" discourse into just that, a tool of domination of other people. They do this deliberately because they believe that, in the absence of truth, the crucial thing is to win.

Francis denounces the risk of the Christian to make use of such evil tricks. This would mean extracting the truth of the Gospel from the friendly context in which it appears to us and in which we have to communicate it. Not even the truth of the moral misery of others is a pretext for our indifference or for adopting airs of superiority. In fact, the truth that we all discover in Christ is also liberating good news for the miserable, even for those whose lives leave much to be desired.

These twenty-five years of Fides et ratio have been very fruitful, and among theologians and intellectuals, St. John Paul II's commitment to reason has received much applause. Perhaps this feast day is a good opportunity to examine how it has permeated the daily life of the Church.

In the face of a widespread ignorance of the most elementary truths of faith, every Christian should feel compelled to make known the beautiful message he or she has received. The anniversary should also be an impulse to promote formation.

The wonderful technological tools shaping our landscape in 2023 have certainly provided us with more information, but are we now more educated? Certainly, there is no lack of reason for hope if there are many people like you, gentle reader, who have chosen to spend these minutes remembering Fides et ratioinstead of using them to roam the web in search of other more sensationalist readings.

Assistant Professor, Faculty of Philosophy, San Daámaso Ecclesiastical University