The last congress on the fundamental theology of the priesthood (February 17-19, 2022 in Rome), convoked by Cardinal Marc Ouellet, Prefect of the Congregation of Bishops, challenged all the particular churches. Above all, it highlighted certain fundamental points about the crisis of the priesthood that had been neglected or even ignored until then. In fact, for a good number of observers, and even Christians, who do not always distinguish between causes and consequences, the crisis of the priesthood, the crisis of faith, is manifested primarily by the phenomenon of the crisis of vocations. The depletion of vocations, the emptying or even the closing of seminaries, novitiates and other houses of formation, the disappearance of entire religious communities, have preoccupied the Western churches for several decades, and they continue to seek appropriate solutions.

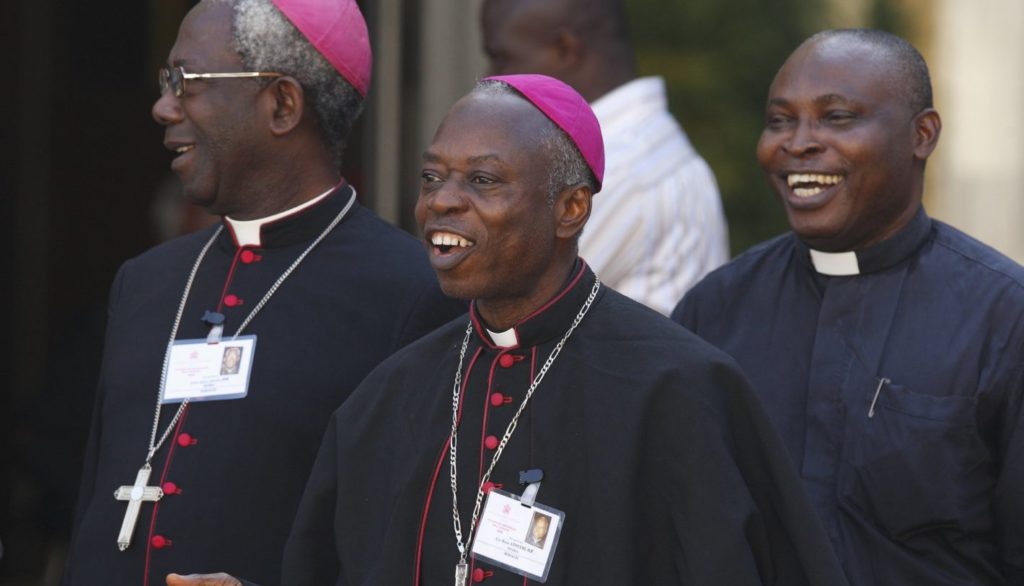

Contrast in the Church in Africa

This contrasts with the Church in Africa, which is growing in number to the point of arousing the interest of the great Western European secularist or secularist newspapers (Le Monde, Le Figaro, etc.). The number of priests is increasing with impressive and very enviable figures. In some parts of the continent, the number of priests has increased by 85% in twenty years, that of nuns by 60% and that of bishops by 45%. The recent publications of the statistical yearbooks of the Holy See highlight this real vocational boom in the African Church. A crisis of the priesthood in Africa appears then as an absurd and incoherent thesis, a nonsense and therefore difficult to defend.

The congress on the priesthood held last February made it possible to see beyond the mere numerical and statistical manifestation of the crisis that the priesthood is going through and that only affects some churches. The systemic and empirical crisis is much deeper and more damaging. In this sense, African communities are facing a crisis of substance, form and substance. The fundamental crisis occurs when the doctrinal basis of the priesthood is not correct and, consequently, affects the very identity of the priest, his human and spiritual life and his priestly action.

The crisis of form is certain when the multiple faces assumed by the priesthood are out of step with the expectations of the people and the objectives of the mission, and when they deviate from what is essential to build on marginal issues or those alien to their purpose. The crisis is substantial because the priesthood is becoming conventional, that is, according to the convenience of a world whose desires are blindly followed.

