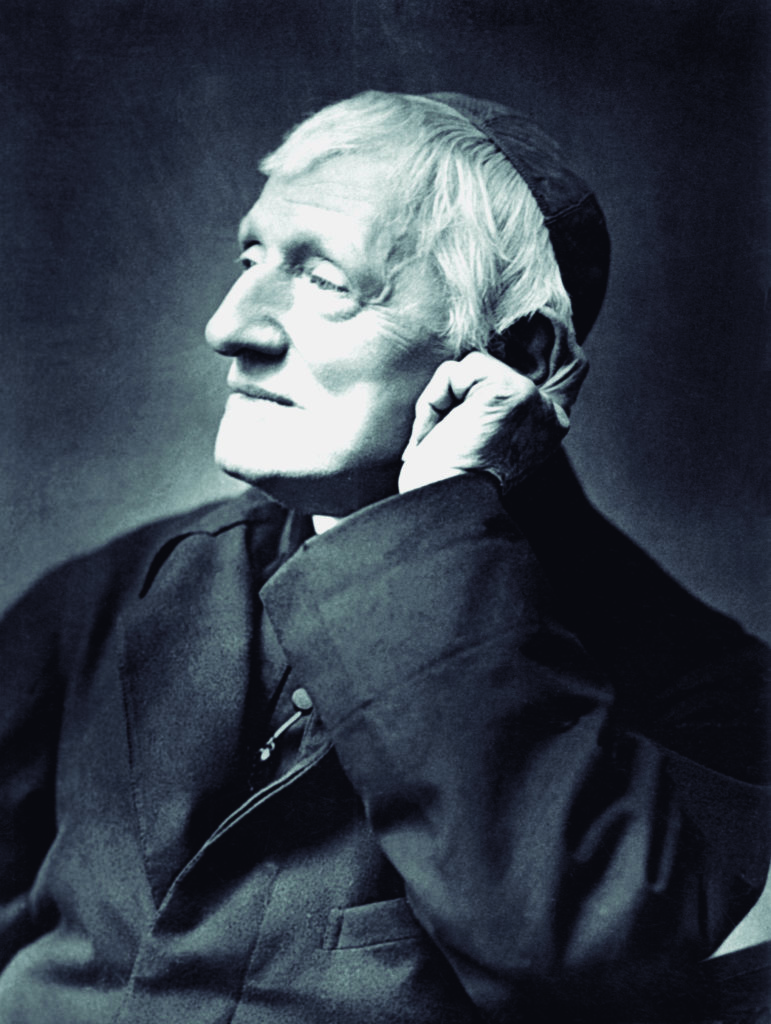

As his biographers, and indeed anyone who has looked at the English cardinal's life or writings, know, Newman's temperament and thought are so rich that it is impossible to label him.

The multifaceted figure of John H. Newman

Put positively, Newman brings together in himself such a variety of aspects and sensibilities that he is attractive to people of very diverse ideas and characters. And this is something that is very convenient for the world and the Church today: models of Christianity that flee from pigeonholing or simplifying classifications, capable of uniting people and reconciling ideas, who rigorously and tenaciously seek the truth -without adjectives or concessions- and at the same time are lovers of sincere, warm and reflective dialogue.

That is John Henry Newman. Without a doubt, a figure sui generis. He cannot exactly qualify as a philosopher nor as a theologian. Nor was he only a writer or a thinker. Nor was he only an apologist or a man of action. He lived halfway between shepherd and hermit. He was a man of this world with the soul of another. Newman was all of these things at once. And precisely for that reason, a saint from head to toe, of the world and for the world from the other world.

Yet, if there is one thing that comes to mind when the name of John Henry Newman is evoked, it is the idea of a person who personally and directly seeks the truth; and a person who allows himself to be compromised by it, for there he does not let the Will of God, Absolute Truth, be seen.

Coherent Christians

This love for the truth led him, apart from the acquisition of a broad humanistic culture at Oxford University, to the careful reading of the Fathers of the Church, while he was already a clergyman, but still an Anglican priest. This treasure of Christian wisdom, absorbed in its origins, would influence all his later life and preaching.

It was precisely then that he began to perceive his mission to revitalize the Anglican Christianity of his time. And he began to fulfill it by preaching. From that period come his best known sermons: the Parish sermons and, prepared as essays for a more cultured audience, the University sermons. All these sermons can be read in a Catholic key, and many consider them to be the masterpiece of Newman's entire production.

Newman would consider this period as the germ of what would later be called the "Oxford Movement", with which he had a double objective: to show that the Anglican Church was the legitimate and direct descendant of the apostolic Church, as opposed to the deviant Church of Rome; and to raise the ascetic and spiritual level of the Anglican faithful, in the face of the danger of sliding towards Protestant subjectivism. However, this second task soon began to cause him difficulties, attracting upon him the accusation of "Anglo-Catholic".

