Translation of the article into English

Near Seville there is an old stately mansion in whose garden is preserved an unusual cemetery for dogs.

I visited it a few days ago and found that those responsible for those extravagant tombs did not make them out of pure neurasthenia.

They were undoubtedly rich and idle people, but also endowed with a certain sense of humor.

In the center of the doggy necropolis there is a small monument whose inscription proclaims the following ripiudos although funny verses:

"Happy are those of us who are here around this pedestal that living well or badly we remain here when we die. But men our masters with uncertain future in their second existence live with death attentive... for they 'settle the account' for them at the moment of death".

Half jokingly, half seriously, the philosophy of this harangue is that there are several kinds of immortality. Animals would have to settle for a second division: the memory they left in their owners, enhanced at most by these burial sites designed to rescue from the fallible human memory the anecdotes of their lives and even their deaths.

There is, in fact, a tile reminder of a certain Nancy who "was killed by a Packard". Human immortality is made of a different stuff: it does not merely consist of being remembered, but allows you to remember yourself, albeit after "settling the account".

If you want something, it costs you something. My friend Francisco Soler has just published a book with the appropriate title a few months ago: After all, where he explains that the hope of that immortality premium, far from being a kind of balm or consolation that pious souls seek to escape the horror of dying, it is a warning to navigators, because when we close our eyes for the last time, instead of thinking something like: "everything that was given is finished", we will have to keep in mind the balance of "debit" and "credit", to settle any outstanding debt.

The Argentine poet Borges, who as a young man flirted with the idea of throwing in the towel, removed it from his mind with this elementary consideration: "The door of suicide is open, but theologians say that in the shadow of the other realm I will be waiting for me".

However, there are many kinds of hopes. Some console themselves with very little: the prospect of being converted into unpunished is undoubtedly the most minimalist of all.

It is followed by ranking the expectation that those who survive us will only remember the good times we had with them, forgetting or forgiving the misdeeds or even the fact that we were, without palliation, bad people. There are even those who are not satisfied with having swindled their fellow man and pretend to deceive posterity by burying under their own coffin any evidence of past iniquities, or by hiring a mercenary pen to draw up a false biography embellished with hagiographic touches.

Auguste Comte, in his Positivist catechism, tried to prevent posthumous frauds, establishing a tribunal formed by priests of the "Religion of Humanity" that would decide, in the absence of ultraterrestrial instances, what should be the final destiny of the deceased. Their salvation or condemnation would be recorded in a carefully guarded book. I do not think that even in this way the irremissible application of the sentences could be completely assured, especially if an absent-minded comet should happen to stumble upon our planet.

For me, being a Christian, these "passive" immortalities are neither hot nor cold. I don't care if a chorus of praise can be heard at my funeral, not to mention the fact that maybe I don't even get that.

And whether a hundred or two hundred years from now there will still be someone who has the idea of reading what I have written, what difference does it make? Jesus Christ's promise to us to be able to see Him, and the Father, and the Holy Spirit "face to face" pales the attractiveness of any other reward. post mortem.

I am not one of those who like to speculate about what we will do or how we will feel when we "are in Heaven". Some people who share my faith are more prone to this kind of speculation and worry about leaving behind loved ones or experiences they are very fond of.

Although not particularly novelistic, it seems to me that worrying about such extremes is futile. C. S. Lewis recounts in A pity under observation the last moments he shared with his wife. As far as he himself is concerned, they were particularly intense, and he was able to have an extraordinary spiritual communication with her. However, he adds with a feeling fifty-fifty divided between desolation and consolation: "but she was already looking towards eternity".

Those who are left alone are not those who die: it is us. Something teaches the Christian the blow that the Master gave to the Sadducees when they asked him whose spouse she would be in the hereafter, the one who in life was the widow of seven brothers.

Nevertheless, it is understandable the feeling that many have -we have- that there are things in earthly existence that it would be a pity to leave completely behind when the trumpet announcing the passing from this world to the next sounds. Without prejudice to my lack of fondness for eschatological speculation and my firm will to abide by the teachings of the Church, I believe that something can be said to appease whatever is justified in such uneasiness.

I will introduce it by quoting again some verses of Borges, that great unbeliever (or maybe not so much?):

Only one thing is missing. It is oblivion. God, who saves the metal, saves the dross And figures in His prophetic memory the moons that will be and those that have been.

Finite memory

For an elderly person, for whom forgetfulness has ceased to be an anecdote and become a habit, nothing could be more hopeful than the existence of a Memory capable of housing under its immense vaults nothing less than the infallible repository of all lost memories.

This is particularly well understood by those of us who have writing as a profession and often suffer the paranoia of losing our texts. I am reminded now of my teacher Leonardo Polo's visits to Seville. When he got off the train I would offer to take his wallet to him, and he would take advantage of the occasion to observe ceremoniously: "Be careful, because I am carrying unpublished works..." Polo's unpublished works!

