In the twentieth century, two theological treatises (leaving aside exegesis) have claimed to take over all theology. One is Fundamental Theology, because it claimed to be the justification of all matters of theology. The other, more minority, is Eschatology, when it defends that the whole Christian message is and must be eschatological. These approaches are quite antithetical. The claim of Fundamental Theology comes from the demands of reason, sometimes from academic reason. That of Eschatology, on the other hand, has a mainly theological inspiration. The first can err on the side of rationalism. The second, in its extremes, can point towards the utopian. This leads to the conclusion that they are needed to compensate each other.

Jesus Christ, the center of Eschatology

Eschatology is truly all-encompassing, because Christ himself presented his Gospel announcing the Kingdom to come. And also because the essence of Christianity, as Guardini says, is a person, Jesus Christ. But Jesus Christ in his fullness, and therefore resurrected. We live in tension towards the Parousia. And both in the Liturgy and in Christian action: we hope that the Lord will come now and at the end.

Some Protestant theologians emphasized that theology had to focus on the resurrected Jesus Christ (Karl Barth), and some made it concrete for eschatology (Althaus, Die lezten Dinge). Jesus Christ is the cause, the model and the foretaste of the human being in his fullness, as St. Paul shows.

Catholic manuals had divided eschatology into two parts: individual and final. In the first, they dealt with the problem of death (with the problem, perhaps, of the separated soul), judgment and the three possible states (heaven, hell and purgatory), sometimes adding a reflection on beatitude. In the second part, the final eschatology, they dealt with the second coming of Christ with its signs, the resurrection of the bodies and the new heavens and the new earth. Since these topics were more mysterious, it was a kind of appendix. Eschatology was centered on the end of each person. It was even asked whether the resurrection of the bodies added anything, and it was answered that a certain accidental glory. This contrasted with the idea that the resurrection of Christ is the essential event of Christianity and must be the center of eschatology.

Inspirations from Scripture

Many points highlighted by the Exegesis contributed in the same line. First of all, of course, the centrality of Christ. Then, the fact that Christ's preaching was eschatological from the beginning: he announced a Kingdom, whose leaven in this world is the Church. This gives an eschatological tone to the whole Christian proclamation and to all its history.

And it is not primarily an individual matter, but is realized in the Body of Christ in history, which is the Church. First in Jesus Christ, who "he rose from the dead as the firstfruits of them that slept." (1 Cor 15:20) and in this movement he drags his mystical Body and even the whole of creation, "who waits with ardent longing for the manifestation of the sons of God." (Rom 8:19). The revelation of God is, at the same time, the history of the Covenant, the history of salvation and also the history of the Kingdom. The Kingdom (with Christ at the center) is the great theme of eschatology and runs through the entire history of salvation.

Patristic and liturgical endorsements

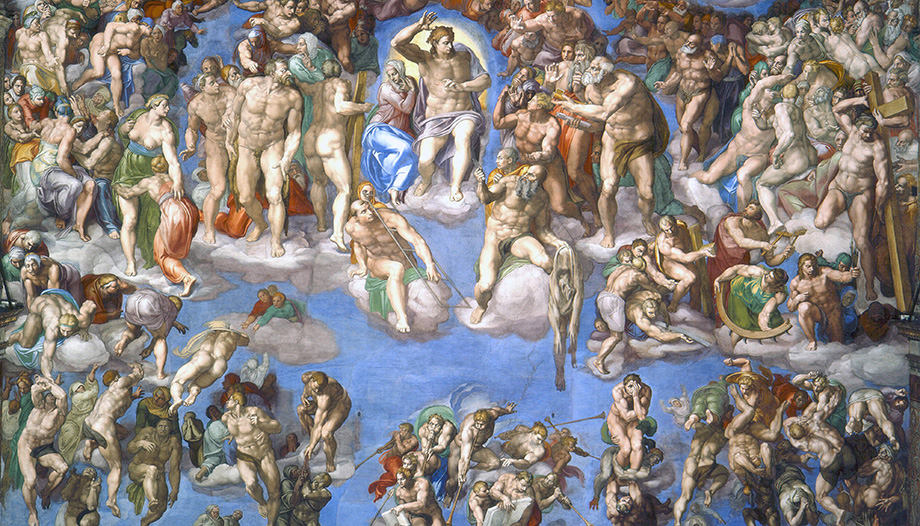

It was necessary to turn the treatise around: to begin with the resurrection of Christ, the first fruits, promise and cause of our resurrection; to speak of the history of salvation or of the Kingdom, and of the realization of the Church; and to give the whole Christian message and all theology this eschatological tension. Moreover, it is eminently expressed in the Liturgy, in every Eucharist, where the Lord's Passover is renewed until he returns. And in the liturgical year, from Advent to the last week of Ordinary Time, the second coming of Christ (Christ the King and Judge of history).

The contact between eschatology and liturgy was very enriching for both treatises. In reality, these relationships, now rediscovered, were already present in the Fathers of the Church. It was yet another manifestation of a common effect in the history of theology. Scholasticism had focused on studying the reality of things with the ontology inherited from Aristotle; the separated soul, contemplation, the condition of the resurrected bodies, also the "res" of the sacraments or of the Church as a social reality. That was his contribution. But he had no method to deal with the symbolic dimension. That was his oversight. By reconnecting with patristic theology (and also with Eastern theology, which is patristic by tradition) the approaches were renewed.

