The Church has a handful of saints who have been great philosophers - Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas, Saint Anselm, Saint Bonaventure or Saint Albert the Great - so it is striking that the patron saint of philosophers is precisely a woman, Saint Catherine of Alexandria. Now, what merits did this 18-year-old girl have to be proclaimed patron saint of so many great thinkers? What great intelligence did she possess?

The story of St. Catherine of Alexandria

Hagiography first mentions Catherine of Alexandria between the 6th and 8th centuries, a rather late documentation considering that it explains that the martyr died in Egypt at the beginning of the 4th century.

The various documentation on the history of the saint culminated in the "Golden Legend"The book of the Archbishop of Genoa, Santiago de la Voragine, tells us that Catherine was a Christian noblewoman, daughter of King Costo of Alexandria, a young woman educated in the liberal arts, of great beauty and virtue. Catherine was eighteen years old when the emperor Maxentius (or Maximinus), who had arrived in Alexandria, ordered pagan sacrifices to be made on the occasion of his visit. Catherine refused and, entering the temple, tried to convince the emperor with an impeccable rhetoric.

The emperor, overwhelmed by her eloquence, sent for wise men from all over the Empire to refute the young woman's arguments. These wise men were converted to Christianity by Catherine and burned alive for it. Catherine was flogged and imprisoned, condemned to starve to death. But two angels accompanied her in her captivity, healing the marks of the scourging, and a dove brought her food daily. During her imprisonment, she managed to convert the emperor's wife, his general Porphyry and two hundred other soldiers.

When the emperor arrived again, he had Catherine tortured with a machine composed of cogwheels that, when touching the body of the young woman, jumped into a thousand pieces, killing four thousand pagans who were watching the condemnation. The empress, reproaching her husband for the cruelty of his acts and recognizing her conversion, was also beheaded, as well as general Porphyry and his converted soldiers.

Finally, the emperor had the young woman beheaded after Catherine refused his marriage proposal. From her body did not come out blood, but milk.

Several centuries of ignorance of the saint even cast doubt on her existence; nevertheless, as a didactic example of Christian life, St. Catherine holds the patronage of numerous offices, given her extreme erudition, and is considered an intercessor in the face of problems of all kinds.

– Supernatural Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius, of the fourth century, speaks of an Alexandrian woman who confronted the emperor (it is not clear whether it was Maxentius or Maximinus). It is also considered that the story of Saint Catherine could be inspired by and be a counterpoint to that of Hypatia (died in 415), an Egyptian philosopher of great erudition, of pagan religion, supposedly murdered by a mob of Christians in moments of great political and religious tension in the area. Other sources that speak of the saint are the Passio (6th-7th centuries) or the Greek menogolio of Emperor Basil, where she is represented with her attributes for the first time. All of these documentary sources would culminate in the Golden Legend.

Be that as it may, it seems that from the 8th century the veneration of Saint Catherine was common among the Christians of Egypt, since it was believed that she was buried on Sinai. The relics of the saint were found on that mountain in the ninth century, where, according to tradition, they had been transported by angels; the oldest representations come from Byzantium and the end of the tenth century (illustration from the Menologio of Basil), either as an isolated figure, as a biographical cycle or with specific narrative scenes.

Study of the iconographic type of the martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria

The first images of the saint to appear in the West date back to the 12th century, when her cult was extended by the Crusaders, shortly before Santiago de la Vorágine recorded the story of Catherine's life in his Golden Legend.

From the 14th century onwards, there was a notable increase in the number of representations and a diversification of themes. Not only did he appear in isolation with the traditional attributes, such as the cogwheel of his torture, the palm as a symbol of martyrdom, the various signs of erudition (such as books, mathematical tools or a terrestrial sphere), the crown as a sign of noble origin or crushing the emperor's head; but new themes such as mystical betrothal spread. The idea of life consecrated to God as a form of marriage is recurrent from the 14th century onwards. Thus, St. Catherine of SienaSt. Catherine of Alexandria, St. Teresa of Jesus, St. John of the Cross, make reference in their writings (or we read it in other people's writings after their death) to a similar relationship of surrender. In fact, there is no episode referring to this in the preserved documentation of St. Catherine of Alexandria; not even Santiago de la Voragine relates such a situation, and only indicates what God said to the saint moments before her beheading. "Come my beloved, come my wife, come!". Other recurring themes are that of the debate with the emperor's philosophers, her martyrdom or her conversion.

It is worth mentioning the similarities found between this saint and the aforementioned Saint Catherine of Siena: both are attributed with great erudition (not in vain Saint Catherine of Siena is a Doctor of the Church), a debate against wise men of the time or the episode of the mystical betrothal, in addition to her own first name. It is not unreasonable to think that there is a certain relationship between the life of the saint of the 14th century (better documented) and the evolution in the iconography of St. Catherine of Alexandria.

