A little over a year ago, the cathedral of Geneva hosted the first Eucharistic celebration after five centuries of no Catholic ceremony. A celebration that brought the ideas of reformed theology back to the table. In this article we refer to those communities that were part of a "second Protestant reformation", sponsored in Switzerland by Zwingli and Calvin. From there it spread throughout the world, until it reached the 75 million Christians belonging to the worldwide Reformed Alliance.

Their influence in the world of ideas and in society is even greater. They are also sometimes called Puritans, Presbyterians and Congregationalists. The development of these communities not only in Switzerland, but also in France, Holland, Scotland, the United States, Latin America and Korea. Calvinism has thus become a worldwide phenomenon.

Swiss origins

In German Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) preached a radicalism that displeased Luther himself. The latter clashed with the Swiss reformer at the Marburg Disputation in 1529, who defended only the symbolic dimension of the Eucharist. Zwingli belonged to the same generation as Luther, and therefore never wanted to be called a Lutheran, although he accepted the doctrine of justification by faith alone. Moreover, Zwingli saw in Christ the teacher and model, while for Luther, Christ was the Savior who forgives and gives eternal life out of pure mercy. Luther's mentality was always marked by the theology of the cross; Zwingli's by humanistic philosophy with its methods, logic and intellectualistic demands. The spiritualistic and intellectualistic tendencies of humanism were exaggerated.: no images or sacraments, but above all liturgy of the Word.

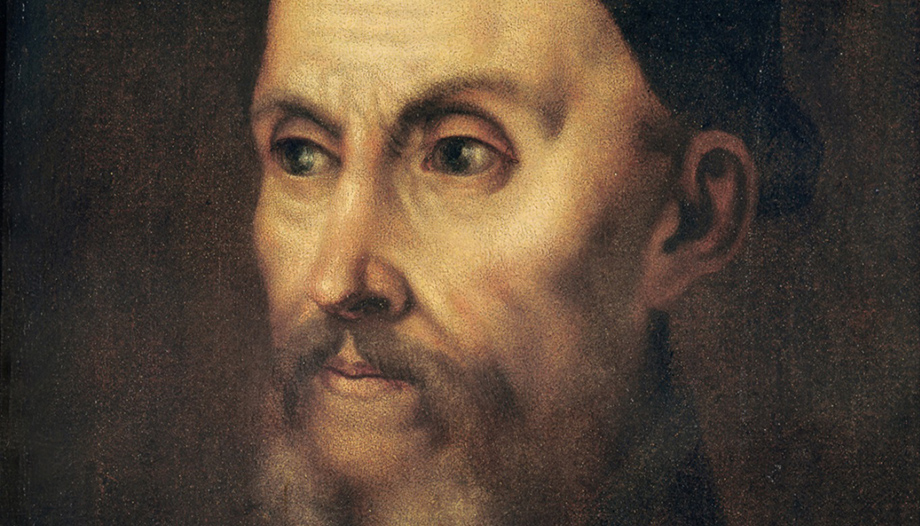

John Calvin (1509-1564) broke new ground in Protestantism. He had received a juridical formation that would influence the exposition of doctrine and the civil and ecclesiastical organization. A tireless worker, he sought to establish in Geneva the living conditions of the primitive Church. Thus, all aspects of social life were regulated: not only preaching and religious songs, but also punishing with the death penalty for blasphemy, adultery or offense to one's parents. This iron organization to which he subjected the city had some positive consequences, such as the improvement of heating, the textile industry or health care. On the very day of his death, he gathered his friends around his bedside to preach a sermon to them. When he died on May 27, 1564, the whole of Geneva wept before his coffin. He thus achieved a true theocracy under the direct rule of the word of God.

Calvin has the same conception of justification as Luther, and even intensifies it, with the "doctrine of predestination".

Pablo Blanco

Calvin expounded his doctrine in the treatise called la Christian Institutionone of the most influential works of world literature, together with the Small catechism of Luther. Calvin has the same conception of justification as Luther, and even intensifies it, with the "doctrine of predestination". He writes: "What is most noble and praiseworthy in our souls is not only wounded and damaged, but totally corrupted". Calvin identifies original sin and concupiscence, understood as the opposition between man and God, between the finite and the infinite, as Karl Barth would later say. Man is born sinful and, after Baptism, he continues to be so: "Man in himself is nothing but concupiscence". Therefore, a) man is not free, but is totally subject to evil; b) all the spiritual works of man are sin; c) the works of the just are also sin, although Christ knows them and hides them; d) justification is the mere non-imputation of sin.