The Oxford Movement formally began in July 1833, after a long and providential journey through the Mediterranean. These were years of intense preaching, study and publication. Newman was concerned about the truth, but also about the lack of coherence and commitment to it. The scandals of the incoherent Christians pained him, and in his sermons he sharply spurred the personal conscience of the parishioners. No one was indifferent to his persuasive and lively words. At the same time, the Tracts for the Times (a kind of pamphlet as an organ of expression of the Movement, written by the different members of the Movement).

The true Church

Newman sensed from a very young age the presence of God, both in his soul and in the background - as if behind a "veil," he liked to say - of the natural and human world around him. For him, God was undoubtedly everywhere. But he knew very well that Christ had founded a Church, and that in it he wanted to dwell especially and gather his children, to accompany them and to guide them. And until then he believed that this true Church was the Church of England, the Anglican Church.

However, in those years of the Oxford Movement Newman was increasingly assailed by the suspicion that the alleged deviations of the Roman Church were not so essential; and that, above all, the Catholic Church was more in continuity with the apostolic Church than the Church of England. In spite of this, at that time he tried to open a middle way between Protestantism and the Roman doctrine, which he expressed in his writing Via Media.

In fact, it can be said that almost all of Newman's life was a search for the true church. Inspired by his reading of the Fathers, Newman discovered that the genuine church has a dynamic and evolutionary character. Just as revelation is gradual, so is the development of the church. That is why he is no longer so surprised by the diversity of ritual forms (Roman or English), nor by the different ways of expressing and teaching doctrine, or by the progress of doctrine itself. He is also understanding better what it means that the church, as the Body of Christ, is incarnated. As such it needs a social organization, a system of doctrine, an institution. But, above all, it is constituted by the gift of grace that God offers to men. The priority is its spiritual reality. The church is the souls that compose it and that grace unites into an ecclesial body. Moreover, as incarnated in history, the church evolves in its forms and these, like its members, are fallible. And also for this reason all the Christian faithful - the laity, with its sensus fideliumno less than the clergy - are, with their faith and their witness of life, instruments of tradition.

As can be seen, this idea of the church, which Newman recognizes and emphasizes in the Catholic Church, was a precursor of the Second Vatican Council, and continues to be very illuminating in our day.

Personal faith

Like a new St. Augustine, Newman faces the step of definitively resolving his doubts and, above all, of translating his intellectual conviction into vital conversion. Newman himself describes in great detail, in his Apologia por vita suahis process of conversion. How his doubts and his inclination towards the Catholic Church are accentuated, and how his social life becomes more difficult. Such doubts begin to attract numerous suspicions and antipathies, while in his spirit boil with all intensity the problems that have made Newman famous: obedience to his own conscience in the search for truth and how to adhere to it with all the certainty that is possible.

The straw that broke the camel's back on this tension was the publication of the Tract 90which was officially criticized by the Anglican hierarchy and led to the end of these publications. As a result of this incident, he retired definitively to Littlemore (a small church that depended on Saint MaryOxford) with a small group of followers. There, in 1845, he embraced Catholicism and was received into the Catholic Church, receiving priestly ordination two years later and joining the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, a congregation that he would spread in England.

In addition to its ApologiaNewman left us two other valuable writings that illustrate how he adhered to the full truth about the faith and the Church. They are the famous Letter to the Duke of Norfolk and of the Essay to contribute to a grammar of assent.. The first was written in response to accusations of double and opposite obedience - to the English civil authorities and to the Roman ecclesiastical authority. It constitutes a solemn defense of personal conscience (therein lies his famous "toast to conscience") and a defense of the legitimacy of being Catholic, obedient to the Pope, while being at the same time a faithful and exemplary English citizen. The EssayThe text, on the other hand, is a more extensive and academic text where he reflects on certainty and the possible ways in which one can assent to the truth; that is, on the framework that allows us to understand what it means to believe.

In the world and for the world

Newman's character was rather shy and reflective; even somewhat introverted, but resolute and bold when necessary. If we add to that his unwavering and priority commitment to the truth, it is easy to imagine that his life was a permanent swimming against the tide: against the general atmosphere hostile to Catholicism, against the liberal-Protestant current within Anglicanism, against the incomprehension of his Anglican friends or against a certain Catholic clericalism. But Newman did not shrink from these difficulties, and in this he constitutes another example for our times. We can see this love of the world, for which he strove to improve, in three areas: the university, the laity and his friends.

The university

Since joining the Trinity College from the University of Oxford at the age of 16, until his appointment as a fellow fee for the same college in 1878, Newman was a university man to the core. He would always remember his Oxford years with special pleasure, and all his writings reflect the measured and rigorous style of an intellectual, at the same time academic and friendly. His fame in this regard must have been notorious for the Irish bishops to ask him to promote the Catholic University of Ireland (now the Catholic University of Ireland). Students’ Union President.), with the idea of offering young Irish people a Catholic-inspired center of higher education, on a par with and as a counterweight to the prestige of the Anglican universities in the United Kingdom.

