Old and New Testaments complement each other. They are not two blocks of books in conflict, but a joint testimony of a single salvific plan that God has progressively unveiled.

These are not two successive and exclusive stages in which, once the goal is reached, the first steps would lose their interest. They are, instead, two moments of the same plan, where the first prepares the way for the second and definitive one.

Even after the goal is achieved, preparation is still essential for the end result to work properly. The books of the Old Testament are not like cranes and scaffolding, which are necessary to construct a building but are removed once the work is completed.

They are rather like medical studies for a doctor: a moment prior in time to the practice of his profession, but once the degree is obtained, the medical practice is based on the knowledge acquired. Continuing education is always required, going back to study. Something similar happens with the relationship between the Old and New Testament.

The Old Testament is a preparation for the New, but once the fullness of revelation is reached in the New, its accurate understanding will require a thorough knowledge of the Old. At the same time, the Old Testament will continue to offer permanent references to which it will be convenient to return again and again, especially when it is necessary to face new challenges in the interpretation of the New Testament.

St. Augustine, in his commentary on Exodus 20:19 (PL 34, 623), expressed the relationship between the two with a concise phrase: "The New Testament is latent in the Old and the Old is patent in the New."

With his usual rhetorical brilliance, he expresses the conviction that the reading of the books of the Old Testament alone, although comprehensible, does not allow us to grasp their full meaning. This is only fully achieved when it is integrated with the reading of the New Testament.

At the same time, it indicates that the New Testament is not alien to the Old Testament, since it is latent in it, within the wise plan of God in his revelation.

To explain in detail the quotations, allusions or echoes of the Old Testament that permeate the passages of the New Testament would require many pages, which would exceed the limited framework of this essay. Therefore, we will limit ourselves to pointing out some simple examples taken from the Gospel according to St. Matthew that will help us understand the importance of knowing in depth the stories and expressions of the Old Testament. These show us the way to recognize Christ in the reading of the Gospels.

The genealogy of Jesus

The Gospel according to Matthew begins by showing that Jesus is fully integrated into the history of his people: "Genealogy of Jesus Christ, son of David, son of Abraham." (Mt 1:1). From there, three groups of fourteen generations are listed, in which numerous points of contact with characters and texts from the history of Israel can be seen.

Especially significant are his relationships with the two characters mentioned in the heading: David and Abraham. The fact that they are listed fourteen generations three times is significant since, in Hebrew, fourteen is the numerical value of the consonants of the word David (DaWiD: D is 4, W is 6 and the other D is 4 more). This indicates that Jesus is the Messiah, the expected descendant of David.

The Announcement to Joseph

At the end of the genealogy, an angel of the Lord explains to Joseph the virginal conception of Jesus and gives him precise instructions: "Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary your wife, for that which is conceived in her is the work of the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins." (Mt 1:20-21).

The angel uses the same words that were used to announce to Abraham that Sarah "she shall bear a son, and thou shalt call his name Isaac." (Gen 17:19). In this way, the evangelist delineates the figure of Jesus with allusions to literary traits typical of the biblical literature on Isaac.

