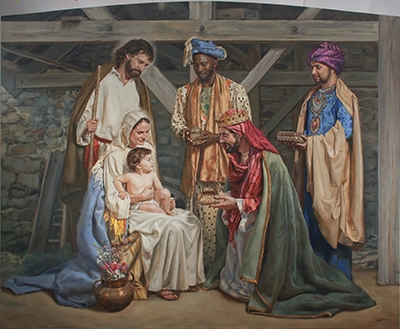

The Christmas season is undoubtedly one of the moments when sacred art shines with special strength. Christmas cards, representations of the nativity, the figures of the nativity scenes... art becomes, more than ever, a path of prayer and contemplation.

Together with her sisters, Maysa and Inma, Ignacio Valdeshas spent years dedicated to capturing images of religious content on canvas. Along with works of costumbrista style, this artist, born in Cadiz and trained at the Faculty of Fine Arts Santa Isabel de Hungría in Seville and at the Winchester School of Fine Art in Winchester, has taken scenes of the Holy Family, of present and past saints to hundreds of countries. In addition to Spain, he has works in England, Poland, Ireland, Japan, the United States, Russia, Croatia, South Africa, Mexico, Chile, Nigeria, Lebanon, Guatemala and Italy.

His paintings, realistic, close and colorful, center altarpieces and chapels, placing God, somehow, in the middle of the usual environment of the viewer. A materialization of the Way of Beauty that he carries out in a natural way, as he points out in this interview with Omnes: "While I am painting, I think of the people who, when they find themselves in front of that painting, it will help them to love God, or his Mother, more.

Says Antonio Lopez Do you believe that true religious art is the one that moves the viewer because it forgets the "artistic" to focus on the religious dimension? Is faith a premise for a religious work to really achieve its objective?

- It has always been difficult for me to find an answer to the fact that a sacred painting, technically well done, even catalogued as a work of art, does not arouse devotion in the spectator, does not reach the heart of the beholder, even though it is very pleasing to the eye.

And, paradoxically, the opposite is sometimes the case: how many images do we know that are not a "capo lavoro" but to which thousands of people pray!

I found the answer to this doubt in the book of St. Faustina Kowalska:

"Once, when I was in [the workshop] of that painter who painted that image, I saw. that it was not as beautiful as Jesus is. I was very distressed about that, however, I hid it deep in my heart. When we left the painter's workshop, Mother Superior stayed in town to settle various matters, I returned home alone. I immediately went to the chapel and wept so much. Who will paint you as beautiful as you are? In reply I heard these words: "The greatness of this image is not in the beauty of the color, nor in the beauty of the brush, but in My grace".

Certainly a work of sacred art must have a technical quality, so as not to fall into the ridiculous or the ugly, but on the other hand, in sacred art, the distance between what is represented and the way it is represented is infinite: not even the brushes of Velázquez or Rembrandt are able to come close to the beauty of God Himself. In this episode, St. Faustina speaks to us of an increase that God gives in the contemplation of the work of art, which goes beyond the beauty of the color: it is about the grace that he gives through the contemplation of the sacred image.

How can a painter make his works be instruments of God's grace? Is it a matter of forgetting "the artistic to focus on the religious dimension, as Antonio López says, or painting from faith?

- This belongs to the mystery of God, although I sense that it may be related to the "intention" of the artist when painting. If the underlying intention of the artist when he is painting a specific sacred painting is: love for what you represent, the service you render to God, to the Church, to others; reparation for your sins..., it is easier for God to use it as an instrument to grant his grace to those who contemplate the work. And for this, faith is undoubtedly necessary.

However, if the underlying intention of the artist is: to be praised by others, to be above our competitors, to profit economically... Although artists need praise, a healthy competition makes us improve, and earning money with something that not many know how to do is more than fair, all this is reasonable, but if they occupy the first place in the intentions, it would turn the work into a defective instrument of God's grace, even if that person has faith.

Even so, God can, and so often does, use those imperfect works and "turn stones into children of Abraham", hence my difficulty in answering that question.

Is it possible to praying before one's own workHow is the dialogue between a painter with faith and a religious work that aims at such an intimate sphere?

- It is very difficult for me to pray in front of a picture I have painted, because I immediately see it in brushstrokes, I can't help it. Sometimes when you are painting, I think of the people who, when they find themselves in front of that picture, it will help them to love God more, or their Mother.

We artists hardly know anything about those intimate stories; and that's a good thing because you might think that all the success is yours, and it's not true.

