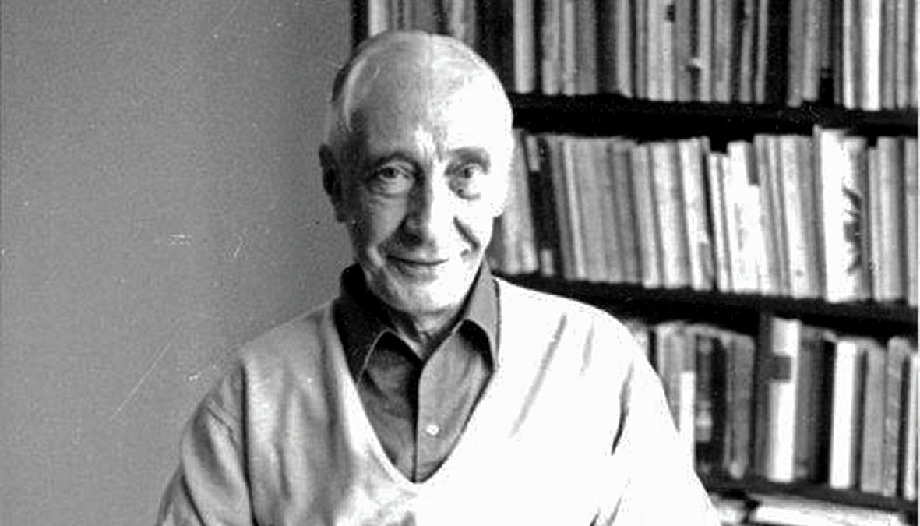

Pavlos or, in Paris, Paul Evdokimov (1900-1970) was born in St. Petersburg. From an ennobled family, his father was a brave and esteemed colonel, who was killed by a terrorist while trying to peacefully resolve a mutiny (1907). His mother, a noblewoman, took him to military school, and in the vacations to long retreats in monasteries. With the revolution (1917) the family retired to Kiev. And in 1918 Pavlos wanted to study theology, as a Christian reaction in times of trial, although it was very rare in his milieu (priests came from the lower strata). He participated for two years in the anti-revolutionary White Army. And, faced with imminent defeat, urged by his mother, he fled to Istanbul. There he survived as a cab driver, waiter and cook, a skill he retained.

The Paris years

In 1923, with the clothes on his back, he moved to Paris, like so many Russians. He worked nights at the Citroen and cleaning wagons. But he did a degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne. And when the Institute of Orthodox Theology was founded in Paris Saint Serge (1924) he enrolled for a degree in theology, which he completed in 1928. He dealt very closely with Berdiaev, a great Orthodox Christian thinker, and with Boulgakov, the founder of Saint Serge and dean of theology. His main sources are.

The contact with Western Christianity, its cathedrals, its monasteries, its libraries was an impressive enrichment for all, and in particular for Evdokimov. And it made them develop their Orthodox theology in dialogue with Catholics and also with Protestants and Jews. Saint Serge was a very relevant phenomenon of mutual theological influence and Evdokimov participated with enthusiasm in this exchange. Later, he would be a great promoter of spiritual and "pneumatic" (entrusted to the Holy Spirit) ecumenism. And since its foundation, he participated in the World Council of Churches (1948-1961) and was an observer at the Second Vatican Council.

War, welfare work and theses

He married Natacha Brun, an Italian teacher, half French and half Russian (Caucasian), in 1927 and they had two children. They lived near the Italian border until the Second World War. Again the catastrophe led him to go deeper into Christianity. And although his wife fell ill with cancer (and died in 1945), and he had to take care of everything, he undertook a thesis on the problem of evil in Dostoyevsky, which he published in 1942. The profound mystery of evil, as Boulgakov had transmitted to him, is that God is willing to abase himself (kenosis) and to suffer human freedom up to the redemptive cross. At the same time, inspired by the figure of Alyosha of The Brothers Karamazovdefines a lay spirituality that brings monastic contemplation into the midst of the world.

During the German occupation, he helped refugees (and Jews) with a Protestant organization (CIMADE). And when peace came, to displaced persons, in a shelter home. Then, until 1968, he directed the students' home that Cimade founded near Paris. He was a deeply Christian counselor among so many broken lives, and took a special interest in Orthodox youth. In addition, reflecting as a layman, he published a beautiful book on Marriage, sacrament of love (1944).

