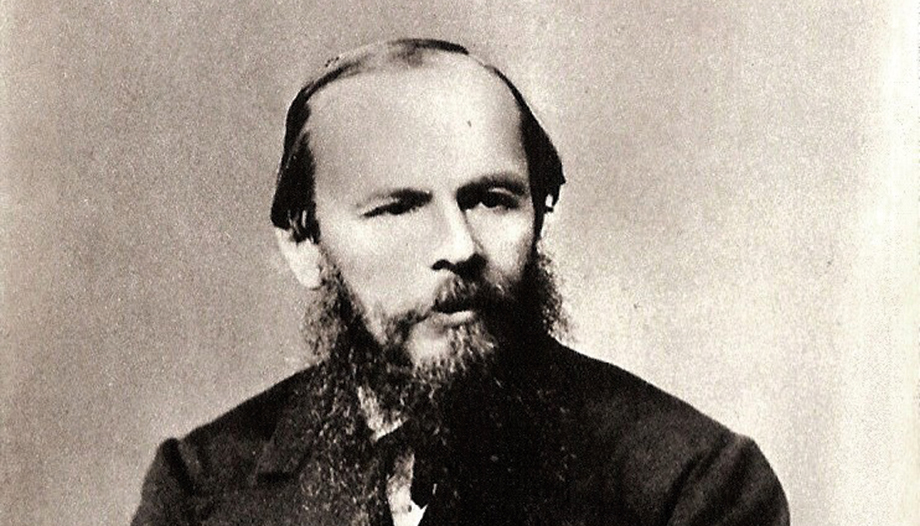

His life (1821-1881) can be considered his main novel, and the inspiration for all those he wrote. He was born and lived his childhood in a hospital for the poor, of which his father was the director. As a young man he let himself be carried away by gambling (a wound that never closed) and connected, like his friends, with the modern, enlightened, positivist, liberal and socialist ideas that came from the West (and that he would later hate) and fought with arrogance against the traditional world and the traditional Christian religion. Caught by the tsarist police in a "revolutionary" group (quite innocent in fact), he was condemned to death. After nine months in prison, his sentence was commuted to 4 years of hard labor in Siberia, followed by 5 years of service as a private in Kazakhstan.

Discovering the Russian people and faith

Ten years in contact with the lowest, besides childhood. But among those people and in those remote places, he discovered the immense Christian piety (not very enlightened) of the Russian people. Also the awareness of sin and, in many cases, the inability to overcome it.

There were all kinds, but also believers who accepted their sorrows and were merciful to others and to Dostoyevsky himself, who was so hard hit by fortune. He was converted. He became a supporter of the people and their love for the passion of Christ and his mercy for those who suffer. And he will feel opposed to those Western ideas that, with various formulas, want to build a new, enlightened and godless society. He thinks that these ideas come from Western Catholicism, which he detests (and does not know). Moreover, he shares the traditional idea that Russia is the Christian stronghold, after the Christian West broke away and fell into heresy and the Byzantine Empire was destroyed by Islam. It has the historical mission to bring the Gospel to the whole earth.

The recumbent Christ

He himself, as an epileptic, irascible and compulsive gambler, and always haunted by debts (because he supports many relatives), knows well the holes of freedom and its abysses. The same epileptic crises are moments of lucidity and liberation from so much burden.

In 1867, at the age of 46, he married (second marriage) a charming girl, who helped him write The player. And they spend a few months in Switzerland, always asking for advances for their works and eaten by debts (she pawns several times her wedding ring and her clothes).

A little daughter born there died two months later. And one day in the museum of Basel, she stumbled upon the recumbent Christ of Holbein, placed on a sheet, with the cadaverous skin, the traces of all the tortures, the wild eyes and the disjointed face. She never tires of looking at him (she tells about it in her diary). She knows that this is God's method, the extent of the defeat of good by sin, and the extent of love in redemption through suffering. It is the strength and also the scandal of faith.

Since 1867, works and personalities

These are the most fruitful years. There is a succession of works with their unforgettable characters.