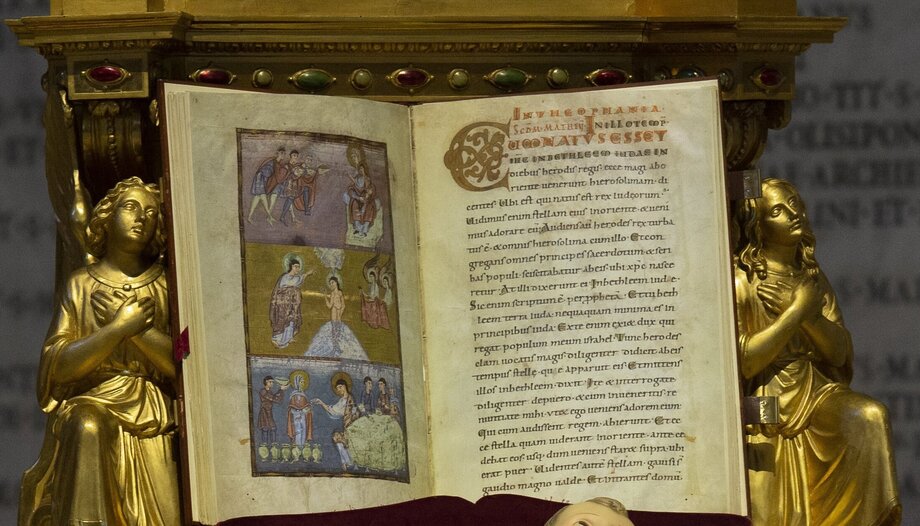

Bethlehem, the Magi, Herod, Egypt

As for David, it is important to note that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, the city of David: "After Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judah in the time of King Herod, Magi came from the East to Jerusalem, asking: -Where is the King of the Jews who has been born? For we saw his star in the East and have come to worship him. When King Herod heard this, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him. And he called together all the chief priests and the scribes of the people, and asked them where the Messiah was to be born. -In Bethlehem of Judah," they told him, "for so it is written by the prophet: And you, Bethlehem, land of Judah, are certainly not the least among the chief cities of Judah; for out of you shall come forth a leader who will shepherd my people Israel. Then Herod, calling secretly for the Magi, was carefully informed by them of the time when the star had appeared; and he sent them to Bethlehem, saying to them, "Go and inquire well about the child; and when you have found him, let me know, that I also may come and worship him." (Mt 2:1-8).

The text is very expressive, since, on the occasion of the Magi's question, a quotation from Scripture is used to show that Jesus is the awaited Messiah, the descendant that the Lord had promised to David, and for this purpose the prophecy of Micah (Micah 5:1) is mentioned.

Shortly thereafter, after the magi had worshipped the child, Joseph is said to have been warned in a dream of Herod's plans to kill him. Joseph immediately obeyedHe arose and took the child and his mother by night and fled to Egypt. There he remained until the death of Herod, so that what the Lord said through the Prophet might be fulfilled: From Egypt I called my son" (Mt 2:14-15).

Again, it is noted that what happened was already anticipated in the Old Testament, even if its readers had not noticed it before. Indeed, the phrase "out of Egypt I called my son" is in Hosea 11:1, although in the prophet's book this "son" is the people of Israel whom God brought out of Egypt to take them to the promised land.

This play of quotations and allusions, which can only be perceived by those who know the Old Testament in detail, is full of meaning.

It is significant that Matthew presents Jesus persecuted at his birth by a king, Herod, who wants to put him to death, and that, once saved from that persecution after Herod's death, he goes to the land of Israel from Egypt.

In this way, Jesus is being presented as a new Moses. In Herod's order to put to death all children under two years of age (Mt 2:16), the persecution that Pharaoh dictated against all Israelite children (Ex 1:16) is being made real again, and just as Moses prodigiously escaped certain death, Jesus also managed to escape Herod's sword.

Afterwards, he would go to the Promised Land from Egypt.

The Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan

The idea of Jesus as the new Moses resonates in several aspects at the beginning of his public life. Jesus goes to the Jordan, near Jericho, where John the Baptist is, to be baptized by him. He begins his public life after coming out of the waters of the river (Mt 3:13-17).

According to the book of Deuteronomy, Moses led the people of Israel from Egypt to the Jordan near Jericho (Deut 34:3) and, before crossing the river, he died after contemplating the promised land from Mount Nebo.

Jesus, as the new Joshua, successor of Moses, begins his preaching from the banks of the Jordan in the same place where Moses had arrived, in front of Jericho. It is Jesus who truly brings to fulfillment what Moses had begun.