Sometimes I find myself with a special difficulty in the process or I don't know where to start: I have an infallible trick that consists of asking for help to the one I am representing in the painting. The last straw is when you "cross" that request, for example: I am trying to paint the Baby Jesus, and I say to his Mother: "You want me to paint your handsome son, don't you?" It doesn't fail.

When you approach the painting of the Virgin Mary, of St. Joseph, are you aware that there will be people who will materialize their prayer through these images, that they are "putting a face" to God? Is it a responsibility or a challenge?

- The subject of the mental image we have of God the Father, of Jesus, of the Virgin..., is very interesting. We think with images and we need them. Since the second Person of the Blessed Trinity, Jesus Christ, was incarnated in Mary's womb, he already has a concrete body, a unique, singular face, recognizable by those around him.

In the Old Testament, God had forbidden his representation in an image, to avoid the contagion of the neighboring peoples and to avoid falling into idolatry; we already know how the golden calf ended... But, from the Incarnation on, everything changes, and God himself is presented with the face of Jesus. Mary and Joseph also have specific, unique features. Christian art has been creating images of them with the imagination of artists and the devotion of the people.

The image of Jesus Christ was fixed from very early on, thanks to the "mandylion" and the Holy Shroud, but the faces of the Virgin, St. Joseph, the apostles, etc, have been represented in various ways, although there has never been a common thread in the history of art that helps us to recognize the characters represented: elements of costumes, poses, attributes... But each era and each artist has his own way of representing them.

In the end, as it happens in every family, everyone has their own preferences, and I am not only talking about tastes, but also about the devotion they feel or the mystery they perceive: if one prefers a Renaissance Virgin to address Her, then great.

I try to represent the Virgin and St. Joseph as I imagine them, without trying to break the thread I was talking about before, but I know that when you make a new image, at first it can be shocking, because we already had another consolidated mental image, but the passage of time fixes it.

It happened to me, for example, with the actress who played the Virgin in the film "The Passion", at first I was shocked, and now I am no longer. I am an advocate of the idea that sacred art is a service to others, in that sense it is a challenge.

What is the face of the Madonna for you, whom you have portrayed with assiduity?

- Our Lady is first and foremost my Mother. She has the face of a mother and there is no need for me to explain how mothers are because we all know it. Something a little mysterious also happens to me and that is that in every woman's face, I perceive a glimpse of Mary, even if that woman has her flaws, so when a model poses me, I try to reflect that glimpse.

In recent years, we have seen a religious art that could be described as "close": family or intimate scenes of the Holy Family, an incorporation of the new saints, and a new way of seeing the world.. Does painting also adapt to the new language of believers, of society?

- I don't believe that painting has to adapt to the new language of society, artists are part of that same society, so if we try to be ourselves, we express ourselves with the same language. On occasions, someone has commented to me that my images are too "real" and that they need to be "idealized" a little more. I understand that in sacred painting one cannot be banal and that it is necessary to reflect the mystery of the supernatural, but it happens that when so much emphasis is placed on "the ideal", the images move away from us to an interstellar space: they represent characters who are not with us and we have to go to them. This is the current drama of the Christian: who acts throughout the day thinking that God, the Virgin, the angels, the Saints, are far away from us, on another plane... very far away, and that they don't care much about us: it turns out that the opposite is true. I think it is important to remember this idea of "closeness" also through painting.

Is religious painting experiencing a new golden age or, on the contrary, is it going through a complicated moment?

- I lack the time perspective to be able to give a clear answer. To situate ourselves, in the sixties and seventies of the previous century, an iconoclastic movement began within the Church, the reasons are not relevant, but the fact is that, somehow, we still suffer from that inertia. In those years, in the artistic panorama, the only acceptable thing was the abstract language and the consequent marginalization of any figurative language. This influenced the artistic elements inside the churches, creating the paradox of a "sacred abstract imagery", two terms: image and abstraction, which are contradictory.

The problem is that the absence of images is not a Christian option, as Benedict XVI affirmed. In that context, Kiko Argüello proposed a neo-icon language for images, and somehow, the only figurative paintings we saw in those years in modern churches were precisely of this style: at least they were figurative.

I chose a realistic style for sacred painting, first because I liked it more, and then because I saw it closer to the devotion of the people. As time went by I began to teach at the Sacred Art School in Florence, and from there we are forming promotions of new artists for the whole world, they are students from all countries and they learn first the technique of painting and in a second step, to make sacred painting, which is the most difficult.

I believe that little by little this new proposal is being accepted, because the quality of the painter's craft is getting better and better and the training in Sacred Scripture, Art History, Liturgy, Christian Symbology and Theology, completes a background in the student that makes that when he paints a picture, it is not only a technically well done picture, but one that tries to convey the mystery of our faith.