Article 1: In search of the theological foundation for sacred and liturgical music

Article 2: In search of the theological foundation of sacred and liturgical music. A history of sacred music

"Sounds perish because they cannot be written", St. Isidore - 1

Does anyone have a recorder?

"After singing the hymn (ὑμνήσαντες), they departed for the Mount of Olives." (Mt 26:30; Mk 14:26).

James McKinnon suggests that this song may have been the second part of the Hallel Oxirr (Psalms 113-118), one of the ritual songs of the Last Supper. Even if it was not - following St. John's chronology - this quotation manifests a link between the singing at Jewish and Christian ceremonial meals. What is clear is that Jesus Christ himself sang with his disciples. However, we cannot know in what way they sang, because at that time music was not written... nor recorded.

This is the starting point for Christian music, which could not be written down until the end of the ninth century. With this, we begin the particular historical journey that we set out in the previous article. We will begin by addressing these nine centuries without writing: the challenge of a music that no one has heard again for centuries and which, moreover, was neither written nor recorded. In the 7th century, St. Isidore of Seville still pointed out the issue (Etymologies III,15): "If sounds are not retained in memory by man, they perish, because they cannot be written down".

The Church in search of its music

The music of the Christians of the first millennium encompassed much more than Gregorian chant. Nor should it be thought that Gregorian chant came into being suddenly. Of particular interest is what is being discovered about the path that led to its creation in the ninth century. Research is still ongoing.

We therefore divide these first nine centuries into three periods:

a) During the first three or four centuriesThe Christian liturgy was celebrated in Greek and with a good deal of "improvisation", since the liturgical texts had not yet been fixed. On the other hand, what we understand by early Christian chant went beyond the liturgy. In any case, the documentation preserved from the first two centuries is very scarce. We have more news of the third century and, above all, of the fourth.

b) From the 4th to the 8th century, certainly from events of the magnitude of the Edict of Milan (313) or the Council of Nicaea (325), different types of chants were created in various Christian communities.

c) In the 9th centuryCharlemagne promoted liturgical unification in his empire. The consequent unification of chant was no easy task and the process resulted in a new type of chant, Gregorian chant (note that St. Gregory the Great had been dead for two centuries!). ) Some time later, in the last two decades of the same century, the first documents with established systems of musical notation appeared.

The result? A chant - Gregorian chant - that today is known as "proper to the Roman liturgy" (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 116) and some other types of chant, spread throughout the geography. Some of them ceased to be used, such as the Hispanic Mozarabic chant; others have survived to the present day, such as the Milanese chant. John Caldwell argues that the musical art born in the Church was the precursor of modern Western music.

From Semitic chant to Latin liturgy (3rd-4th century)

Excursus: Temple, synagogue and cult

The Bible shows that in the Temple of Jerusalem, especially the first, that of Solomon (destroyed in the 6th century B.C.), the music was very elaborate, with large choirs and a remarkable variety of instruments (cf. 2Chr 5:12-14; 2Chr 7:6; 2Chr 9:11; 2Chr 23:13; 2Chr 29:25-28).

The exile came and, during the 70 years in Babylon, the People of Israel rethought many questions about their relationship with God and their worship. We will return to this point later, given its great importance. For now, suffice it to note that, after the rebuilding of the Temple (516 B.C.), the music in it experienced a significant moderation.

In the synagogue, on the other hand, the singing was austere and, in general, unaccompanied by instruments.

It is important to remember that the Temple was the place of sacrifice, while the synagogue was for the reading of the Word and instruction.

Another relevant fact: at first, Christians continued to attend both the Temple and the synagogue. However, they soon stopped going to the Temple, because the novelty of Christ and his sacrifice were something totally different from the worship celebrated there.

The Semitic influence in the Christian chant of the first centuries

According to recent studies, the earliest Christian chant had a greater presence in ceremonial meals than in the liturgy itself. Whether earlier or later, whether for their liturgy or outside of it, Christians took their cue from two forms of the chants they had known in their original environment: the chanting of the psalms and the cantillation of the readings. The psalms were sung with tones derived from tradition, but simplified: in one voice and, in general, without instruments. The cantillation was a "sung recitation", a declamatory style halfway between speech and song, which gave the text greater expressiveness and solemnity.

