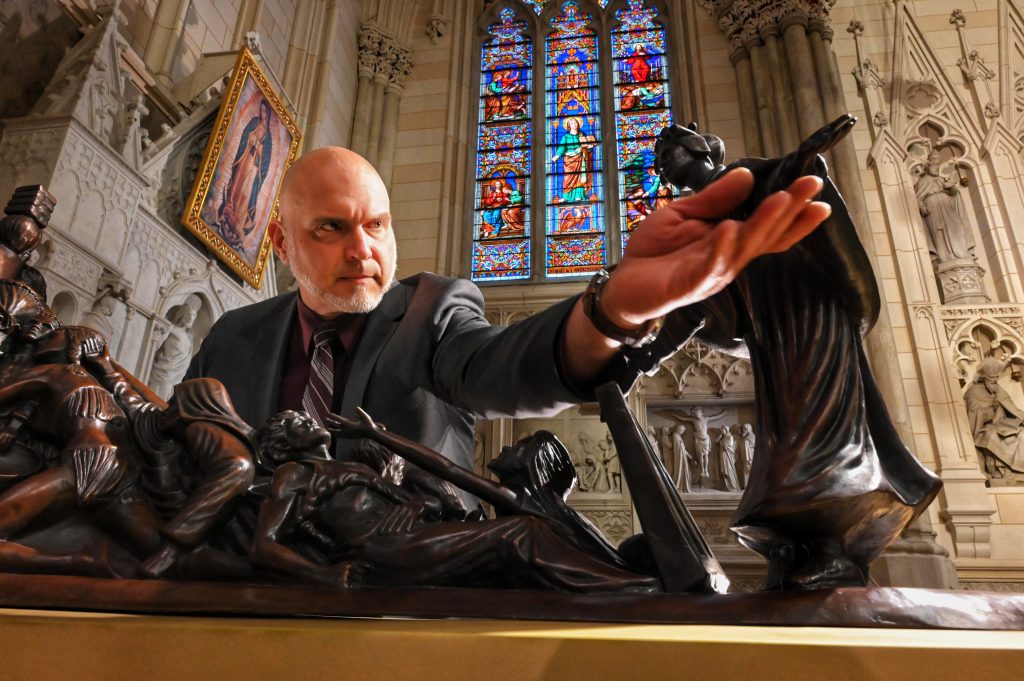

The drama of human trafficking is not new; unfortunately, it is all too familiar and pervasive in the United States. Even some of our Catholic saints were victims of this evil: St. Bakhita and St. Patrick, for example. But both triumphed and were strategically used as instruments to show God's miraculous glory. The statue of St. Bakhita, the patron saint of human trafficking, is on display in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican and was recently unveiled at the St. Patrick's Cathedral of New York during a mass. The statue "Let the Oppressed Go Free" was created by Timothy Paul Schmalz, a Canadian-born sculptor whose vocation is to bring the mystical body of Christ to the world through his sculptures.

Can epic works of art inspire and invite humanity in a way that books cannot? The Pope Benedict XVI believed that the "only really effective apologia for Christianity boils down to two arguments, namely, the saints the Church has produced and the art that has grown in its bosom." Moreover, he believed that "the encounter with the beautiful can become the wound of the arrow that strikes the heart."

Perhaps there is a correlation between Pope Benedict's sentiments and Timothy Schmalz's apostolic mission. The sculptor describes his works as "visual translations of the Bible," and his interest in the theology of the saints continues to inspire him.

Timothy Schmalz

Timothy Paul Schmalz was baptized Catholic but was born into a relatively "secular" home. In his early teens, he considered himself agnostic; however, at the age of seventeen, he had a "conversion experience," which was transformative and led him to identify as Catholic.

His father was head of an English department, and he recalls that he was "fed" a lot of great literature and was very "drawn" to philosophy, but at sixteen he knew he wanted to be a sculptor and realized it was his vocation. "Sculpture, sculpture, I was obsessed with artwork," Tim recalls. And when he was nineteen he was accepted to the Ontario College of Art. But he would later drop out because he had "an artistic crisis." He thought "it was bullshit" and didn't appreciate "the game that was being played where innovation and impact is everything."

