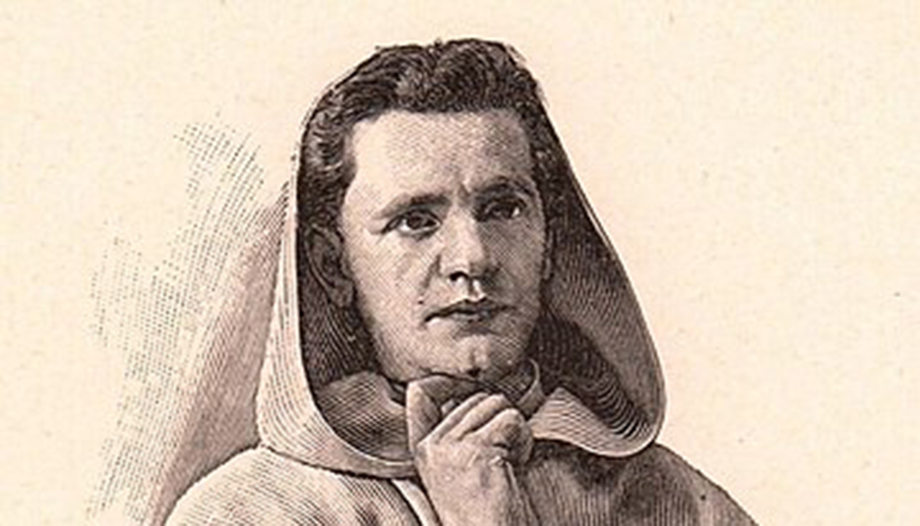

Sertillanges, an illustrious Dominican, died at the age of 84 on July 26, 1948. Neither the date, at the beginning of summer, nor the circumstances, nor even the year were the best for him to die. Few people heard about it. And hardly any obituaries or personal memories were written, apart from those of his companion in the order who acted as his secretary, Marie Dominique Moos, from whom almost everything we know about him comes from.

He was born in Clermont-Ferrand (1863), in front of Pascal's house (about whom he wrote an essay), in a very practicing family. In high school, he was a student at the same time alert and distracted. He told Moos that he liked to do poetry during math classes and to solve problems during literature classes. But he already excelled as a speaker. It would be one of his great vocations, along with intellectual life, teaching and religious life in which everything would come together.

Vocation and training

In 1883, he entered the Dominican novitiate and went to Belmonte (Cuenca), where they had settled when they were expelled from France in 1880. In 1885, he went to Corbara, in Corsica. There he studied theology, was ordained (1888) and began teaching (1890-1893). In 1893, he was assigned to Paris, as first secretary of the newly founded Thomist Review.

He then began to write articles systematically (more than 700 in his lifetime). From 1900 to 1922 he held the chair of philosophical morality at the Institut Catholique de Paris. This gave rise to numerous courses, conferences and essays, and many publications.

He left an immense work, specialized in the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, but with many ramifications. In a famous French commentary on the Summa (La Revue des Jeunes) dealt with the questions of God and morality. This would give him the basis for several essays: one, on God and modern thought; another, on the morals of St. Thomas; and a final, voluminous essay on the problem of evil. In addition, it is worth mentioning, among others, his two volumes on the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, two others on Christianity and philosophiesand of course, Intellectual lifea true classic.

Although he does not entirely escape the apologetic tone of the time, he had a serious concern for dialogue with modern thought, culture and science, and he was very well informed (and had a prodigious memory). That makes him original and profound.

The 1917 sermon and the "French peace".

Lives sometimes have moments of tremendous intensity. In 1917 France was at war with Germany and Austria (1914-1918). The French population was outraged at what it considered to be a new aggression by its uncomfortable neighbors, and wanted to put an end to it once and for all. On August 1, 1917, Pope Benedict XV (1914-1922) issued a letter to the governments to put an end to this useless massacre by reaching agreements. It was a courageous and wise proposal, but it was not well received by the people of the time. Especially in France, by the secularist government, but also by many Catholic patriots.

In these circumstances, Sertillanges was asked to speak. At 53, he was a regular speaker in Parisian forums. Sertillanges, who had previously defended the pontiff, made a nuanced speech at the Madelaine in Paris, where he came to tell the Pope that his French children were thinking only of "French peace" (title of the sermon), that is, victory. In passing, he also ventured that it was a political issue and, therefore, a matter of opinion. The government liked him and he was congratulated (privately) by several bishops.

As is well known, the final ("French") victory was very costly for everyone and left Europe in a disastrous situation. In 1918, Sertillanges' speech (and its great value) made him the first ecclesiastic to be appointed member of the Institute of France (Academy of Moral Sciences). But the Holy See showed its regret to the Dominican order, and during the pontificate of Pius XI (1922-1939) he was removed from public teaching. He spent a year in Jerusalem, another one in Holland and the rest in the new convent of Le Saulchoir in Belgium, where he gave classes for example to Congar (1930-1932). He carried with obedience and elegance his situation, which was prolonged, and wrote a lot. In 1939, Pius XII lifted his sanctions and he returned to Paris, the year the Second World War began. Afterwards, he continued to teach at the Catholic Institute and to write until the end.

The impact of Christian truth

Sertillanges' work is of interest as an authoritative expositor of the thought of St. Thomas. Also in the frontier questions of Christian truth, such as the subject of evil or the soul, in an increasingly materialistic cultural milieu. He made a remarkable critique of some medical approaches, with great sense and open-mindedness, which is still valuable. And he dealt with Bergson, and wrote some essays and conversations with him.

In addition, as he had an enormous cultural background, he was forming a general idea of the historical position of Christian thought in the whole of Western philosophy. He was perfectly aware of the contributions of revelation, and of the before and after that it represents in the history of thought. All this is what will be taken into account in the debate on "Christian philosophy", which was widely echoed in France in the 1930s and after.