An intellectual turn and three final essays

His life changed when, in 1953, he began to teach in Saint Serge and when, in 1954, he remarried the daughter of a Japanese diplomat (half English), who was 25 years old. These are very intense years of spiritual and intellectual maturation. Shortly after his marriage, he published Women and the salvation of the world. And later a wide range of articles, Orthodoxy (1959), and an essay on Gogol and Dostoyevsky and the Descent into Hell (1961). He renews his study on marriage, The sacrament of love (1962). And he brings together many of his spiritual writings and his ideal of monasticism in the world in The ages of spiritual life (1964).

The last three years of his life, with the feeling that his time was running out, are dominated by his courses at the newly founded Higher Institute of Ecumenical Studies at the Institut Catholique de Paris (1967-1970). And by three panoramic essays. First, the most famous, The art of the icon. The theology of beautycompleted in 1967 and published in 1970; later, Christ in Russian thought (1969); y The Holy Spirit in the Orthodox tradition (1970). He dies unexpectedly, at night, on September 16, 1970. He has other minor works. His work is now difficult to find, although it is being republished, and has been quite pirated on the net.

The most remarkable thing about Evdokimov is that he is both a theological and spiritual author, who delves into the traditional themes of Orthodoxy, the contemplation of the glory of God, divinization, but also advances originally in the theology of marriage and priesthood, and in true ecumenism, with a very Eucharistic ecclesiology and linked to the action of the Holy Spirit. But he also advances originally in the theology of marriage and priesthood, and in true ecumenism, with a very eucharistic ecclesiology and linked to the action of the Holy Spirit. His colleague in Saint Serge and great friend, Olivier Clément, has given us the best spiritual portrait, which has been summarized here: Orient et Occident, Deux Passeurs, Vladimir Lossky, Paul Evdokimov (1985). "Passeurs" are border crossers (and smugglers). With their Parisian exile and their work, Lossky and Evdokimov, crossed the spiritual borders between the Christian East and West.

The context of the theology of beauty

The title of the book is The art of the icon, and the subtitle The theology of beauty. And it takes a lot of context to situate oneself in a deeper, more spiritual and transcendent subject than it may seem at first glance. To begin with, beauty is one of the names of God. The same divine essence radiates outwardly in the glory of creation, in the theophanies of the Old Testament (especially at Sinai); and fully, in the Transfiguration and Resurrection of Christ. Moreover, it comes as a reflection in the life of the saints, who, from their divinized soul, radiate the glory and the good odor of Christ; hence the halo that surrounds them in iconography.

Eastern theology, following the Byzantine theologian Gregory Palamas (14th century), has always distinguished (and canonized) the essence of God, incommunicable in itself, and the essence insofar as it is communicated to us, through two great "uncreated energies" (or acts ad extraThe Westerners would say): the creative action of God, which gives being; and the divinizing action (grace), which elevates the human being to the participation of the divine nature. And this is conceived as the eternal light that radiates over everything, which is also the "taboric light" of the Transfiguration, contemplated by the Apostles. This irradiation of the same divine essence is what divinizes us, making it an object of contemplation and a source of elevation and joy for those who love God. Vision of the veiled essence in this life and direct in the next, although always transcendent. It takes a transformation received from God, so that we can contemplate it with our mortal eyes. The contemplation of the Trinitarian essence of God is the most essential and characteristic of holiness, which thus participates in God.

Transmuted matter

God makes himself present in the world because he creates it, maintains it in being and, when he wishes, in history, he acts in it in an extraordinary and spectacular way. On the other hand, in addition to creating it, he makes himself present through grace, in the elevation of the human soul, and eminently in that of Christ.

But the great misfortune is that this world is fallen and broken by human sin. Because God wanted to confront with all its consequences human freedom, capable of sinning and turning away from its Creator. This moral fall produced an impressive cosmic ontological fall, which affects everything and needs divine salvation, which, however, will always respect human freedom. It will save by the attraction and power of redeeming love and not by coercion and violence.