Although he devoted only four years to this task as rector of the nascent university, a series of lectures he published under the title "The University's Future" are preserved from that time. The idea of the university. This book is an essential reference on the mission of the university, the role of theology in the university disciplines as a whole, and various questions about university work in general and in some particular areas.

The laity

One of these ideas about the university is his respect and appreciation for the legitimate autonomy of human knowledge. Newman's civil formation kept him far from the clericalism or confessionalism present, on the other hand, in certain Catholic circles (and certainly not less so in Anglican ones). It is primarily the laity who must incarnate and transmit the Christian spirit in the very heart of the world. On a personal level, Newman exhorted Irish students to cultivate the human virtues of a responsible student, and of a gentlemanly gentleman, in order to cultivate upon them the supernatural Christian virtues. And the intense dedication and care in the very preparation of his Parish sermons gives an idea of how much he appreciated the formation of lay parishioners.

Although the fruitfulness of this vision would only be manifested to the universal Church more than a century later, at Vatican II, this stance earned Newman the intellectual respect of his intellectual colleagues and of all the people, as would become more than evident at the end of his life. Newman felt himself fully a citizen of the academic community and of British society, but - or rather, precisely because of that - he felt an equal need to inform and enlighten them with a higher truth than that of this world.

Friends

Newman's numerous letters to his friends, and the very tone of his sermons, reveal an enormously endearing and even exquisitely sensitive character. This gave him great consolations and pleasant moments, but no less bitterness and suffering. At that time it was not easy to understand the passage from the Anglican to the Catholic Church. National history and tradition weighed heavily. An example of this is that it was not until 1829 that English Catholics regained their religious freedom.

His famous sermon Separation from friends (included in volume 7 of Sermons parish), the last one preached as an Anglican at St. Mary's vicarage college church, reflects the real heartbreak he suffered as he followed his conscience and saw how that decision opened a gulf between him and his friends, and even his family. Yet his decision was firm. In the last words of that sermon he said: "Pray [for me] that I may know how to recognize God's will in everything and that at all times I may be ready to carry it out.".

However, Newman did not let his love for his friends and for English society as a whole die out. On the contrary, he did not cease to nourish it. In fact, he devoted a great deal of his already converted life to trying to win back friends, to explain his conversion and to defend himself against accusations and polemics. And surprisingly, he succeeded. He won back all his friends (some of them took him 30 years). Public opinion changed to such an extent that after his death more than 15,000 people bade him farewell in the streets of Birmingham; and at the funeral held at the Brompton Oratory The event was attended by thousands of Catholics and Anglicans from England, Wales, Ireland and Scotland.

Saint Newman

But anyone who saw in Newman only an intellectual whose life would be difficult for anyone to imitate would be mistaken. Newman was a normal person, transparent and simple. And while many of his works reflect an uncommon intelligence, others - letters and diaries as well - show his closeness. Moreover, Newman's path to truth was not a merely scholarly itinerary, but always guided by God, who is Truth. But in addition to Truth, God is Love.

Newman's life is steeped in the presence of God, in books and in nature, in every person and in every community. He knew how to see God in everything. That is why his search for truth was nothing but the search for God; that is why he found him in the great and the small, in the sublime and the ordinary.

It is understood that one of his main convictions was that the search for and transmission of truth was only possible through the human person in his integrity: in body and in soul; with head and with heart; in intimacy and in company; with teaching and with good and warm example; through study and in living together with friends, family or religious community. His opening of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in Birmingham, and later in London, is further proof of this.

As for preaching, a certain rigor in his teaching - necessary then, and always, to awaken a slumbering and lukewarm Christian life - is balanced by inspirations of a tender and profound devotion, and by his keen penetration of the scenes of Scripture.

In short, Newman knew how to transmit his love for the truth and for people in a way that was, for many, miraculous. By the end of his life, Newman had won the affection and admiration of the entire United Kingdom. On the day of his funeral, the Irish newspaper The Cork Examiner published referring to the aforementioned funeral procession: "Cardinal Newman descends into the grave as people of every creed and walk of life pay him homage, for he is recognized by all as the righteous man turned saint.".

Pope Leo XIII affirmed that Newman, more than any other, had changed the attitude of non-Catholics towards Catholics. In addition, he opened a door and walked a path along which, inspired by his figure and thought, the wave of converts of the first half of the 20th century followed: Oscar Wilde (on his deathbed), Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Graham Green, Evelyn Waugh, etc.

The motto that Newman chose for his cardinal's coat of arms reads. "Cor ad cor loquitur" (the heart speaks to the heart). Thus Newman listened to the voice of truth, of God. Thus he preached and conversed with those near and far. So too will the new saint speak to so many people of our day. n