Christianity and philosophies

Christianity and philosophies is a work of maturity and a valuable synthesis, in two volumes. In the first, he reviews the history of Christian thought, in the order promised by the subtitle: the evangelical ferment, the elaboration over the centuries, the Thomistic synthesis.

He begins by warning that Christianity is not a philosophy in the modern sense of an abstract synthesis, but a way of life, and, in that sense, a wisdom. He describes its characteristics and novelties, on God, creation, the structure of the human being, the characteristics of the person, and of moral and social life. Then, he deals with the "recovery of the past", which is the absorption of Jewish principles and Greek philosophy. He goes through the "new elaboration" made by the Fathers of the Church on this material. And he concludes in "The Thomistic Synthesis", which is an intelligent overview, including at the end the inevitable "gaps in the system", especially in relation to changes in the conception of the world, which require coherent developments.

The second volume is a survey of the later history of Western philosophy. Sertillanges argues (at the beginning of the first volume) that what is most valuable in modern philosophy is due to Christian fertilization, which has also recovered the best of ancient philosophy. Despite this clear position, he treats with benevolence and discernment, first, the scholastic decadence and the "Cartesian revolution", with its posterity. He studies English and French empiricism (Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Condillac), Kant and his successors (German idealism). He dwells on the spiritualist renewal of France (Ravaison, Boutroux, Gratry, Blondel, Bergson), one of the most interesting chapters. And he also devotes a chapter to "German neo-spiritualism", where he reviews, among others, Husserl, Heidegger and Scheler.

It has the interest of being a history with a sense of thoughtful, constructive and Christian judgment, and which, as he recommends in his book on the intellectual life, rather than confronting, prefers to add up what is valuable, without ceasing to present the objections that seem to him opportune. He concludes on what he believes is needed for a Thomistic revival.

The first thing is to distinguish philosophy from theology methodically; the Christian thinker must test the extent of his own thinking with his own forces, without mixing the two fields; only in this way can he engage in dialogue. The second is to reject the logicism that has been the disease of scholasticism. The third thing is to have a scientific culture and a historical sense because, although truth is timeless, it has a temporal expression and context, and also a history of how it is achieved, which is very useful to know. "There is one condition, he says at the end, for that fruitfulness, [...] and that is that the study be done in a spirit of doctrinal interiority and not in a merely documentary or anecdotal spirit. The pure historian tends to empty the system of all properly philosophical interest. The pure philosopher tends to fix and immobilize it [...]. The philosopher-historian respects life, he enters into it and fosters it. He invites the system to have new blooms and fruits". And so he hopes for a revival of the Christian synthesis.

The idea of creation

The idea of creation and its reflections in philosophy (1945) is a beautiful essay and also a work of maturity, synthesis of synthesis. It is completed with The universe and the soul (1965), a publication composed of several writings gathered by his secretary.

Sertillanges is, perhaps, less brilliant and synthetic than others (Gilson, Tresmontant) who have dealt with the novelty of the Christian idea of creation and its implications in thinking about the order of beings, and the idea of God himself, separated from the world, time and space. And of the relationships of dependence and autonomy between the Creator and his creatures. But it contains more detailed analyses.

The essay begins with an analysis of the meaning of an absolute beginning of things and time. It explains how the origin in time, which today is postulated by modern science, was not perceived in ancient science, but which, strictly speaking, remains undemonstrable, since an absolute beginning (with nothing before) cannot be assured. It deals with creation and providence. And of creation and evolution. And of the miracle in creation. And of evil.

Particularly striking is the weight with which he treats the subject of evolution, with analyses that are still valid, because he was perfectly aware of the limits within which each field of knowledge operates: theology, philosophy and the sciences. "Every birth is a biological fact and at the same time a fact of creation: there is no reason why the same should not happen with the species. The only difference is that here instead of a repetition, there is an innovation, an invention [...]. And the meeting of these two facts: a biological invention that has the character of a natural spontaneity and an activity transcendent to nature with the name of creation, this meeting, I say, responds to a providential law [...]. The unity of creation is not a vain word. It is a symbiosis, and to see this symbiosis in duration, as much as in extension and in permanence, is to accept evolution." (ch. 8).

Intellectual life

The foreword to the fourth French edition of Intellectual life tells that Sertillanges wrote this classic during a two-month summer stay in the countryside (1920). He describes the regime of intellectual life that he himself lived. It is inspired by the advice of St. Thomas Aquinas, and also by that of the Oratorian Alphonse Gratry (1805-1872), a great Christian thinker and author of some of the most important works of his time. "tips for the conduct of the spirit".with the title The sources (Sources), the first chapter of which deals with "on silence and the morning's work".. Gratry influenced quite a few themes on Sertillanges: the sources of knowledge of God, evil, the soul....

Sertillanges' essay is longer and more complete. It covers everything from the general organization of life to the organization of memory and note files, with unforgettable advice. He begins by describing the intellectual vocation and ends with what a Christian worker is and what intellectual work entails in human maturity.

Style is not only a syntactic or grammatical requirement, it is a requirement of spirit: humility and love before the truth, charity before others, purity of intention, overcoming selfishness, the effort of synthesis with the desire to add and not to divide. "To seek the approval of the public is to rob the public of a strength it was counting on [not to be told what it already knows] [...]. Seek God's approval. Meditate the truth for yourself and for others. [...] At our desk and in that solitude where God speaks to the heart, we shall listen as the child listens and write as the child speaks." (chapter VIII). "It would be desirable that our life be a flame without smoke, without waste and without impurity. It is not possible, but what falls within the limits of the possible has also its beauty and its fruits are beautiful and tasty." (chap. IX).