Translation of the article into English

When Joseph Ratzinger became Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1982), he was a well-known German theologian, with a not very large work, a successful book (Introduction to Christianity, 1968) and a small manual (Eschatology). In German he had quite a few articles and a few books. Little else. It was to be expected that his work as Prefect would put an end to his production. Moreover, he worked intensely and absorbingly for many years (1982-2005): twenty-three, as many as he had been professor of theology (1954-1977). But, fortunately, he did not disappear as a theologian. And this is due, in the first place, to the fact that the position placed him before the great questions raised in the Church; before what John Paul II wanted to do; before the doctrinal problems that came to the Congregation, the work of the ecumenical commissions, of the International Theological Commission and of the Pontifical Biblical Commission, and before the concerns and consultations of the world episcopate.

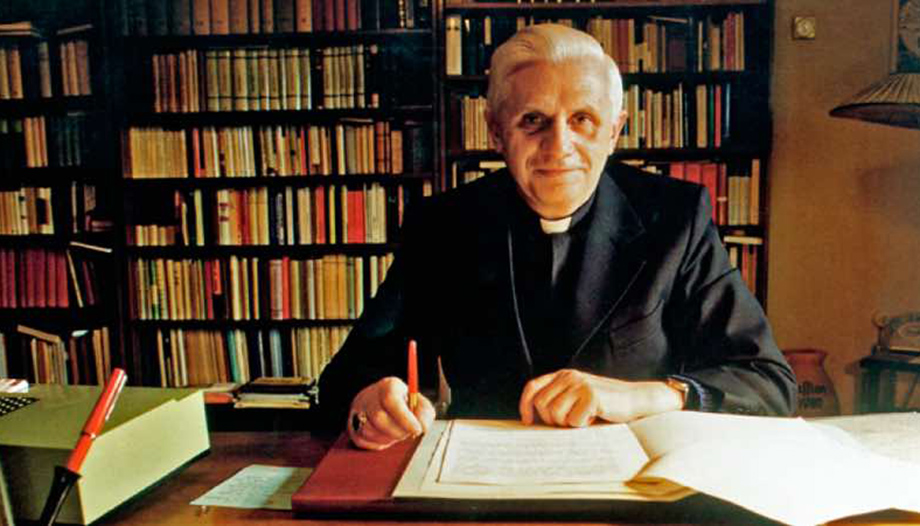

A way of working

Another prefect would perhaps have passed on the responsibility of studying these matters to expert theologians, reserving to himself an ultimate prudential judgment. He counted on other experts, but being himself an "expert theologian" he was obliged to have a clear and personal mind on these questions, and to increase his knowledge and develop his judgment. And it was up to him to explain it in the various forums of work in the congregation and in meetings of bishops. For example, in 1982, he gave a course to Celam on Jesus Christ; and in 1990, another to the bishops of Brazil on the situation of catechesis, collected in The Church, a community always on the way (1991). Most of these interventions, conferences, courses and contributions to tributes (Festschrift) were written by him, unlike what is normal in this type of position. He wrote them in pencil and in small handwriting. And he retouched them for publication. Then, with remarkable perseverance, he would put them together in books with a certain thematic unity, retouching them again and carefully explaining the origin of each text. In this way, the threads of the story, which come from his time as a teacher, are developed, enriched and coordinated over the years. Thus, his work is not a collection of occasional writings to get out of the way, but a powerful body of minds on the great themes.