In narrating the baptism of Jesus, it is said that "And after he was baptized, Jesus came up out of the water; and then the heavens were opened to him, and he saw the Spirit of God descending in the form of a dove and coming upon him. And a voice from the heavens said, "Jesus came out of the water. This is my Son, the Beloved, in whom I am well pleased." (Mt 3:16-17). This phrase "my son, the beloved", which is also heard in the transfiguration of Jesus (Mt 17:5), is an echo of the one in which God addresses Abraham to ask him to sacrifice his son Isaac to him: take "your son, the beloved" (Gen 22:2).

The parallel between Jesus and Isaac, which had already been delineated in the angel's announcement to Joseph (Mt 1:20-21; Gen 17:19), once again takes on a very expressive prominence. This way of presenting Jesus points out the parallel between the dramatic scene in Genesis in which Abraham is ready to sacrifice Isaac, who accompanies him without resistance, and the drama that was consummated on Calvary where God the Father offered his Son in sacrifice, voluntarily assumed for the redemption of the human race.

The Preaching of Jesus

Matthew also speaks of Jesus' preaching, presenting him as the new Moses, who goes on detailing the precepts of the Law in a long discourse from a mountain (Mt 5:1), alluding to Sinai.

There he mentions some of the Commandments transmitted by Moses, and makes some clarifications about their fulfillment, assuming an authority that did not leave those who listened to him indifferent.

Jesus does not raise a conflict with respect to the acceptance of Moi's Law.On the contrary, he ratifies their value: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to give them their fullness. Truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is fulfilled." (Mt 5:17-18). But he explains in detail the meaning and the ways to put into practice the main commandments of the Torah.

The "fullness" of which we speak is not that of a simple fulfillment of what is commanded, but a deepening of the teaching of the Law that goes far beyond the rigorous observance of what it expresses in its purest literalism.

The outline of Jesus' words (Mt 5:43-45) corresponds to an explanation of the commandments according to the ordinary procedures among the teachers of Israel at that time. First the text of the Law to be commented on is mentioned, and then the way to fulfill it according to the spirit of these divine commands is indicated. Jesus' listeners would thus hear a discourse structured in a way that is familiar to them.

In this case, the explanations are introduced in a peculiar, almost provocative way by the master of Nazareth. It is not just an ordinary contrast of opinions. He begins by saying: "You have heard that it was said...." and quotes words from the Law to which they all acknowledge a divine origin and authority, to add: "but I say unto you..."Who is this teacher who dares to correct with his interpretation what the Law of Moses says?

This way of presenting the explanation of the commandments is typical of Jesus' style. He claims for himself an authority by which he places himself beside Moses, and even rises above him.

On the one hand, Jesus accepts the Law of Israel, recognizes its authority and teaches that it has a perennial value. But at the same time, this perenniality goes hand in hand with the attainment of a fullness that he himself has come to give it, not by abrogating it in order to replace it with another, but by bringing to its culmination the teaching about God and man that it contains. He has not added new precepts to it, nor has he devalued its moral demands, but he has extracted from it all its hidden potentialities and has brought to light new demands of divine and human truth that were latent in it.

To ignore the Scriptures is to ignore Christ.

An attentive review of the pages of the Gospel, paying attention to the details that a good knowledge of the Old Testament contributes to its understanding, is a fascinating exercise, but one that would require time and space beyond the limits of a simple essay such as this one. However, the examples mentioned above can serve to discover what a reading of the New Testament in the light of the Hebrew Bible can contribute to the knowledge of Jesus Christ.

The conviction expressed in the apostolic preaching that the Old Testament is only fully understood in the light of the mystery of Christ, and, in turn, that the light of that Old Testament makes the words of the New Testament shine with all their splendor, remained unchanged in patristic theology.

St. Jerome's annotation in the prologue to his Commentary on Isaiah is well known: "if, as the apostle Paul says, Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God, and he who does not know the Scriptures does not know the power of God or his wisdom, it follows that to ignore the Scriptures is to ignore Christ."

A good knowledge of the Old Testament is necessary to know Christ in depth, since it is indispensable to grasp all the details that the New Testament points out about the person and mission of the Son of God made man.

Professor of Sacred Scripture, University of Navarra, Spain