In the same 1867, Crime and Punishmentwith the emancipated and "modern" Raskolnikov, the unfortunate drunkard Marmeladov and his daughter Sonia, the good soul, prostituted to support the family, who will redeem Raskolnikov.

In 1870, The idiotwith the candid and disconcerting Prince Mischkin, epileptic and good to the point of sacrifice. In 1871, the Demons o The demoniacsThe first of its kind, a true prophecy of the construction of a society without God. In 1875, The adolescentThe lesser known, where a boy learns about the struggle between good and evil in his father's life. In 1879, the masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazovwith a fantastic gallery of characters: the father, Fiodor, bourgeois, vulgar and carnal, and his three sons: the liberated and modern (and atheist) Ivan; Dimitri (Mitia) who, from the start, resembles his father; and Alyosha (Alexis) who wants to be a monk; and his spiritual master, the venerable monk Zosima, and the fourth and unrecognized bastard son (Smerdiakov), with all the seeds of evil?

But all the characters carry inside or stumble outside the drama of evil.

Theological impact

Since the end of the 19th century, Dostoyevsky's work was received. And it stunned so many leading theologians. Among the Protestants, Karl Barth stands out. Among the Orthodox, the group of Christian intellectuals who emigrated to Paris with the Russian Revolution: the thinkers Berdiaev and Chestov. The theologians: Boulgakov, Florovsky, and especially Evdokimov, who will deeply study evil in his work.

Instead, traditional orthodox theology did not connect with him. Among Catholics, many, but it is worth focusing on the masters: Guardini, De Lubac and Charles Moeller.

Romano Guardini and the characters

Guardini was very interested in Dostoyevsky's work at a very early age, when he began his courses on the Weltanschauung Christian in Berlin. And in 1930, he took advantage of some conferences to put his ideas in order: Dostoyevsky's religious universe (Emecé, Buenos Aires 1954). He is focused on the characters and shows an enviable mastery of the work as a whole. In his own words: "The seven chapters that make up this book deal with the religious element and its problematics in Dostoyevsky's work considered through his five great creations: Crime and punishment, The idiot, Demons, A teenager, y The Brothers Karamazov [...]. Ultimately all of Dostoevsky's characters are determined by forces and elements of a religious order." (11). "He is a creator of human personalities of such greatness that it is only possible to measure it little by little." (256).

Study first the people, with their simple piety (and a bit of paganism) and especially those little women full of compassion. "For Dostoevsky, as for all the great Romantics, the word 'people' awakens resonances of veneration." (17). In contrast to Western "society", which has lost its roots in nature, tradition and Christianity. The people is the natural unity and not the individual. It venerates its saints, its monks, its icons and leads a hard life without complaint. Chapter 2 follows this meekness and two Sonias, fantastic female figures; the first one, the wife of the "Russian pilgrim" Makar (of The adolescent). The second, from Crime and punishmentperhaps the most moving character of all. In Chapter 3, we study the religious, the pilgrim Makar, and the staretz Zósima (from The Karamozov Brothers), a good and wise man who knows how to lead souls.

The entire chapter 4 is centered on Alyoscha, the Karamazovs' youngest brother. He wants to be a monk and looks like an angel. Although his brother Ivan, in a memorable conversation, warns him that he is also a Karamazov and that in his blood there will be storms. And there are, because his candor is proven. He admires Zosima, but, in the end, he does not measure up to her.

Chapter 5, entitled Rebellionstudies the surprisingly long and Legend of the Grand InquisitorIt is a mistake to leave to people a freedom with which they can sin (in this God is wrong); it is enough to keep them satisfied. The moderns also want to supplant God and be more reasonable, dispensing with the madness of sin and the cross. Among them Ivan Karamazov, also discussed here. This connects with chapter 6, dedicated to "impiety", mainly in The demoniacsand the contrast between the simple unbeliever (Kirilov) and the one who, deep down, hates God and those who remind him of Him (Stavrogrin). Finally (chap. 7), we study the christic figure of Prince Mischkin, doomed to failure.

