"You shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem throughout Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth" (ἔσεσθέ μου μάρτυρες ἔν τε Ἰερουσαλὴμ καὶ ἐν πάσῃ τῇ Ἰουδαίᾳ καὶ Σαμαρείᾳ ἕως ἐσχάτου τῆς γῆς) (Acts of the Apostles 1:8).

One cannot speak of Christianity in Japan-as elsewhere in the world-without using the word "martyrdom," a term derived from the Greek μάρτυς, meaning "testimony."

The martyrs

In the Letter to Diognetus, a short apologetic treatise addressed to a certain Diognetus and probably composed at the end of the second century, Christians are told of a place assigned to them by God, a place from which they cannot leave.

The term used to define this place, this "place," τάξις (táxis), indicates the disposition that a soldier must maintain during a battle. Consequently, the Christian is not only a witness in the juridical sense, as one who testifies in a trial, but he is Christ himself, he is a seed that must die and bear fruit.

And this points out the need, for those who know a Christian, not only to hear him speak of Jesus as of any historical figure who has distinguished himself by saying or doing something important, but to see, taste, feel Jesus in person, present before his eyes, Jesus who continues to die and rise again, a person of flesh and blood, with a body that can be touched.

Types of martyrdom

The witness, the "martyrdom" to which every believer in Christ is called, is not necessarily - as many might think - the violent death suffered by some, but the life of a martyr, which inevitably leads to the κένωσις (kenosis), a Greek word that literally means "emptying" and, from the Christian point of view, the renunciation of oneself in order to conform oneself to the will of God who is Father, as Jesus Christ did throughout his life, and not only in the act of dying on the cross.

If we apply this definition to the concept of holiness, we could say that many saints (and by saints we do not mean only those canonized by the Church, but all those sanctified by God) are martyrs even though they did not sacrifice their corporal life. They are saints, however, because they have given witness to holiness with their lives.

In Catholicism, in fact, three types of martyrdom are considered:

- the white, which consists in the abandonment of all that man loves for the sake of God and faith;

- green, which consists of freeing oneself from evil desires through penance, mortification and conversion;

- the red, that is, to suffer the cross or death for the faith, also considered, in the past, as a purifying baptism of all sin that assured sanctity.

Japanese martyrs

And indeed, throughout history, Japan has recorded thousands of martyrs in all the categories we have listed. One "white" martyr, for example, is the blessed samurai Justus Takayama Ukon (1552-1615), beatified in 2017 by Pope Francis and also known as the Japanese Thomas More.

Indeed, like the Chancellor of England, Takayama Ukon was one of the major political and cultural figures of his time in his country. After being imprisoned and deprived of his castle and lands, he was sent into exile for refusing to abjure the Christian faith he professed.

His persecutor was the fierce Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who, despite numerous attempts, was unable to subdue Ukon, who, in addition to being a Christian, was a daimyo, that is, a Japanese feudal baron, as well as an outstanding military tactician, calligrapher and master of the tea ceremony.

Christian mission in Japan

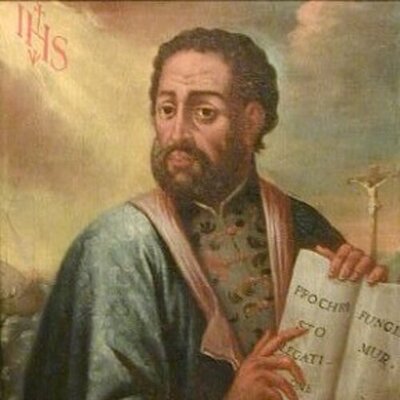

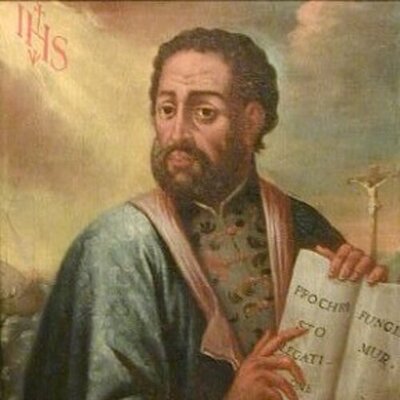

The Christian mission in Japan began on August 15, 1549, the day on which the Spaniard St. Francis Xavier, founder of the Jesuit Order together with St. Ignatius of Loyola, landed on the island of Kyushu, the southernmost of the four large islands that make up the Japanese archipelago.

