The statement Dignitatis humanae of the Second Vatican Council confronted one of the great themes of the Church's dialogue with modernity, provoked the Lefebvrian schism and was the object of a precise discernment by Benedict XVI.

In 1972 Zhou Enlai, China's premier under Mao, managed to arrange a visit by U.S. President Richard Nixon. In an informal conversation, past and present revolutions were discussed and Zhou Enlai, who had been educated in Paris, was asked what he thought of the French revolution. He replied that "it was too early to tell". The anecdote, reported by the Financial Times, went around the world and became enshrined as an icon of the tempus lento of Chinese wisdom. Only much later did a diplomat acting as interpreter at the time clarify that Zhou Enlai was not referring to the revolution of 1789, but to that of May 1968.

With that, the anecdote lost its charm, but not its truth: both the revolution of 1789 and that of 1968 still operate on our culture and Christian life. The processes of individuals can last for decades, but those of culture can last for centuries.

Centuries lasted the process by which the Roman Empire was Christianized, and centuries by which the medieval European "nations" were constituted with the conversion and development of the barbarian, Germanic and Slavic peoples. Then, in two or three centuries, the nations were transformed into monarchical states, with borders fixed by wars and royal marriages. And since the 17th century, due to the ups and downs of the wars of religion, the desire grew for governments to be founded on rational bases and to better protect the rights of the people against the arbitrariness of the rulers: electing the rulers and dividing and limiting their powers.

Two stories and two separations

What was a utopia of parlor talk became policy with the independence of the United States (1775). Having to invent themselves, they chose to put it into practice. Precisely because a significant part of the American population came from dissidents who had fled or been expelled from confessional (Protestant) countries such as England and Germany, they agreed to honor God and respect their neighbors, but also that the state should not interfere at all in religious matters.

In France (1789), the process was completely different: at a time of economic and institutional crisis, enlightened and audacious minorities took over the state and brought about a transformation from above, overthrowing the monarchy and its supporters: the nobility and the Church with the traditional strata.

The United States was born with the churches voluntarily separated from the State. In France, the Church was part of the old national order, and the separation was an enormous tear in the national conscience forged over the centuries: the nation became a theoretically separate state, but practically aggressive, because it wanted to diminish the power of the Church, considered as a retrograde force opposed to progress. The same scheme, although less violent, would be followed in Spain, Italy and the American nations with independence.

Major objections

The Church, as an institution, was left wounded and on the defensive. It was very difficult to believe in the sincerity and honesty of a project where there seemed to be no room. And it was very difficult to believe that we were working for human rights when they were so easily violated for reasons of state.

Moreover, that the people constituted themselves as the source of all law and gave themselves the laws was hurtful to Christian ears. For God is the source of morality. Although it was no more than a rhetorical exaggeration, because in reality, most of the rights are not created, but are actually recognized. And it also hurt to impose freedom of worship where the Catholic unity of nations was broken, preferring the opinion or the whim of each one, and giving the same rights to all. This was considered an unacceptable relativism: truth does not have the same rights as error. This is how the great Popes of the 19th century expressed themselves.

Delayed effects of Modernity

In the Catholic conscience, the certainty of preserving the essence of the Christian nations has survived, with the consequent hurt and sadness for the losses and the nostalgia for the past. That is why it took a long time to enter the political game and, in a way, it never fully entered. The same nostalgia seemed to keep alive another impossible alternative.

This would have two negative effects: one, that traditional Catholics are accustomed to criticize or make moral judgments, but not to operate and defend themselves effectively in the democratic political game. The other is that they are not accustomed to evangelizing. For centuries they have worked in the instruction (catechism) and maintenance of worship, but there are hardly any channels, institutions or custom to evangelize in European countries. Preaching is done inside the churches, but not outside the churches. In the past, nations were constitutively Christian, and the state was expected to settle difficulties as a matter of law and order.

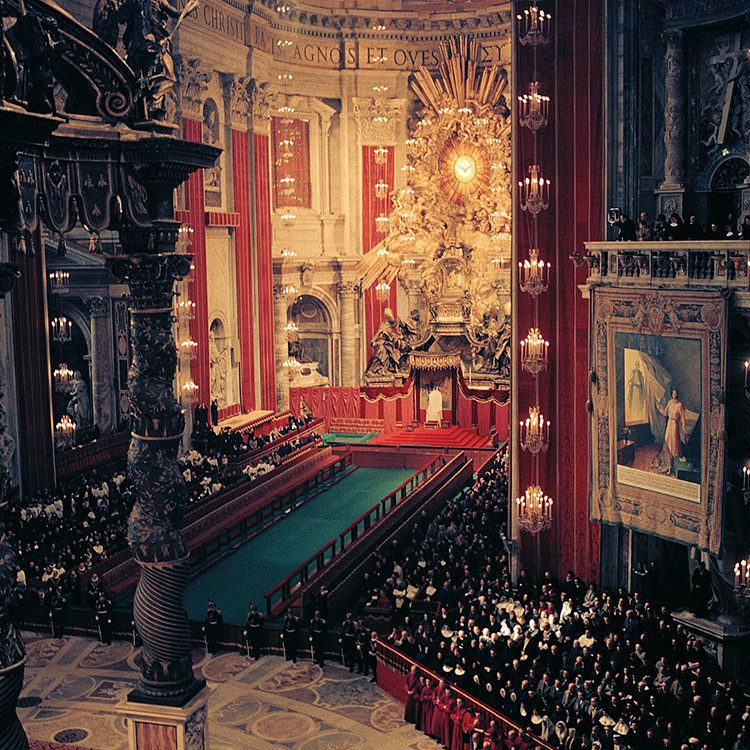

The purpose of the Council

Since he proposed it John XXIIIThe Council wanted to resituate the Church in the modern world and relaunch evangelization. It would also be an operation of centuries. The calmer and more conciliatory atmosphere of the post-war period (double post-war) facilitated dialogue, although an important part of the Church had remained under communist domination, where there was no dialogue at all.