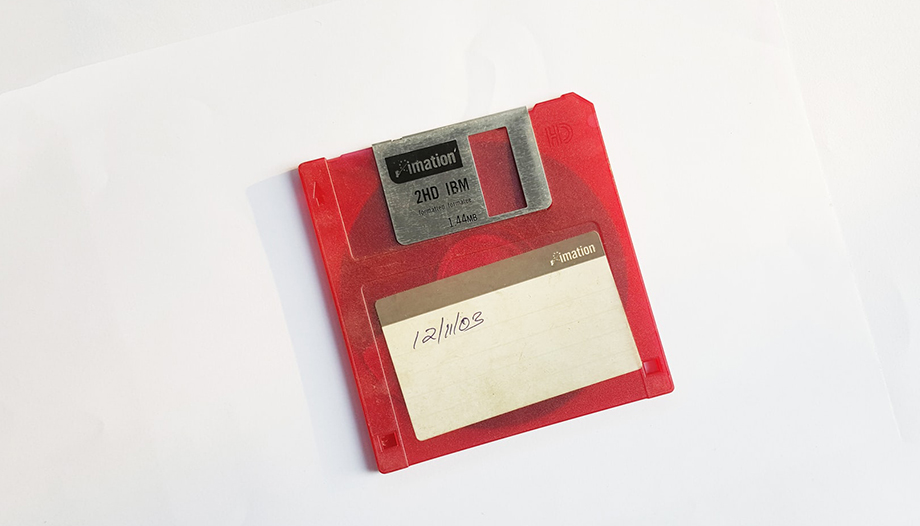

He at least had a court of disciples willing to preserve them. But what about my unpublished works and those of Paco, Pedro, Carmen, etc., etc.? There was a time when from time to time we would record our complete works on CDs so that those intimate treasures would not be lost forever. What a disappointment we were when we learned that the preservation of such repositories is only assured for a few years! Even paper turns out to be more durable.

Now we place our trust in something more spiritual, since we store the sum of our occurrences in "the cloud". Do we really believe that the aforementioned cloud will not dissipate into thin air like an evanescent mist?

Physicist Frank Tipler wrote an exciting book entitled Physics of immortality. The eternal life offered there is not given by God, but by science. There is still a long way to go before it is available: the day after tomorrow at the earliest, which means that we will not see it in life, but be calm: since he promises, he also promises for it. retroactive effects.

In other words, we will have a technological resurrection and thus we will all enter together hand in hand into a new life within this same cosmos. It will be a return to a virtual life, because there would be nowhere to put so many bodies, especially if they insist on traveling to the beach on weekends. Apart from this and other renunciations, in order for the thing to last indefinitely, it will be necessary to overcome -also with the help of the knowledge of the future- all the cracks that make this rogue world perishable. Little by little the thing gets fat and in the end we have to swallow the millstones the size of the galaxy. I prefer to stick to the faith my parents passed on to me.

But, if we are to save, there is also something recoverable in Tipler's wild speculation. It always struck me that even the most delicate expressions of an artist, the most sophisticated harmonies of a concert, the most brilliant inflections of a speaker, can be encoded, stored and reproduced in the ups and downs of a methacrylate disc or in strings of zeros and ones recorded in a pendrive. The spirit surpasses the material, but its corporeal imprint is something quite tangible. Pulling upwards, Tipler concludes that all the vicissitudes of a human life, however long and rich, could be described with 1045 bits of information. Every last sigh, feeling, desire and reasoning, second by second, and even the film of the manufacture, evolution and destruction of each and every molecule in our body would be recorded there.

In short: everything, absolutely everything, the material and the spiritual, insofar as the latter is translated into words, gestures and describable experiences.

As I am not a materialist, I must add that in this accumulation of information my conscience, my self, my soul, etc., would not be included. But it would include the history of the totality of the actions and passions of my spirit, down to the last comma or tilde. This is, of course, a fantastically large magnitude, a 10 followed by forty-five zeros. To get an idea of how big it is, I will say that it is enough to add thirty-five more zeros to count up to the last atom in the universe.

So what? It's still a finite number that admits of being fully designated with a comically succinct expression.

God, on the other hand, is infinite. In any lost corner of his Memory (if you'll pardon the impropriety of the expression) are contemplated not only the last of my hair (as I am quite bald, that does not have much merit), but also the last of the details, conversations, gestures, sneezes, hiccups, outbursts of rage, undefined discomforts and well-being, moments of glory and exaltation, or of loving tenderness, etc., etc., etc., etc., that there were, are and will be in my life, that of my wife, that of my daughter, and that of the last Martian that inhabits the last exoplanet of the exoplanet, etc., etc., that there were, are and will be in my life, my wife's, my daughter's, and that of the last Martian inhabiting the last exoplanet. And that Memory will remain perfectly preserved and indelible for ever and ever.

This means that, in principle and in a prioriis more disturbing than anything else. Because, since taking pictures with the cell phone is free, one of the greatest pleasures we have is to delete the 90% of those we get. I, at least, am not so paid for my existence that I want to keep an untouched record of everything that is in it. It is like laughing at the dossiers that detective agencies prepare to ruin the careers of politicians.

But here's the best part: I've been a father and I've mastered the technique of "turning a blind eye"; I can forget some of my offspring's less than glorious episodes without actually forgetting them. It is therefore easy for me to apply the corresponding rule of three. The best thing is not that I am infinite e very loyal, but that above that the Memory of God is love.

When we return to Him, we will be able to dive into it happily, without the need for embarrassment. Let's go for a walk with the compilations, the diaries, the exhaustive curricula! Let's make fun of our memory failures, even of the threat of being diagnosed with Alzheimer's!

Wherever we go we will find again (with a golden iridescence that the most romantic of nostalgics would like) all that in our laughable lives deserves to be remembered... and much more: neither eye has seen nor ear heard...

Professor of Philosophy at the University of Seville, full member of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, visiting professor in Mainz, Münster and Paris VI -La Sorbonne-, director of the philosophy journal Nature and Freedom and author of numerous books, articles and collaborations in collective works.