Mark Giszczak, Ph.D., teaches classes at the Augustine Institute, but he also writes books and gives talks about the Bible. He thinks that "we need to get to know God, read his word and let ourselves be changed and impacted by it". At the same time, "we have to recognize that we will never know everything."

– Supernatural Holy Bible Do we know if the texts are accurate? How does inclusive language impact translations? What are the challenges to capturing the authentic message of the Word? In this interview with Omnes, Dr. Giszczak addresses these and other questions.

What is the biggest challenge now facing Bible translators?

- In my book on Bible translation I talk about the challenge of inclusive language, which has been a very important topic of discussion over the last fifty years. There has been a real shift in the way we think about men and women, about roles, and language has a lot to do with it.

In Bible translation, some translators have gone in the direction of trying to make the Bible as inclusive as possible. And others have taken a different, more conservative approach. They say we should make as many things as we can as inclusive as possible, but if the biblical text is gendered, then we should translate it as it is.

This becomes a kind of dialogue about the right way to translate. And I think as the conversation around genre continues to change, Bible translators will continue to have to reflect on the right approach.

On the one hand, there is a kind of tendency to yield to whatever the culture is doing at the time. On the other, there is a tendency to resist the culture. I think the right way to go is somewhere in between. Christian translators should resist the idea that contemporary culture can rewrite biblical anthropology. But, on the other hand, I think we must translate in a way that communicates with contemporary culture.

How can translators make sure that they do not miss the true meaning of what God meant?

- In certain religious traditions they solved this problem by not translating, the Koran is famous for that. In Islam, if you really want to be a scholar of the religion, you have to study Arabic and read the Koran in the original language. Something similar happens in Judaism. In Christianity, however, we have a tradition of translating the Scriptures.

This actually goes back to early Judaism. In Greek and Roman times, around the time of Jesus, most Jews did not know Hebrew, many of them spoke Greek. The Old Testament was translated into Greek for them and that is the version of the Old Testament that the early Christians adopted, because most of them also spoke Greek.

When the Church began to evangelize, many Christians spoke Latin. Therefore, it was necessary to have both a Greek and a Latin version of the Bible. This meant that our sacred text existed in several languages and always faced the problem of translation.

We have inherited this problem in a special way in our time. Today Christianity is a global phenomenon and there are many languages into which the Bible needs to be translated.

All translators face problems because, in order to make a good translation, the translator has to understand the original languages and cultures very well, but also has to be a good student of the target language, to understand how the meaning of one language family can be translated or transferred to a different one.

There are two basic approaches to Bible translation. One is dynamic (or functional) equivalence and the other is word-for-word (or formal) equivalence. Dynamic equivalence can be very helpful in getting as many Bible translations done as quickly as possible, but the theory of dynamic equivalence is inaccurate by design, it is meant to be very flexible. And when it comes to theological ideas and the teaching and tradition of the Church, it is very important that our translations convey as carefully as possible what God intends to teach us in the sacred text.

This is where the Vatican changed its policy on translation. We can see this in a 2001 document, "Liturgiam authenticamThe Bible is a "Bible translator," which promotes fidelity and accuracy in Bible translation. It says that one should strive to maintain fidelity to the original text. But also strive to explain the text in a way that is understandable to speakers of the target language.

It is a constant tension in Bible translation. Are you going to focus primarily on the text and be very accurate, or are you going to focus more on the audience and exactly how they are going to understand it? Different translations and different translators have adopted different theories depending on how they are going to answer that question.

It seems that language is now a volatile thing that changes rapidly. Also, people are easily offended when others use certain words. This is a challenge for translators, how can they deal with it?

- Language has always been political, because it's the way we communicate ideas and concepts. And there are things in the Bible that offend people, and depending on what era you live in, people will be offended by different things. I think as catechists and evangelists we can do our best to explain the ideas of the Bible in the most inoffensive way possible. But it is true that the language of the Bible is sacred and therefore unalterable.

An example of this is that God reveals himself as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. We know theologically that God has no gender, but the fact that we know that theological idea does not allow us to change the way God reveals himself. For example, some Christians have experimented with referring to God as Mother or the Holy Spirit as "she," and this kind of manipulation of biblical language is very dangerous. It runs the risk of completely undermining God's revelation to us.

If we start changing the principles of the Bible that we don't like, suddenly we are no longer students or disciples of the Bible, but in a way we are telling the Bible what it should teach us. This is a very risky position to take.

How do we know that the Bible we read today is the Bible that was written hundreds of years ago? How do we know that it has not been tampered with?