2. Calvinist theology

"Calvin was a multifaceted and brilliant personality," wrote Lortz. The doctrine taught by him, even if it bears the influence of Luther, is an original product". He also had a systematic head, typical of one who has been trained in juridical science, but he also had a tender and delicate heart. Moreover," writes Gómez Heras, "Calvin knew how to imprint on his Protestantism a more universalist character than Luther," from which came the missionary dynamism of the Calvinists, their love of risk and adventure, and even their ecumenical disposition. Theologians such as Zwingli, Bucer, Bullinger, Laski and Knox have contributed a proprium to the Reformed faith, which takes on a different physiognomy in each ecclesial community. In spite of everything, there are some common elements, among which we can highlight the following, as a synthesis of the above:

a) In the reformed area, the principle of sola Scripturaand tends to the literal interpretation of the Bible. Alongside it, professions of faith are time-bound testimonies in which the community acknowledges its beliefs. The Reformed tradition has produced numerous confessions of faith, such as the Theological Declaration of Barmen (1934), the Fundamentals in perspective of the Credo of the Dutch Reformed Church (1949) and the profession of faith of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States (1967).

Although these do not enjoy the authority of the confessional writings of Lutheranism (particularly the Augsburg Confession and Luther's catechisms). There is thus no confessional writing that is binding on all Reformed communities. The congregationalist principle of the autonomy of each community even provides for the right to establish the foundations of one's own faith.

Calvinism is more concerned than Lutheranism with the concept of personal sanctification, which leads to the fulfillment of the law and the task of sanctifying the world.

Pablo Blanco

b) The concept of the person's election in Christ is nuclear: human salvation does not depend on good will or one's own dispositions, but only on faith: he who believes is predestined. In Calvin, however - unlike Luther - one finds a certain subordination of the divinity of Christ, with a certain Nestorian tendency. The classical Reformed teaching of "double predestination" (to salvation or damnation) has little relevance today. But equally the themes of faith and holiness, penance and conversion are still fundamental in Reformed theology. Calvinism is more concerned than Lutheranism with the concept of personal sanctification, which leads to the fulfillment of the law and the task of sanctifying the world.

c) The reality of the living God revealed in Scripture is also fundamental. The sovereign and gratuitous revelation of God in Jesus Christ was incisively explained by the most important Reformed theologian of modern times, Karl Barth. He shows well what is meant by the soli Deo gloria, For the Swiss Reformer was interested only in the glory of God, and not so much in his own salvation, as was Luther. This can be recognized in the teaching on the sovereignty of God: God accomplishes his will in the world in only one way, by the sovereignty founded in Jesus Christ and exercised through him.

d) – Supernatural "covenant theology". Reformed Christianity develops the thought of God's sovereignty in the perspective of salvation history and considers the Old and New Testament as a unity: the "covenant of works" and "of grace" are ordered to each other. The value of the Old Testament in Reformed Christianity finds its foundation here. The Christian's commitment to the covenant established with God is at the basis of Christian ethics ("covenant ethics") as a consequence of God's sovereignty in the world. From this positive perspective Reformed Christianity finds strength to act in the world.

e) The sacraments -Baptism and the Supper are united to the Word; they are signs and seals of the preaching of grace. Baptism is not necessary for salvation, but it is a serious commandment of Christ, which is why it is sometimes delayed for adulthood according to the Anabaptist proposal. The doctrine on the Supper - celebrated four times a year - lies between that of Luther and Zwingli. The forms of the classical doctrine (Calvin's spiritual presence and Luther's con-substantiation) are understood as attempts to understand the same Eucharistic faith, so it is no longer seen as a source of division. That is why they practice intercommunion or so-called "Eucharistic hospitality" among themselves. If in the Lutheran conception, the Eucharist is the body of Christ; in Calvin isand in Zwingli only the means.

f) In contrast to a certain anthropological pessimism typical of Lutheranism, we find a Calvinist optimism that understands the world as a task. In Calvinism, one can find a ethics of action and successwhich will bring him great success in his missionary activity. Not surprisingly, the sociologist Max Weber formulated the theory of Calvinist ethics as the foundation of the capitalist spirit, although this theory has been deeply discussed.

If for Luther religion is something fundamentally interior, in Calvin it has a markedly social dimension. In contrast to a certain Lutheran quietism, we find a Calvinist activism that favors the democratic structure: "the Calvinist," Algermissen affirms, "who acts successfully for the glory of God feels himself as chosen, as predestined. This principle would explain the economic development in Anglo-Saxon countries, where Calvinism quickly triumphed. Here, too, there are differences with the Catholic vision, which seeks to combine personal success with the principle of solidarity.

If for Luther religion is something fundamentally interior, in Calvin it has a markedly social dimension.