These two procedures will be the basis of all Christian chant. Understanding them well is the key to unravel the secrets of later chant. In any case, it seems that the melodies are not a copy of Hebrew chant. Alberto Turco maintains that they are western melodies.

... And the hymns in Greek

With the spread of Christianity, liturgy and chant soon reached other lands as well. Since we want to focus on the West, we turn our attention to events in Greece and Rome. The known world was populated by mystical religions, oriental cults and syncretism. The lingua franca was Koine Greek, even in Rome and among the Jews of the Diaspora. By then, the Greek version of the Old Testament was already in circulation. And the chanting of the Christians, on arriving in each place, was adapted as much as possible to the local context, in its Greek expression.

There was a significant proliferation of new, specifically Christian songs. Pliny the Younger wrote in an official document addressed to the emperor Trajan (c. 110): "They sing Christological hymns, as if it were a god". Joseph Ratzinger suggests that these hymns played an important role in the clarification of doctrine in early times. He goes so far as to state the following:

"The first developments of Christology, with the ever deeper recognition of the divinity of Christ, have quite likely been realized precisely in the songs of the Church, in the interweaving of theology, poetry and music." ("Sing to God with mastery. Guiding biblical indications for sacred music," Collected Works, v. 11, p. 450).

One lime and one sand

One of lime: in spite of everything, there is consensus about a certain Semitic influence on Christian chant, without being able to determine to what degree.

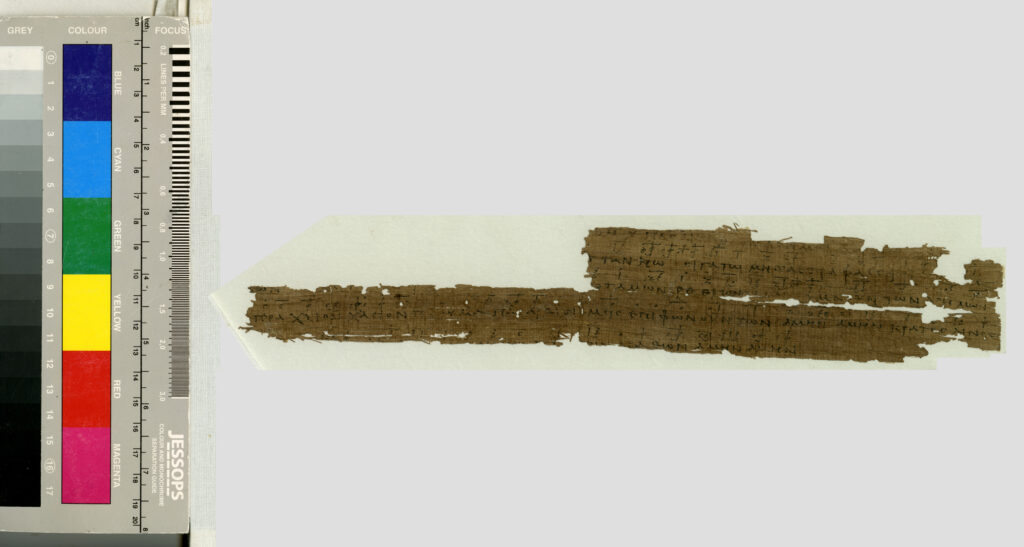

And another of sand: in the eight or nine centuries that we are traveling through, there is only one known exception of a manuscript with musical notation. It is the Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 1786, discovered in 1918 during excavations in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, and published for the first time in 1922. It is a hymn that invites all creation to praise the Holy Trinity. It dates back to the end of the 3rd century. The text is written in Greek and the music follows an alphabetical notation of Greek tradition. It is a one-voice hymn, without instruments. The photograph is available on the webas well as some modern recordingsThe song could have been a rehearsal of what that song could have been.