A media impact

It is certain that, given his personality and shyness, he never thought of a media strategy. However, it did happen. The first was a surprise book interview, Report on the Faith (1985), on the application of the Council, in response to journalist Vittorio Messori. Uncomfortable, because it was still in bad taste in ecclesiastical circles to insinuate that something had gone wrong, despite the tremendous statistics. No one wanted to give reasons to the traditionalist reaction. But Joseph Ratzinger did not like this stupid two-sided scheme. He had no doubts about the value of the Council, but he had misgivings about the drifts. Later, the new magazine 30Giorni, of Comunione e Liberazione, which was born in 1988 and closed in 2012, disseminated his conferences and interviews in many languages, generating a growing interest, and later collected them in Being Christian in the neo-pagan era (1995). In 1996, he published an interview with Peter Seewald, The Salt of the Earth, and in 2002, God and the World, which allowed him to express himself with frankness and simplicity. In 1998, when he was already a well-known personality and his conferences were increasing, Zenit came out, which translated them and immediately distributed them on the Internet in many languages. This helped to multiply the editions of his books, because everything was of interest. And minor works and preaching from his time as a professor and when he was bishop of Munich were recovered. In a difficult time for the Church, Cardinal Ratzinger had become the mind of reference for many intellectual questions, which accompanied the work of renewal of John Paul II. And this grew until he was elected Pope in 2005.

In this way, he went from a few known works (above all, Introduction to Christianity) to a considerable collection of books in many languages, with a certain dispersion of titles. These materials were later reordered, again systematically, for his Collected Works (O.C.).

Work in the Congregation

His work in the Congregation was, in the first place, to follow Pope St. John Paul II in his endeavors. Especially in the encyclicals of greater doctrinal commitment: Donum vitae (1987), on the morality of life; Veritatis splendor (1993), on the foundations of Catholic morality; and Fides et ratio (1998), as well as the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992). On each of these documents, there is much previous work and important subsequent commentary by the then Cardinal Ratzinger. On the encyclicals and moral questions, for example, the book Faith as a path (1988). The whole movement of John Paul II and his initiatives on the millennium, the purification of the historical memory, the thematic synods, and ecumenical relations demanded a lot of work from him. He also had to deal with the most difficult aspects of the Church, the grave sins of the clergy, which were then reserved to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. It was up to him to clarify and confront the whole crisis regarding pederasty, intervene in cases, demand investigations, renew the protocols of action and promote adequate canonical expression. In addition, there were six major areas of doctrinal tension, which required a great deal of theological discernment. We divided them into two groups: those having to do with the coherence of Catholic theology, and those having to do with ecumenical dialogue and dialogue with other religions.

Discernments on Catholic theology

1. Modern culture produced and produces questions on doctrinal and moral issues, with all that is uncomfortable to believe (Divinity and Resurrection of Christ, Eucharistic presence, eschatology, angels...) or to practice (sexual morality, gender issues, no to abortion and euthanasia). They required constant clarifications, such as, among many, the apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis (1994) on the impossibility of the female priesthood; and corrections: Küng, Schillebeeckx (1984), Curran (1986)..., which were discussed with the authors, and deformed without limit in the media.

2. During the Council there had been a certain transfer of doctrinal authority from the bishops to the periti and theologians. This sometimes encouraged an unbalanced protagonism. For the faith is not sustained by theological speculation, and is better expressed in the Liturgy and prayer of the faithful than in the offices. Thus was born the Instruction Donum veritatis, on the ecclesial vocation of the theologian (1990). With his commentaries and other writings, the Cardinal would compose The Nature and Mission of Theology (1993).

It also concerned the authentic interpretation of the Council, whether it should be based on the approved "letter" or on the "spirit" of the Council, incarnated in certain theologians, a shocking proposal made by the historian Alberigo. From another point of view, there was Lefevbre's criticism of the Council, which occupied the Prefect a lot, trying to avoid a schism. In addition to the Report on the Faith, Joseph Ratzinger had already written a great deal on the contribution of the Council. All collected in volume XII of his complete works (2 volumes in Spanish).