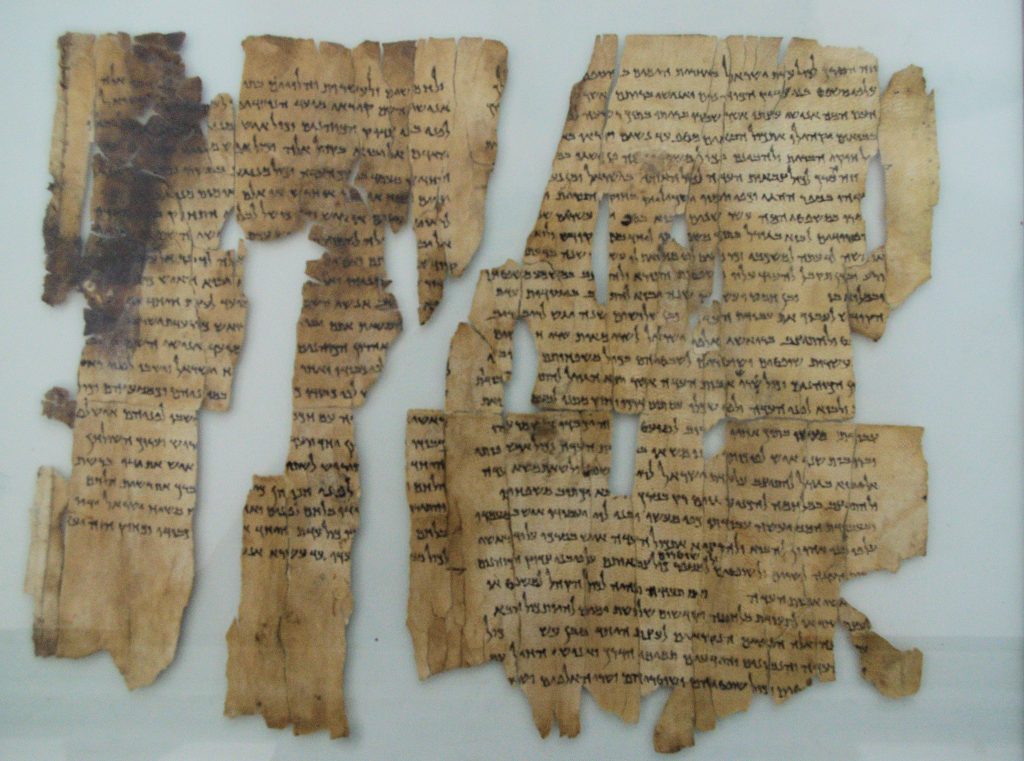

- This is a complex issue. In libraries all over the world we have ancient copies of the Holy Scriptures and many of them are fragmentary. Many of the earliest copies we have of the Bible come in small pieces, but some of the largest manuscripts we have are very old, from the time of Emperor Constantine.

As scholars have analyzed all the evidence of these fragments and manuscripts, they have been able to demonstrate that there is continuity over time. There are no major breaks in the chain of transmission from antiquity through medieval times and monasteries to modern libraries and translations.

The text of the New Testament, for example, has been examined in great detail by scholars. We are certain about it, about 98 % and 99 %. There are certain passages where it is not very clear what the original text was, but for the most part, 99 %, we know it is accurate.

Another major piece of evidence that has been useful is the Dead Sea Scrolls. Our earliest copies of the complete Hebrew Bible are quite late, around 900 A.D., but the Dead Sea Scrolls are dated around the time of Jesus. These scrolls verify that our copies of the Hebrew Bible are accurate. Now, it is true that some things have changed. The spelling conventions have changed and there are certain parts that are slightly different, what we call textual variation. But we have found, for example, a complete copy of the book of Isaiah, which has 66 chapters, and it matches our text of the Hebrew Bible. Thus, we can verify that the Jewish tradition of transmitting the Hebrew text really preserved the original text with great accuracy.

How can we explain the different interpretations that each of us gives to the texts and make sure that they do not divert us from the true teachings of the Church?

- God, in his wisdom, did not create us all exactly alike. Each of us has our own personality, characteristics and life history. God, in his wisdom and truth, is able to reach each of us in our own individuality.

Thus, whether we think of the difference between one Pope and another, or the differences between the homily of one priest and that of another on the same Sunday Gospel, each person, in his or her own individuality, is able to respond to the Word of God in a unique way.

There is something really beautiful about this. Because God creates us as individuals, each of us has an individual story and an individual life, and our response to God is going to be unique. And yet, when we come together as Church, we are united in the one truth of the Gospel, in the one Church of Christ and in the one Baptism.

What should we do when we do not understand the Bible?

- This is a really important concept for us. Each of us, in our particular vocation and life, needs to get to know God, read his word and allow ourselves to be changed and impacted by it. And we need to recognize that we will never know everything.

If we look back in the Christian tradition, we see many attempts in the lives of the saints and doctors of the Church, and even in ecclesiastical architecture, to make the Bible understandable. For example, if you walk through the famous Gothic cathedrals of France and look at the stained glass windows, they tell the stories of the Bible.

That is why I believe that in the life of the Church we have a constant need to grow in our relationship with God, in prayer and in knowledge. And this is where every effort we make to educate people about the Bible is really useful and valuable. Without that kind of education that accompanies Scripture, Scripture will remain a kind of dead letter or something that people cannot understand. That's why homilies should focus on teaching Scripture and its meaning. We need to publish books and commentaries that explain it and organize retreats, conferences and seminars. These are all great ways for people to understand more.

Now, it is true that there are certain topics in the Bible that are very difficult and require a lot of study to understand, but most of the topics in the Bible can be understood by children. As we learn and grow, more and more passages become clear to us. But there may be some that require additional study to really understand, and this is where I think scholars can be really helpful and solve the most difficult problems.

What would you say to someone who is lost trying to read the Bible?

- If they are reading on your own, I would start with the Gospel of John. But the real answer is to find a community. Find a parish, a Bible study group, a teacher or a school... A group of people who know the Bible and are able to teach about it in a way you can understand.

There are many videos and programs on YouTube, but the best thing is to find people. In the United States we have a lot of resources in this regard. The resources will become apparent as you do so. But the main thing, in my opinion, is to find a community of people who love the Bible and want to share it with you.