The great efforts of the Council led to a renewal of the image of the Church as mystery (Lumen gentium), overcoming a historical, sociological or canonical vision that it also has. This was already very important to situate the Church in the modern world by elevation. The other great document Gaudium et spes However, the very history of the document's preparation led us to see that what the Church can say in the opinionated fields of family, economy, politics, education and culture is based on her revealed knowledge of the human being. An approach that the pontificate of St. John Paul II would insist on.

The tension of Dignitatis humanae

In this context, it is understandable that the effort to position the Church in the modern world also led to the discernment of conflicting issues, such as the acceptance of religious pluralism or freedom of conscience in the face of religious truth, and the separation of Church and State. This implied the acceptance of democracy as a valid system of political coexistence. And, incidentally, the renunciation of the aspiration for national religious unity as an objective of Christian action. If this were to happen, it would have to be by conviction, but not by imposition.

This change of aspirations and strategy had already been proposed by Jacques Maritain in Integral Humanism. And it was assumed by Christian politicians who had thought and entered the democratic game (Don Luigi Sturzo and the Italian and German Christian democracy).

The statements of Dignitatis humanae

The decree Dignitatis humanae begins by acknowledging the growing modern concern for freedom, also in the religious sphere. Then, he expresses the uniqueness of the Christian faith as revealed truth, and insists that "all men are obliged to seek the truth", but also "truth imposes itself only by the force of truth itself".. This means that the civil authority has to protect this process of religious freedom, granting a free exercise and without proscribing any legitimate exercise, as long as it does not disturb the social order.

Precisely because it is based on the moral principles of the person, it can affirm that "leaves intact the traditional Catholic doctrine concerning the moral duty of men and societies towards the true religion and the one Church of Christ.".

The document is very nuanced, but it was evident that there was, at least, a change of approach. Thus, and more severely, it was judged by several bishops and mainly by Marcel Lefebvre, who would write at length on the subject and would come to the conclusion that the doctrine of the Council departed from the established teaching of the Church and the Council had to be considered invalid. In the end, this would provoke a schism, and an echo that has not ceased to be heard and that also reaches many non schismatic Catholics.

Different experiences of the Church

It should be noted that in Dignitatis humane very different experiences converged

a) that of the bishops of the United States, where separation is one of the foundations of the State and the Catholic Church has enjoyed freedom from the beginning;

b) that of the bishops of the confessional Protestant states (Holland, German states, Scotland, Sweden, Norway, Finland...) and of England, where the division of Church and State allowed, since the middle of the 19th century, the normal development of the Catholic Church, previously forbidden and punished;

c) that of the bishops of the countries under communist domination, who saw in that declaration a defense of the Church based on fundamental rights of the person; among them, Karol Wojtyła;

d) could hardly speak (and today neither) those under Muslim rule, who would gain a lot if religious freedom were recognized in their countries;

e) in reality, the Catholic confessional countries were very few (and in regime of exception), above all, Spain, Portugal and some American nations to varying degrees. The rest lived with greater or lesser comfort and recognition in democratic regimes with religious freedom and separation.

Benedict XVI's Address to the Curia (2005)

On December 22, 2005, in his first year as pope, Benedict XVI addressed a very special Christmas greeting to the Roman Curia. He took advantage of the occasion to address the most important issues of the pontificate: the judgement on the interpretation of the Council, going beyond the rupturist adventures and at the same time the fundamentalist criticisms. It is a brilliant text.

At the beginning, Benedict XVI acknowledges that there has been a reform, but not a rupture. Without renouncing any of its principles, there has been a change of doctrinal approach. He refers, evidently, to the nuances required by the judgments of the Popes of the 19th century on liberalism, the separation of Church and State, and religious freedom.

Here are some phrases: "It was necessary to learn to recognize that, in these decisions, only the principles express the lasting aspect, remaining in the background and motivating the decision from within. On the other hand, the concrete forms are not equally permanent, since they depend on the historical situation and can therefore undergo changes. Thus, substantive decisions may remain valid, while the forms of their application to new contexts may change. For example, if freedom of religion is considered as an expression of man's inability to find the truth and is thus transformed into a canonization of relativism, then it is improperly shifted from social and historical necessity to the metaphysical level, and is thus deprived of its true meaning, with the consequence that it cannot be accepted by those who believe that man is capable of knowing the truth of God and is bound to that knowledge on the basis of the inner dignity of truth. On the contrary, something totally different is to consider freedom of religion as a necessity that derives from human coexistence, indeed, as an intrinsic consequence of the truth that cannot be imposed from outside, but that man must make it his own only through a process of conviction. The Second Vatican Council, recognizing and making its own, with the decree on religious freedom, an essential principle of the modern State, took up once again the deepest patrimony of the Church.". Remember also that, in the beginning, the Church, while recognizing the authority of the emperors and praying for them, defended its religious freedom against the pretensions of the Roman state. That is why so many martyrs died: "They also died for freedom of conscience and for the freedom to profess one's faith, a profession that no State can impose, but which can only be made one's own with the grace of God, in freedom of conscience." He concludes: "A missionary Church, aware that it has the duty to proclaim its message to all peoples, must necessarily be committed to the freedom of faith.".