4. On the other hand, the communist ideology, with points of contact with the Christian soul (concern for the poor) but with very distant presuppositions and methods, pushed towards total, redemptive and utopian revolution, and not towards NGOs, modest and transforming, which would only resurface after the ideological gale. Moreover, in the explosive social situation of some Latin American countries, it had given flight to the Theologies of Liberation and to revolutionary commitments successful in overthrowing governments and disastrous in managing nations. A discernment was needed, which was made in the Instructions Libertatis nuntius (1984) and Libertatis conscientia (1986). Besides correcting the work of Leonardo Boff (1985), who did not admit it, and dialoguing with Gustavo Gutierrez, who never had a process and evolved.

Discernments in ecumenism and with other religions

1. Ecumenical relations required clarification: first with the Anglicans, then with the Orthodox, especially on the meaning of the communion of the particular Churches in the universal Church and on the Primacy. With the Protestants, a historic agreement was reached, with nuances, on the classic theme of justification (1999), and the sacrament of Holy Orders was discussed. The notion of "communion" (and its exercise), very important in the theology of the 20th century, is crucial for the Orthodox to be able to understand themselves in communion with the Catholic Church, apart from the historical and mentality difficulties. Hence the Letter Communionis notioon some aspects of the Church considered as communion (1992). It relates to many of the Cardinal's earlier and later writings on ecclesiology and ecumenism (volume VIII of his O. C.).

2. The dynamism of Christian life, especially in India but also in Africa, demanded a mind on the value of religions, religious syncretism and the place of Christ and the Church, also on liturgical inculturation. The letter Orationis formae (1989) on the form of Christian prayer, and the notification on the writings of De Mello (1998) qualified possible syncretisms. On the other hand, the Declaration Dominus IesusThe Declaration on the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church (2000) laid the theological foundations for the Church's dialogue with the religions of the world at the beginning of the third millennium. The Cardinal worked extensively on this theme, both before and after the Declaration. His lectures at the Sorbonne (1999) stand out. With this and others, he published Faith, Truth and Tolerance. Christianity and the religions of the world (2003).

Three major topics

In the mind of the prefect and theologian there were, however, three other themes. The first is the Liturgy which, in his growing experience, is the soul of the life of the Church, where he expresses his faith. He collects the many interventions on liturgical themes, relaunched during his time as bishop of Munich. In addition, he is able to compose a new essay, The spirit of the liturgy. An introduction (1999) on the essence and form of the liturgy and the role of art. In parallel, he compiles his preaching on the liturgical seasons and the saints. And he reaffirms that true theology must draw its experience from holiness. They make up volume XIV of his O.C. Then there is his concern for the new exegesis, from which he has learned much, but which seems to him to mediate too much between the Bible and the Church, and which can alienate the figure of Christ.

The document of the Pontifical Biblical Commission on the Bible on The interpretation of the Bible in the Church (1993) did not enthuse him. He took advantage of the honorary doctorate at the University of Navarra to speak about the place of exegesis in theology (1998). And he had been shaping a "Spiritual Christology" with a believing exegesis for years. He had already published Let us look at the Pierced One (1984) with the Celam course on Jesus Christ (1982) and other beautiful texts on the Heart of Jesus. And in the book Un canto nuevo para el Señor (1999), in addition to materials on liturgy, he collected two courses on Christ and the Church (one at the Escorial, 1989); he also vindicated the living figure of the Lord in Caminos de Jesucristo (2003). He wants to retire to write this "Spiritual Christology", with an adequate exegetical background, but he will only be able to do so, at times, when he becomes Pope.

Finally, in conferences to specific requests, he develops a "new political thought" on the situation of the Church in the post-Christian world. He collects them in several books: in Truth, values, power. Touchstones of the pluralistic society (1993); in Europe, roots, identity and mission (2004), in which, among other things, there is the famous dialogue with Jürgen Habermas (2004); and in The Christian in the crisis of Europe (2005), with his last conference in Subiaco, on the eve of the papal election.

Famous themes appear: "the dictatorship of relativism", the need for a pre-political moral foundation ("etsi Deus daretur"), the convenience of "broadening reason" in the face of the reductive pretensions of the scientific method, and also that the new sciences function, de facto, with "another first philosophy".