Artistic conversion

At that point, Tim realized that if he was going to devote the rest of his life to doing works of art and sculpture, "they had better not be superfluous things and only ornamentation".

Timothy Schmalz invented his own school, inspired and directed by his predecessors, Michelangelo, Bernini and Davinci. He tells us how he felt "absolute joy and excitement" when he "picked up some clay" and created a simple representation of Christ. Realizing that it was an "artistic conversion" that he experienced, Timothy focused entirely on Christian works of art.

When Tim began his journey with religious sculpture, he knew that his discipleship was not simply about sculpting art, but about evangelizing. This world was foreign to him because he had been raised in a secular home. "I never had that experience of Mary with the little lamb," Timothy says.

In addition, he began to study the saints he represented and theology. He recalls that "it was an absolute zeal...and I embraced it!". He realized that his new passion was much more "awesome" than Greek philosophy.

Christian Art

Timothy's relationship with Father Larrabee, a Jesuit priest who would become his spiritual director and mentor, was a source of great support and guidance. He also loved Christian artwork, which inspired him. And at the age of 20, he learned not only about sculpture, but also about his Catholic faith "in a profound way, and with the help of great books."

He realized that there were endless possibilities with Christian artwork and "the amount of expression that could be put into it." He was interested in more than just the shock value of the art or whether it was innovative. He was "rebelling against the secular pop culture" that was around at the time. Timothy recalls, "He was doing the most radical thing at the time: Christian artwork."

The enthusiasm and curiosity he felt towards Christianity excited him.

Revealing the message

At first, he made life-size pieces and, over time, more sculptures, mostly for churches. He recounts how "complex" his sculptures became as they increased in size. "I wasn't interested in just doing something; if I was going to do a sculpture of St. Francis, I wanted to study St. Francis," Timothy recalls.

He remains committed to getting to know the souls and apostolic mission of the people he sculpts. He considers his work a "visual opportunity". For Timothy, visual works of art are an effective way to reach people because they only require a quick glance at the piece. He believes that if a sculpture is done authentically, the message of the saint or the gospel will reveal itself.

Timothy not only works with consummate skill, but also believes it is his responsibility with "his hard work, muscle and heart...to move and convert people." He continues, "And if they don't, it's my fault; it's my problem, not Catholicism, not our faith, not the artwork."

Theocentric art

When he sketches a sculpture, he is not interested in the style; he believes that "the work of art should be secondary". The essential thing is to reveal Jesus or the saint in the artwork. And if that happens, then "I'm doing a great job," Timothy says. "Art, for art's sake, is a snake that eats its own tail." His quest as an artist has little to do with style or material; instead, it has to do with trying to discover "the Scripture or the essence of the saint."

Sculpture is nothing more than an instrument to help convert people. Besides, what is important is the subject matter and what is depicted. Tim listens to the Bible for eight hours a day to create a space in his studio that is "more like a chapel...or where work and prayer merge."

Interpretation of Hebrews 13:2

Tim speaks of a "eureka moment" when he heard the passage from Hebrews 13:2 some years ago. "Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for in doing so, some people have shown hospitality to angels without knowing it." He said it was the "most poetic passage in Scripture" and that it inspired him so deeply that it led him to begin creation on Hebrews 13:2.

A year later, while in Rome, Cardinal Czerny asked Timothy to make a sculpture about immigrants and refugees. The idea of how to depict the verse would occur to him shortly after his arrival home.

In Timothy's words, "I came up with the idea: A huge raft or a boat with a crowd of people from all over the world, all immigrants and refugees, all on a little raft, shoulder to shoulder, from all over the world, from all periods of history, and in the center of this raft is an angel; but because of the crowd, you can only see the wings, and so the wings become the wings of all the people on this boat. And that's my interpretation, my carving of Hebrews 13:2. If I hadn't been immersed in the Scriptures that day...maybe I wouldn't have done anything."