The drama of atheistic humanism

This very famous work by De Lubac was conceived during the Second World War, in the face of the disaster caused by atheistic cultures (Nazism and Communism) and the overbearing (and sometimes insolent) atheism of radicals and positivists in politics and culture. The thesis of the book, inspired or at least illustrated by Dostoyevsky, is: "It is not true that man [...] cannot organize the earth without God. What is true is that without God, he cannot, in the end, do more than organize it against man." (Encuentro, Madrid 1990, 11).

It is divided into three parts. In the first he contrasts Nietzsche with Kierkegaard. Both existentialists and (like Dostoyevsky) angry at bourgeois falsehood, but Kierkegaard finds his authenticity in submitting to God and Nietzsche in dispensing with Him. Kierkegaard knows he needs to be forgiven. And Nietzsche assumes the freedom to live on his own, because God is a limit and, moreover, a fiction. We are alone. The second part explains Comte and his positivist pretension (to the point of ridicule).

The third part bears the significant title Dostoyevsky prophet. He compares him, first, with Nietzsche. Then comes a marvelous chapter (III,2), which is The bankruptcy of atheism. The tremendous holes in the atheist project, with three suggestive points: The man Godwhich is the project to replace God. The Tower of Babela construction "not to go up to heaven, but to bring it down to earth". (229): there are two formulas, the realism of the Grand Inquisitor (all quiet) and the romanticism of utopian socialisms, which become criminal (demonic) when they are tried (The demoniacs). The third point is The Crystal Palace; "this palace is the universe of reason, as concluded by modern science and philosophy." (238). They want to be only natural and they cannot, because nature is wounded and created and destined for God.

Greek wisdom and Christian paradox

It is a brilliant book by the Leuven priest and professor Charles Moeller, famous for his 8 volumes of Twentieth century literature and Christianity. It occurred to him to compare how the classical world, Greek and Roman, and the Christian world deal with the great existential questions. And he chose great literary works to illustrate it. First, sin. Actually unknown in classical literature, where the protagonists are surprised by the battles that the gods give in them (the passions). In contrast, Shakespeare's and Dostoyevsky's analyses identify freedom and its downfalls and limits. In Dostoyevsky, he studies the differences between the sin of weakness (Marmeladov) and the sin of the gods (Marmeladov). "sin against the light" (Ivan K., Stavrogin).

In the second part, The problem of suffering. The classics only knew how to respond by maintaining the type with the greatest possible dignity. Christians have been introduced in their sense by the cross of Christ, scandalous to reason. That is why he studies The elevation by suffering in Shakespeare and Dostoyevsky: "betrothal with pain", "redemptive suffering". y "the joy of the cross". It is the world of the suffering righteous, of the "humiliated and offended"of the scandalous victory of evil over good. But it is "Christ crucified the one who explains the paradox of the suffering righteous, a God who humbles Himself and descends to man." (183).

The beauty that will save the world

One of Dostoyevsky's considerations will also end up having an immense theological impact. It is the question addressed to Prince Mischkin: "Is it true, Prince, that you once said that beauty will save the world?". He does not answer with words, but he answers with his life. The beauty that saves is the beauty of love that leads to redemptive sacrifice.

Blondel had warned that, in modern culture, the way of cosmological knowledge has been blinded to reach God, and also the moral way, by the study of human freedom (the moral good). There remains the path of beauty. Von Balthasar also raises this point in Only love is worthy of faith. And he tries to do so in all his work, which aims to show the extent to which the kenosis of Christ, out of love, is the true beauty and true sign of God in this world, prolonged in the exercise of charity.

In his Nobel Prize speech (1972), Solzhenitsyn, with the tragedies of the 20th century behind him, recalled: "Only beauty will save the world". "The ancient trinity of Truth, Goodness and Beauty is not simply an empty, faded formula as we thought in the days of our pretentious, materialistic youth. If the tops of these three trees converge as the scholastics claimed, if the too obvious, too direct systems of Truth and Goodness are crushed, cut off, prevented from breaking through, then, perhaps, the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected offshoots of beauty will emerge and ascend to the same place [...]. Then, Dostoyevsky's remark, 'Beauty will save the world,' will not be a phrase just blurted out but a prophecy. After all, it was given to him to see beyond, being, as he was, a portentously enlightened man."