A novelty: the theology of hope

Another inspiration came from a completely different direction. Already the great Russian Christian intellectual Nicolai Berdiaev (1874-1948) had warned that Marxism is a kind of Christian heresy and that it had secularized his hope, promising a heaven on earth. A critical Marxist thinker, Ernst Bloch (1885-1977), noted precisely this in his voluminous essay The hope principle (1949). And he identified hope as the fundamental impulse of human life, which needs a future. Or even it is future, because it has to be fulfilled as a person and, above all, as a society (which is permanent). In this sense, it is not a matter of being, but of becoming. That is why hope and, to that same extent, utopia as a goal are the keys to being human.

The idea impressed a then young Protestant theologian, Jürgen Moltmann, who reviewed the book and discussed it with Bloch. The criticism that could be made of Bloch was obvious: hope is indeed the great motor of human psychology; but the Kingdom on earth is impossible: because neither death nor human limitations and failures can be overcome. Apart from the fact that all personal hope really disappears in order to immolate itself for the benefit of a social kingdom. But no matter how much is done, it is impossible to pass in this world from facticity to transcendence. Here it is always to be done, and we never get out of it, no matter how much we improve. With all the paradoxes that can come, moreover, about what it really means to improve.

But it was clear that Bloch was quite right. Hope is a driving force, the human being is hope. Secular hope has no credible goal, but Christian hope does. Gathering the inspirations we have mentioned and Bloch's challenge, Moltmann built up his Theology of hope (1966). And it had a great impact. It became clear that an eschatology is, in the end, a theology of hope, and vice versa. Hope was no longer the little sister of the other two virtues, as Péguy had poeticized (The portico of the mystery of the second virtue).

Moltmann has always been a man of easy words and great perspectives, but perhaps he has the opposite problem to scholasticism. In the former, attention to reality led to disregarding the symbolic. Here, sometimes, attention to the symbolic can lead to detachment from reality. That is what tends to mythology... The resurrection of Christ is real and not just a wait in the future where it has to be revealed.

The place of utopia

Among other things, the "theology of hope" posed the role of utopias as the driving force of human history. Precisely when Marxism had spread as a planetary ideology, when it had achieved various symbioses with Christian thought and when it had already become clear that it was not heaven. It would be one of the inspirations of Metz's theology of politics and liberation theology.

We need utopias, a certain Christian left will later nostalgically repeat, trying to justify a rather imperfect (and in many cases, criminal) past. But the utopia of Thomas More, which was the first, killed no one. And the Marxist one, many millions. Hence the postmodern reaction: we do not want grand narratives, which are very dangerous. The management of utopia requires discernment, but, above all, a thorough acceptance of the great moral principle that the utopian end does not justify the means; one cannot do anything in the name of utopia.

The Joseph Ratzinger Manual

With all this ferment of ideas, the then theologian and later Pope taught in Regensburg, among other subjects, eschatology. And he composed a small handbook (1977) with many intelligent and well-judged things. As he points out in the prologue, the manual has two concerns. On the one hand, it welcomes the endeavor to re-center eschatology in Christ, the thrust of the theology of hope, and discerns about its political and historical consequences. It also qualifies the idea that death is a moment of fullness, as Rahner had wanted to present it; because, rather, the experience is the opposite.

But it contains a remarkable novelty. It deals with the theme of the separate soul, which is difficult to present in our modern scientific context. It is helped by the inspiration of the dialogical philosophy of Ebner and Martin Buber, who formulates it with more persuasive force. From a Christian point of view, the human being is a being made by God for a loving relationship with Him forever. This is the theological foundation for understanding the survival of persons (of the soul) beyond death. It does not depend on the current plausibility of the ancient demonstrations of the soul or Plato's view. The Christian message has its own basis in this "dialogical personalism", which also allows us to delve into what it means to be a person. This theme, which has already been pointed out in the Introduction to Christianity, was a beautiful contribution of Joseph Ratzinger's manual, although it is not his original. But it gave it strength and diffusion.

The problems of the separated soul

Actually, the state of the separated soul between death and resurrection is a complex question. St. Thomas Aquinas had seen it, and he has on it a quaestio disputata. There must be a survival because, otherwise, every resurrection, even that of Christ, would be a recreation. But that soul is deprived of the psychological resources of sensibility, and for that reason, its subjective time cannot be continuous like the time we live with the body. St. Thomas also saw this. Therefore, it is possible to think of a certain subjective proximity between the moment of death and the moment of resurrection. Some Catholic authors have identified the two moments (Greshake), but it is not possible, because there are intermediate events, such as the judgment and the relations of the communion of saints. But it is not possible to think with our experience, because the soul is already before God who works on it. It is not a natural survival but an eschatological situation.

Curiously, while the question of the separate soul is difficult to present to a rather materialistic public, the belief in reincarnation or metempsychosis has grown, by cultural osmosis of Buddhist or Hindu convictions. And it demands attention.

And the theology of history

Parallel to these developments in eschatology, the twentieth century saw abundant reflection on the theology of history, which has hardly interacted with the treatise, but deserves to be taken into account.

The thesis of the Jewish philosopher Karl Löwitz on Augustine's theology of history and his essays on history and salvation, and on the meaning of history is well known. Also Berdiaev, cited above, has a remarkable essay on The meaning of history. And the great French historian Henri Irenée Marrou. On the other hand, we have The mystery of timeby Jean Mouroux. And the Mystery of historyby Jean Daniélou. And the Philosophy of historyJacques Maritain, who sees both good and evil growing at the same time. And the Theology of historyby Bruno Forte, whose theology is built precisely from history. And, on the other hand, that attention to utopianism, which Henri De Lubac, in his essay on The spiritual posterity of Joachim of Fiore. And Gilson, in The metamorphosis of the city of God.