The fourth preface helps us to contemplate the Easter as a new creation. Indeed, the paschal mystery has inaugurated a new time, a new world; in his second letter to the CorinthiansSt. Paul refers precisely to the death and resurrection of Christ as the principle of absolute newness first of all for human beings: "He died for all, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves but for him who died for them and was raised again. So we no longer look at anyone in the human way; even if we have known Christ in the human way, we no longer know him in that way. So if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creature" (2 Cor 5:15-17).

The same language is present in Baptism, which is precisely the immersion of each person in the paschal mystery: when parents bring their child to the baptismal font, the celebrant addresses them, announcing that God is about to give that child a new life, that he or she will be reborn of water and the Holy Spirit, and that this life that he or she will receive will be the very life of God.

Indeed, following the teaching of San PabloThanks to baptism, we have been immersed in the death of Christ in order to walk in a new life: "the old man that was in us has been crucified with him" (Rom 6:6).

But, at the same time, this newness applies to the entire created universe; it is again St. Paul who, concluding the reasoning set out above, affirms: "old things have passed away; behold, new things have come into being" (2 Cor 5:17). All things are renewed: the resurrection of Christ has opened a new stage in history, which will only conclude with the end of time, when the plan to bring all things back to Christ, the one Head, will be completed.

Indeed, the Apocalypse contemplates God seated on the throne and a mighty voice declares: "There will be no more death, nor mourning, nor crying, nor pain, for the former things have passed away. And he who sat on the throne said, 'Behold, I make all things new'" (Rev 21:4-5). The new heavens and the new earth, which will characterize our final condition, begin with the resurrection of Christ, the firstborn of a new creation (cf. Col 1:15,18).

Sunday, harbinger of endless life

This is why the Church, when speaking of Sunday, the Easter of the week, also defines it as the eighth day, "placed, that is to say, with respect to the septenary succession of days, in a unique and transcendent position, which evokes not only the beginning of time, but also its end at the end of time. future century". St. Basil explains that Sunday signifies the truly unique day that will follow the present time, the day without end that will know neither evening nor morning, the imperishable century that cannot grow old; Sunday is the unceasing harbinger of life without end, which rekindles the hope of Christians and encourages them on their journey" (John Paul II, Apostolic Letter, "Sunday is the day that will never end, that will know neither evening nor morning, the imperishable century that cannot grow old; Sunday is the unceasing harbinger of life without end, which rekindles the hope of Christians and encourages them on their journey" (John Paul II, Apostolic Letter Dies Domini, n. 26).

Easter opens, therefore, the contemplation of our life assumed by Christ and totally renewed thanks to his Passion, Death and Resurrection: He took upon himself our miseries, our limitations, our sins and generated us to a new life, the new life in Christ, which opens us to hope, because all that in us is misery and death, in Him is rebuilt and is the promise of life.

The fifth preface

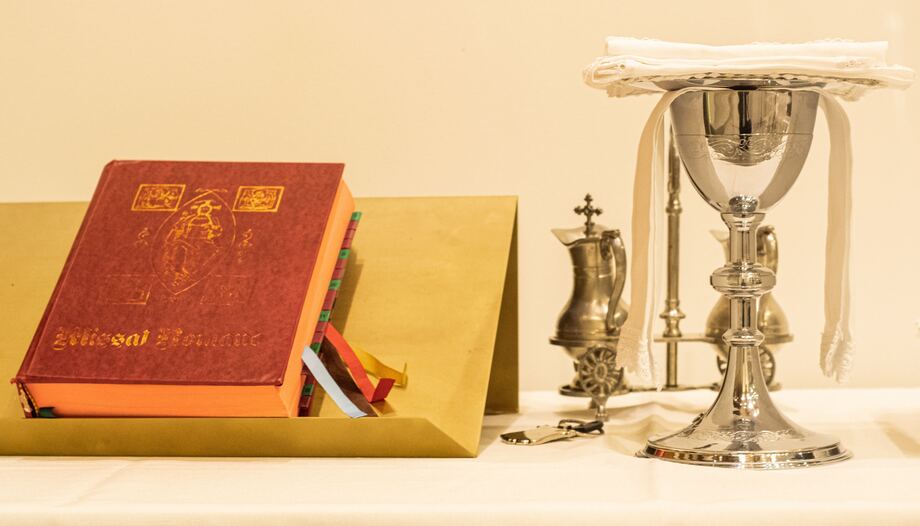

In the fifth preface, the image of the sacrificed Lamb returns, but in this case combined with that of the priest and the altar. It is a bold image, which unites in the person of Christ the three great categories of the sacrifices of the Old Covenant, thus shedding new light on the meaning of those sacrifices and opening up an unprecedented novelty.

Indeed, the entire sacrificial practice of the Old Testament was centered on the concept of holiness. (kadosh): the presence of God is something supremely strong and impressive, which arouses admiration and awe in man. It is something totally different, to the point that God is called "the thrice-holy": he is the one who is totally different both from the other gods and from the sphere of the human.

This means that, for a supplication or a sacrifice to reach the unreachable, it is necessary that this sacrifice be separated from the ordinary. For this reason, the Old Testament cult was characterized by a series of ritual separations: the high priest was a person separated from the others, either by birth (he could only be chosen from the tribe of Levi and, in this tribe, only within the family descended from Aaron), or by virtue of special rites of consecration (ritual bathing, anointing, clothing, etc., all accompanied by numerous animal sacrifices).

Similarly, the sacrificial victim was separated from all other animals: it could only be chosen on the basis of certain characteristics and had to be offered according to a very specific ritual. Finally, only a fire descended from heaven could carry to heaven the victim offered by the high priest (that is why the fire of the Temple was constantly watched and fed) and the offering could only take place in the holiest place, the closest to God, the Temple of Jerusalem.

Jesus, a new cult

Jesus, instead, inaugurates a new cult, characterized by solidarity with the brethren: Christ, in fact, "in order to become high priest," "had to become in every way like the brethren" (Heb 2:17); from the context it is clear that "in every way" does not refer only to human nature, that is, to the mystery of the Incarnation, but also and above all to suffering and death.

He is then the true victim, the only one truly pleasing to the Father, because he does not offer himself in place of someone, but is characterized by the offering of himself: the obedience of Jesus cures the disobedience of Adam.

Finally, he is the holy place par excellence, the altar that makes the offering unique and definitive. Indeed, the purification of the Temple carried out by Jesus before his Passion and Death was done in view of the erection of the unique and definitive Temple, which is his Body (cf. Jn 2:21): his Resurrection inaugurates the time when true worshippers will worship in Spirit and truth (Jn 4:23), that is, by belonging to the Church, the Body of Christ. The destruction of the Temple, which took place in 70 A.D. and was prophesied by Jesus, only sanctions this novelty in a conclusive manner.

To this is added the fact that we offer our own life always "Through Christ, with Christ and in Christ", that is, through his mediation, our offering resting on the offering that he made of himself once and for all.

Pontifical University of the Holy Cross (Rome)