The Jesuits preceded the Franciscan friars by a small margin. Foreigners arriving in southern Japan in their dark-colored boats (kuro hune, or black boats, in Japanese, to distinguish them from local boats made of bamboo, usually lighter in color) were called nan banji (southern barbarians). In fact, they were considered rather coarse and uncouth people, for different reasons.

The first was the fact that they did not follow the customs of the country, all of which were based on the codes of chivalry forged by the practice of bushido. This practice, based on ancient Japanese traditions and Shintoism (Japan's original polytheistic and animistic religion, in which kami, i.e. divinities, natural spirits or simply spiritual presences such as ancestors, are venerated), had at its core the rigid division of Japanese society into castes.

The highest ideals were embodied by the bushi, the noble knight, who shaped his life around the virtues of valor, faithful service to his daimyo (feudal baron), honor to be preserved at all costs, the sacrifice of life in battle or by seppuku or harakiri, ritual suicide.

Development of Christianity in Japan

During the 16th century, the Catholic community grew to over 300,000 people. The coastal city of Nagasaki was its main center.

The great promoter of this flowering of new believers was the Jesuit Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606). He arrived in Japan in 1579 and was appointed superior of the Jesuit mission in the islands. Valignano was a well-prepared priest (all Jesuits were at that time), strong in his studies as a lawyer.

Before being appointed superior, he had been master of novices and had been in charge of the formation of another Italian, Matteo Ricci, who would later become famous as a missionary in China.

Alessandro Valignano's main intuition was to realize the need for Jesuits to learn and respect the language and culture of the peoples they evangelized, disassociating the proclamation of the Gospel from belonging to one culture and not another: the faith, according to his vision, was to be transmitted through inculturation, that is, to become an integral part of the local culture.

He also wanted the natives, the Japanese, to become promoters and managers of the mission in their country, in a kind of handover that at the time was considered somewhat shocking.

Valignano was also responsible for the first fundamental manual for missionaries in Japan, as well as a work on the customs of the Land of the Rising Sun, including the famous tea ceremony, to which he asked that a room be dedicated in every Jesuit residence, given the great importance of this ritual in the East.

Thanks to the missionary policy of inculturation practiced by Valignano, several Japanese notables and intellectuals, among them a good number of daimyo, converted to the Christian faith or at least showed great respect for the new religion.

Reticence about missions

Within the ruling regime, the Tokugawa shogunate (the shogunate was a form of military oligarchy in which the emperor had only nominal power, since in reality it was the shogun who exercised the political leadership of the country, assisted by local squires), and in particular the crown marshal in Nagasaki, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, viewed the work of the Jesuits with increasing suspicion.

It was feared that, through their evangelizing mission, foreign missionaries, reinforced also by the growing number of converts, might pose a threat to the stability of their power, given their privileged relations with foreign countries. And, come to think of it, this was entirely plausible: in fact, Japan had a system of power and a culture that did not consider the life of every person as something of value at all.

The system itself was based on the domination of a few nobles over the mass of citizens, who were considered animals (the bushi, the noble knight, was even allowed to practice tameshigiri, that is, to try out a new sword by killing any villager).

Everything could and should be sacrificed for the good of the state and the "race". Therefore, there could be nothing more threatening to this type of culture than the message of those who preached that all human life is worthy and that we are all children of the same God.

Writer, historian and expert on Middle Eastern history, politics and culture.