It has already been mentioned that the artistic representation of Saint Catherine of Alexandria has been very common in Christian iconography since the Middle Ages. The 16th century left rich and varied samples of the iconography of the saint in all its variants. Very well known is the painting by Caravaggio (1598) showing Saint Catherine with her most characteristic attributes: the palm, the wheel and the dagger.

Among the mystical betrothal, it is common to find representations where the saint, kneeling before the child Jesus, kisses his hand or receives a ring as a sign of alliance. The typical attributes usually appear as well. An example is the oil painting by Alonso Sánchez Coello (1578) in which the saint can be seen with the covenant on her finger.

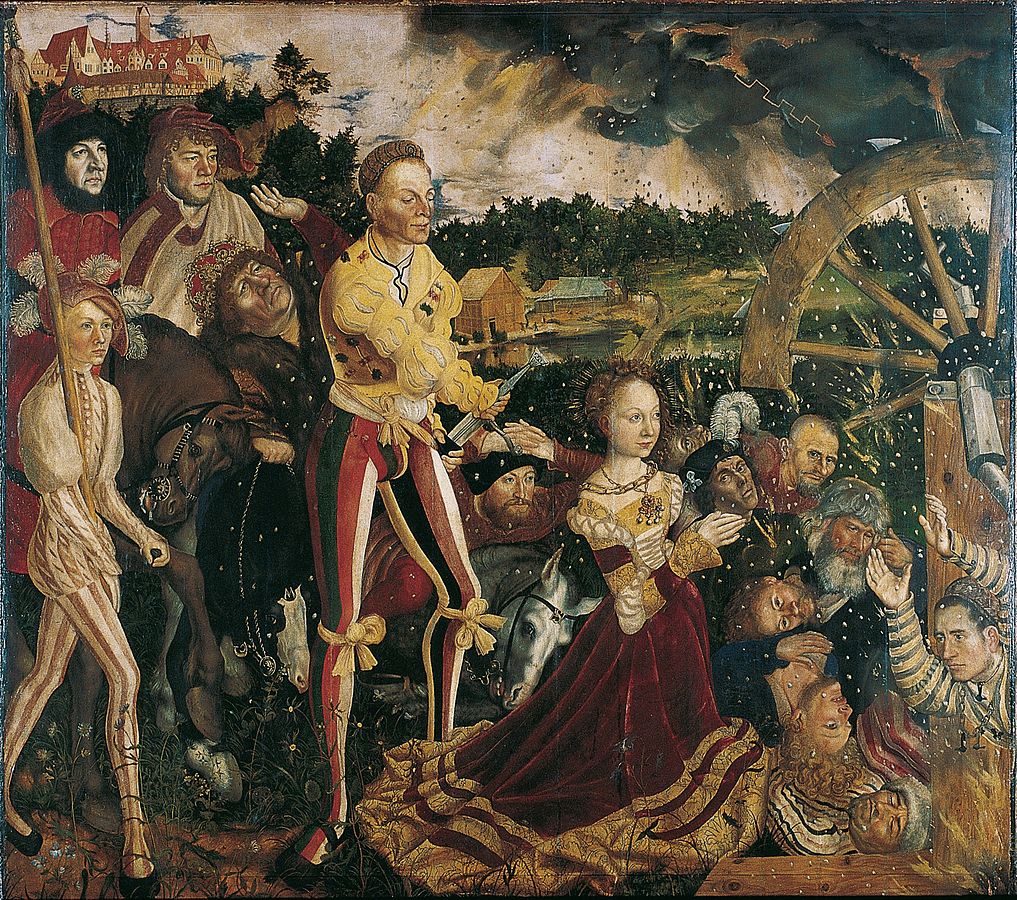

A painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1506) shows the moment when the torture wheel breaks and kills the pagans around the saint contemplating the spectacle.

There is a rich variety of representations of St. Catherine of Alexandria throughout Europe, where her figure is venerated in many places. She is considered a saint by the Catholic, Coptic, Orthodox and Anglican Churches.

BIBLIOGRAPHY .

-De la Vorágine, Santiago, THE GOLDEN LEGEND. VOLUME 2. Alianza Forma, Madrid, 1989.

-Monreal y Tejada, Luis. ICONOGRAPHY OF CHRISTIANITY. El acantilado, Barcelona, 2000.

-Record, André. THE WAYS OF CREATION IN CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY. Alianza Forma, Madrid, 1991.

-Franco Llopis, B.; Molina Martín, Á.; Vigara Zafra, J.A. IMAGES FROM THE CLASSICAL AND CHRISTIAN TRADITION. Ramón Areces, Madrid, 2018.

Professor of Art History.