Jesus Christ, made man, is "image of the divine substance" in the flesh, in his body. Subjected in this world to the condition of fallen nature, but announcing in his Transfiguration and anticipating in his Resurrection, the transmutation and salvation of all things to eternal glory, where there will be a "new heaven and a new earth": the universe transformed through the resurrection of Christ. Thus matter itself, which has been made by God and has integrated the Body of Christ, will participate in his glory and beauty.

The four parts of the book

The book is divided into four parts, which also draw on previous articles and lectures. The first describes "Beauty." with its theological sense, which we have advanced, resorting to the biblical and patristic vision of beauty and extending into the religious experience and into cultural and artistic expressions (with some unknowns about modern art).

The second is dedicated to "The sacred"The Church, as the transcendent sphere and presence of God in the world: in all its dimensions, in time, space and, in particular, in the temple.

The third is "The theology of the icon".. With its history in the Eastern tradition, the iconoclastic debates and the sanctions of the councils, the II of Nicaea (787) and the IV of Constantinople (860), which declares: "What the Gospel tells us through the Word, the icon announces through the colors and makes it present to us.".

The fourth is entitled "A Theology of Vision." and reviews and comments on some of the most famous icons and the main motifs or scenes. The chapter is presided over by a commentary on the icon of the Trinity of Roublev. It continues with the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir. And with the scenes of the Birth of the Lord, the Transfiguration, Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension. Then, Pentecost. And closes with the icon of Divine Wisdom (another name of God).

The theology of the icon

The theology of beauty as the name of God and divinizing energy (grace) and the theology of matter transmuted by the incarnation and glory of Christ form the framework of icon theology. But there is more.

First of all, a history, which has established, with spiritual experience, the forms of representation. To the uninitiated Westerner, it is surprising that the icons do not seek to be "beautiful". There is a stylization and an intentional austerity and seriousness, a distance, because we are dealing with something transcendent: not with an object of ordinary use, which we dominate, it is a way to enter into God. But, for that, it has to be born from above and not from below. This is also expressed in the "reverse perspective" and in the arrangement and sizes of figures and objects. It is about God's way of doing things, not ours.

An icon does not express the ingenuity of the artist, but the spirituality of the Church with its tradition. The artist can only contribute if he is deeply imbued with its spirit, if he prays and possesses the wisdom of faith. One paints by praying, so that one can pray. Then, in addition to respecting the traditional canons of representation (forms, colors, scenes, models), he can be truly creative, not with his own spirit, but with that of the Church, which is the Holy Spirit. For this reason, the icons are not usually signed. It is especially appreciated in the icon of the monk Roublev, at the same time revolutionary in its representation of the Trinity and traditional in its resources.

In section IV (Theology of presence) of Part III, explains: "For the East, the icon is one of the sacramentals, that of personal presence.". Icons are a holy and significant presence of the supernatural in the world and especially in the temple. A true, though veiled, irradiation of the divine glory and a foretaste of the recapitulation of all things in Christ, through the poor matter of our world, created by God and affected by sin. When it comes to a saint: "The icon bears witness to the presence of the person of the saint and his ministry of intercession and communion.".

"The icon is a simple wooden board, but it bases all its theophanic value on its participation in divine holiness: it contains nothing in itself, but becomes a reality of irradiation [...]. This theology of presence, affirmed in the rite of consecration, clearly distinguishes the icon from a painting with a religious theme, and it treats the dividing line.".

Other references

Much has been written, and happily, about icons. In the Eastern universe, the works of the Russian priest, engineer and thinker (and martyr) Pavel Florensky (1882-1937) are classic, on The inverted perspective and about The iconostasis. A theory of aesthetics.

It is worth mentioning The theology of the iconby Leonid Uspenski (1902-1987), an icon painter and thinker contemporary of Evdokimov, who, like him, was based in Paris, although he was linked to San Dionisiocreated by the Moscow patriarchate, and not to Saint Sergewhich had become independent in order to distance itself from communist rule.

In our Western and Catholic area, the artistic and theoretical work done by the Slovenian Jesuit Marco Ivan Rupník and his Aletti center, and by his mentor, the Czech Cardinal Tomáš Špidlík, should be highlighted.