The congress allows us, once again, to examine Africa, a continent that is not experiencing a decline in vocations because the vocation crisis is not a major concern compared to vocations in crisis. If several African pastors recognize that all vocations are a gift of God, they have questioned several times the authenticity of vocations. In fact, in an African society that is changing, that has evolved a lot, and that asks a lot of young people, especially those who desire an ideal of life, the risk for some that the priesthood is a way to advance in social status is more evident.

Coveted continent

Africa is today the market coveted by the epigones of the spiritual and evangelical barons who claim to fight against poverty in favor of prosperity. There is talk of a terra nulliusdivided into zones of influence, businesses and corporations. Poverty and the harshness of life, the father of all other challenges, the depravation of morals, the endemic unemployment of young people, even if they are graduates, who are now willing to do anything to make a living, even if it means throwing themselves into the Mediterranean, have been in the news for decades. This situation obviously has repercussions on the action of the Church. It influences the model of the priest and even dictates the profile of the priest to be formed. The precarious, deleterious and approximate social condition has indeed had repercussions on the ministerial priesthood.

The situation of the African clergy depends on the diverse context in which the ministry is exercised, the social and cultural dispositions and the varied investments of the priests. Ignace Ndongala Maduku describes the conditions of some African priests today as vagabonds in whom old age rhymes with distress, sickness with misery. We meet many functionaries of God, a state clergy and not pastors of the people. A constant concern of the African clergy is the material subsistence of the priests, which leads to the tacit establishment of privileges.

The language is often unusual and chilling in describing this aspect of the quality of life of African priests: ecclesiastical Darwinism. Moreover, their attitude to the elite and authority is castigated: bowing to superiors and stepping on inferiors, being humble before the authorities and authoritarian before the humble. In this context, appointments are perceived as advances, promotions that sometimes seem like plebiscites, sources of material advantages and various real or imaginary privileges. The lack of equality among priests and the deficit of social, material and financial security create a scandalous inequality and injustice among priests.

Training priority

There is, therefore, a real educational challenge in relation to the formation of future priests. The topic emerges more sharply in the face of current scandals, but in reality it must be brought to the attention of the entire Christian community, avoiding the logic of the scapegoat or that of the emergency. There is a very real risk that the priesthood is an escape route to achieve a social status that young people would not have in ordinary life. Some questions are essential today: Is the model of formation of future priests, inherited from the missionary era, still effective with regard to the profile of priests to be formed? Which priests? For which society? Does the framework of small and large reclusive seminaries that still exist today represent a stable guarantee for the maturation of priestly vocations?

The formation of true pastors is a priority for the African Church, it is the priority of priorities. It is a work that requires important men and means. The quality of formation and discernment is a permanent challenge with the necessary exigency. Moreover, the seminary is not the only "branch" responsible for the formation of candidates to the priesthood. The work of the seminary cannot be that of offering "finished products". A systemic vision is needed that involves pastors, formators, but also priests and the entire Christian community. Formation in the seminary involves, in an ascending sense, youth ministry and should favor a serious verification of the conditions of possibility for the development of specific persons in all areas of formation.

The vocational discernment of young people should closely follow the evolution of pastoral needs, ordering concrete actions in a precise direction. Much attention must be paid to good and holy discernment. It is true that not all seminarians become priests, but the speed of choice and the lack of discernment can lead young people today not to live their vocational discernment in depth, since society offers facilities and shortcuts.

"Examples lead."

An important and critical point, too often neglected in improving the quality of formation of future priests, remains the quality and concrete witness of priests, of bishops as a whole. Seminarians are often more sensitive than one might think to the general climate of clerical life. As an Italian saying goes: words teach, but examples guide. Since the horizon of formation is prospective and "future priests receive a formation in keeping with the importance and meaning to be given to their consecration", there are important reconstitutions of the role of the priest in African society according to the tria munera (to teach, to sanctify and to govern) which call for a redefinition and updating of the pastoral office.

Missionary animation and awakening, the biblical instance of the prophet, the memory of the universal call to holiness: baptism and not "sacramentalization" to the extreme seem to be the basis of a fruitful deepening and examination for an authentic priesthood also for the African Church.

Director of Studies at the Major Seminary of Theology of Yaoundé-Nkolbisson (Cameroon). Professor of Social and Political Ethics.