Mercedes Temboury Redondo, PhD in Modern Spanish History and tireless researcher of the Spanish Supreme Inquisition and its suffragan courts in the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, in the funds of the National Historical Archive of Spain, presents in this extensive volume which we now comment on a synthesis of his research.

The Unknown Inquisition: The Spanish Empire and the Holy Office

The angle of vision of this work and its objective coincide in offering a synthesis of the Inquisition from the perspective and interests of the Spanish Empire in Europe, Asia and America during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The black legend

This vision attempts to illuminate the dark points of the black legend fabricated especially by Juan Antonio Llorente, the last Secretary of the Supreme Inquisition who went into exile in France in the 19th century and lived off the publication of the "secret" papers he had taken from the archives.

In fact, it has been many years since the Pope St. John Paul II provided the necessary light to understand the origin and theological errors of the Spanish Inquisition. On March 12, 2000, in an impressive ceremony at the Vatican in front of a 12th century crucifix, the Holy Father, surrounded by his cardinals of the Curia, asked forgiveness for all the sins of all Christians of all times and, especially, for the use of violence to defend the faith.

Indeed, Roman law affirmed, and as such passed on to the Church the principle: "de internis neque Ecclesia iudicat". Of internal things neither the Church can judge, only God knows the interior of man.

Theological error of the Inquisition

The theological error of the Inquisition consisted, therefore, in trying to force the conversion of the accused by means of a juridical process. As is the common doctrine of the Church, and as the New Testament and Tradition state, only the grace of God can open the soul to conversion: "No one comes to me unless the Father draws him" (Jn 6:40). Therefore, only persuasion and prayer and penance and good example can stir souls to repentance and rectification.

As all those who have exercised spiritual direction or spiritual accompaniment know well, when a person is sincere in the Sacrament of Penance, with that gift comes the gift of contrition and the soul can regain the peace of God's mercy. To catch a person in the lack of coherence of faith and life and attempt repentance only leads to hardening of the heart and wounded pride.

Indeed, the studies that we have carried out on the subject and that we have published in many articles and monographs on the "theological error of the Inquisition", shed this light: the objective of the inquisitorial process was to objectify the theological error in which the defendant had fallen and then seek conversion under pressure: the Judaizing heresy, the apostasy and return to Islam of the new convert, the denial of the sins established by the positive divine law. The inquisitors usually had a good heart and knew that they had to give an account to the Supreme Court of their rectitude of intention and to God who is the Lord of consciences, that is why so many files are preserved and so prolix.

Spiritual and legal finesse

Evidently, this was a mistake for which we must ask forgiveness because, even if only a single process had taken place, we should already repent and rectify. It is necessary to return to trust in God who will move the soul to conversion and in man who can repent and rectify before the good example and happiness of other Catholics: "If your brother sins against you, go and correct him alone with him. If he listens to you, you have won your brother. If he does not listen, then take with you one or two, so that any matter may be made firm by the word of two or three witnesses But if he will not listen to them, tell it to the Church. If he will not listen to the Church either, consider him a pagan and a tax collector" (Mt 18:15-17).

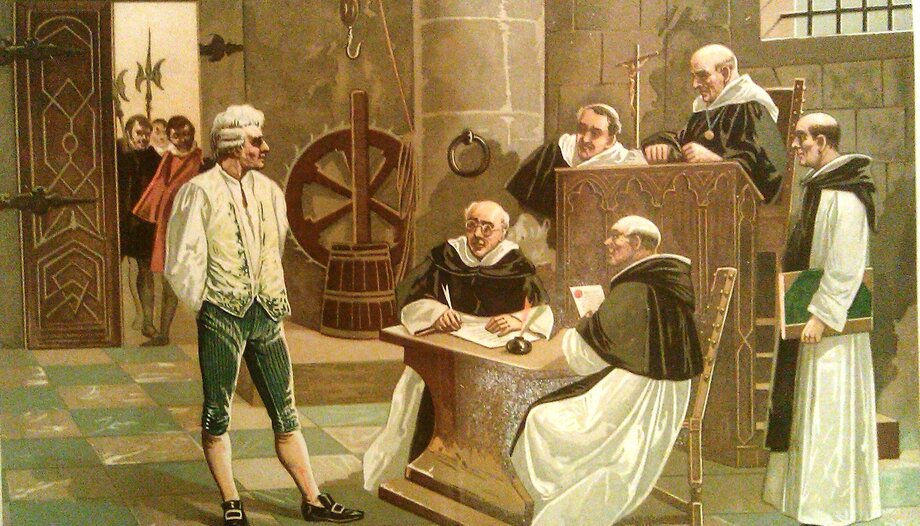

On the other hand, our author's analysis is full of juridical finesse, thanks to which she demonstrates that the procedural system of the Inquisition protected the defendants from the temptation to seize the assets of the accused or to be condemned for false accusations or to resolve problems of enmity or litigation in the villages. In fact, as the author demonstrates, the complex legal system yielded impressive results: most of the trials ended in the acquittal of the accused because they were not really heretics but people with a lack of elementary Christian education. A few were indeed condemned for heresy, but, upon repentance, they were given medicinal sentences. And only a very few were condemned to death. As Jaime Contreras has already shown in his Inquisition database, only 1.8 % were handed over to the secular arm.

Evidently, only an inquisitorial process would be enough to ask forgiveness for having violated conscience, even if it is argued, as the author does, that the inquisitorial process saved us from events such as: the 50,000 Huguenots murdered in France on the night of Saint Bartholomew, August 23-24, 1572; the 500,000 witches burned in Germany in the Lutheran trials without papers; the death of Michael Servetus by Calvin simply to compensate for the offended divine justice and the martyrdom of the Jesuit Edmund Edmund Servetus.000 witches burned in Germany in the Lutheran trials without papers; the death of Michael Servetus by Calvin simply to compensate the offended divine justice and the martyrdom of the Jesuit Edmund Campion and many other Catholic priests in England because the Anglican inquisitorial court considered them guilty of death for celebrating the Catholic Mass as that would be high treason to Queen Elizabeth, head of the Anglican Church.

A new vision

In reality, this work is a new vision of the Inquisition taken from the reading and research of many files taken from the National Historical Archive and other archives consulted. The author has focused especially on the second life of the inquisitorial process. That is, from 1511 to 1833. In this period, the Inquisition should have disappeared since it had been created for the processes against judaizers and these practically disappeared during this time.

Indeed, it is understood that the aim of this book is to demonstrate that the Inquisition worked above all at the service of the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of the Spanish Empire at a time of close union between civil and ecclesiastical power when the unity of the faith was capital for the renewal of the Church after Trent and the expansion of the Spanish empire in America and Asia.