Pablo Blanco

The Calvinist ideal is characterized, on the one hand, by simplicity and sobriety of manners and conduct and, on the other hand, by a lively interest in social and political questions, science and art. It is the so-called "Puritan morality", which has marked - for better and for worse - the development of some countries. Ethics is seen as obedience and realization of an ecclesial order together with the social and political order. As we have seen, Calvin advocated collaboration between Church and State: they are two distinct powers but subordinate to the sovereignty of God, which must collaborate for the good of the same and unique human society. The Lutheran dualism that distinguishes between secular and spiritual power is alien to Reformed thought. Temporal power is almost identified with religious power.

3. Church and ecumenism

According to Calvin, the Church is the invisible community of the predestined, but it becomes visible in its mission to lead all. The reign of Christ is to be manifested and enforced through ecclesial ministries, and the ecclesiastical structure is therefore of decisive importance. Faith and discipline take on a priority character in the community, and the State must help the Church. This usually constitutes National churches. While in Lutheranism the temporal power prevailed over the spiritual, in Calvinism it will be the opposite, to the point that dissenters in matters of religion are offered the privigelium emigrandi.

For Calvin, faith and discipline take on a priority character in the community, and the State must help the Church.

Pablo Blanco

As far as ecclesiology is concerned, Calvin was more interested than Luther in the visible Church, its doctrine, legislation and order. In his later expositions he emphasizes the importance of the invisible Church, but he does so in order to distinguish himself from Rome: for him too, the idea that there is an invisible Church that gathers together the elect of all times is valid. But only the members of the visible Church can belong to the invisible Church, even though not all its visible members belong to the invisible Church. Christ builds his Church with Word and sacrament, and the formation of the faithful for holiness plays a fundamental role, so that ecclesial ordering is very important in his ecclesiology.

Ecclesiology is the subject of almost half of its Institutio of 1559, and in relation to the ministry, he sustains what he understands to be a New Testament testimony; that is, a ministry of four levels: pastors, doctors, elders and deacons. The episcopal ministry is not, however, necessary for the Church, hence the later "Presbyterian" developments as opposed to "Episcopalian" or Anglican.

This teaching of Calvin has been carried out in various ways in the Reformed ecclesial orders and the number of ministers has been modified, remaining at three: the pastor or servant of the Word, the presbyter (elder or servant of the Table) and the deacon or servant of the poor. These three ministries guide the community in the presbytery or ecclesial council; but the only head of the Church continues to be Christ.

However, the Christological-pneumatological ecclesiology of the Reformed claims to abandon the hierarchical structure, since the various ministries are understood as elements that are reciprocally integrated on the basis of the lordship of Christ. No ministry is subordinate to the others, and no community prevails over the others. This allows for an "open ecclesiology" and a more congregationalist or presbyter-synodal structure of a markedly participatory type. This is not, however, a system of democratic representation of the faithful, but an expression of the spiritual communion of the community founded by Christ in the Spirit.

No ministry is subordinate to the others, and no community prevails over the others. This allows for an "open ecclesiology" and a more congregationalist type of structuring.

Pablo Blanco

Synods, which were originally meetings of ministers to discuss common issues, give great weight to the "laity" (non-theologians) and local presbyteries of the local churches. elders. These are not mere advisors but have the same rights and duties in the central or community government. With this organization the reformed communities have maintained their original identity and independence, especially where - as in the Netherlands - there was no regional church government. They have thus come into being as movements of opposition to state regulation or confessional majority, as in Scotland, France, England and the Lower Rhineland. In relation to a binding magisterium, the same applies as in the Lutheran communities: the synods have a particular role, and the open character of Reformed ecclesiology has led to the first unions of Reformed Christianity.

Reformed ecumenical theology is above all of a federalist type, since it seeks the union between the different separated communities by uniting among them. Thus, the "united churches (unierte Kirchen) in Germany were the state-sponsored unions between Reformed and Lutherans in the 19th century in mixed confessional territories. They are distinguished from the "Union Churches" by their top-down origin. (Unionskirchen) which arose as a consequence of the ecumenical movement born from the grassroots in the 20th century. Those alliances, born with popular opposition and separate from the Lutheran communities, are administrative unions that have achieved Eucharistic intercommunion among the different Protestant denominations.

Thus, the Reformed Churches in Europe took an essential step in the Leuenberg Concord of 1973, between which there is doctrinal and Eucharistic communion. Therefore, a Calvinist can receive communion in a Lutheran Community, and vice versa. The Lutheran theologian Oscar Cullmann (1902-1999), on the other hand, proposed the formula of "reconciled diversity", which is widely accepted in ecumenical circles. This proposal promotes unity without compromising one's own identity.