The point is that we cannot know how much this fragment is representative of the songs of the period. Nor is it easy to estimate the degree of local, non-Semitic influences on the chant. Added to this is the fact that many documents use the terms "psalm" and "hymn" interchangeably.

In spite of what we have shown, the new chants brought not only advantages, but also influences contrary to Christianity in some places. It is significant the progressive infiltration of gnosis, precisely through the chant, from the second century. The Church took some measures at the time.

Reservations of the Church and the Fathers

Against this background, it is also significant what we can read in the writings of the Fathers. On this point we will dwell later in the articles of the theological part, but now it is necessary to make a reference. The fact is that there are many writings against chant and, above all, against instruments. We note here that, in spite of the seriousness of the problems, no fundamental reasons are ever put forward concerning music. Let us briefly cite four of these reasons for reservations about music.

a) Possible assimilation to the mystic cults.

b) The entry of sensual elements.

c) The aforementioned influence of Gnostic doctrines.

d) Johannes Quasten points out the Neoplatonic formation of some writers and Fathers.

If these are, indeed, the most important reasons for caution, what they themselves call for is a fundamental criterion that verifies all true liturgical music. This is precisely what we will try to clarify in the course of these articles. Otherwise, why does Joseph Ratzinger explain on different occasions that the liturgy requires the song?

In the next installment, we will continue with the development of this historical period of absence of musical notation. Let's remember that the documents of the 4th century are more abundant and, since then, the facts are shown with less timidity, which allows a better reconstruction of what happened.

Below, we provide some titles of diverse subject matter and technical quality, on which to continue reading.

Bibliographic note:

For a general overview of Gregorian chant, we recommend consulting two key manuals, in Spanish and of different technical depth, by two great authors. Firstly, Gregorian chant: history, liturgy, forms... by Juan Carlos Asensio Palacios (Madrid, Alianza Música, 2003), which provides an abundant introduction to the subject. On the other hand, Daniel Saulnier, another great expert, offers in Gregorian chant (translated by Ernesto Dolado, Solesmes, 2001), an equally profound perspective, although much shorter and in a much more informative style.

For a different, but equally fundamental approach, two other manuals by Alberto Turco can be consulted. The first one, Introduction to Gregorian Chant (Città del Vaticano, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2016), presents a clear and accessible introduction to Gregorian chant, while the second, Gregorian chant: corso fondamentale (Rome, Torre d'Orfeo, 3. ed., 1996), offers a more technical and structured view.

As for the more strictly historical publications, we can follow the update proposed by Peter Jeffery in Musical Legacies from the Ancient World, in the first volume of The Cambridge History of Medieval Music, edited by Mark Everist and Thomas Kelly (Cambridge, University Press, 2018), or the volume edited by James W. McKinnon, Antiquity and the Middle Ages: From Ancient Greece to the 15th Century(Houndmills and London, The Macmillan Press, 1990).

Although somewhat older, the works of Solange Corbin are still of great value, The church to the conquest of its music (Paris, Gallimard, 1960) and Music & Worship in Pagan & Christian Antiquity by Johannes Quasten (translated by Boniface Ramsey, Washington, D.C., National Association of Pastoral Musicians, 1983). Quasten's book remains a relevant reference on the relationship between music and worship in antiquity.

An important work on the constitution of the medieval chant is With Voice and Pen: Coming to Know Medieval Song and How It Was Made by Leo Treitler (Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 2007). This anthology brings together the major articles by Treitler, an author who has left an important mark on research on medieval Christian chant.

Finally, two volumes focus on the Carolingian period, important for understanding the development of Gregorian chant and musical notation. The first is Gregorian Chant and the Carolingians by Kenneth Levy (Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1998). The second, more recent, is Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe: The Invention of Musical Notation by Susan Rankin (Cambridge, UK, New York, USA, Cambridge University Press, 2018), an essential work for understanding the creation and impact of musical notation in Carolingian Europe.

Associate Professor, Pontifical University of the Holy Cross. MBM International Project (Music, Beauty and Mystery)