St. Jerome was born in Stridon (Dalmatia) into a Christian family, and received a solid formation in Rome. He was converted and baptized around 366. He lived for a time in an ascetic community in Aquileia. His ascetic life is another legacy of the saint, as Pope Benedict XVI comments: "He has left us a rich and varied teaching on Christian asceticism. He reminds us that a courageous commitment to perfection requires constant vigilance, frequent mortifications, albeit with moderation and prudence, assiduous intellectual or manual work to avoid idleness, and above all obedience to God".

Later, St. Jerome left the community of Aquileia and was in different places: Trier, his native Stridon, Antioch or the desert of Chalcis (south of Aleppo). In addition to Latin, he knew Greek and Hebrew, and transcribed codices and patristic writings.

He was ordained a priest in 379 and left for Constantinople. There, he continued his Greek studies with St. Gregory Nazianzen. He also met St. Ambrose and corresponded with St. Augustine.

Counselor to the Pope

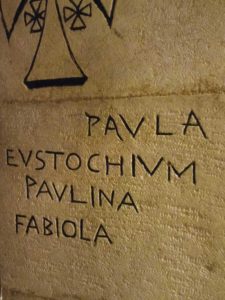

Later, in 382, he moved to Rome and became secretary and advisor to Pope St. Damasus. The latter asked him to make a new translation of the Bible into Latin. In addition, in Rome he was the spiritual guide of several members of the Roman aristocracy, mainly women, such as Paula, Marcela, Asela and Lea. With him, these noblewomen deepened their reading of the Bible in a "cenacle founded on the rigorous reading and study of Scripture", according to Pope Francis in a apostolic letter on St. Jerome published in 2020 for the XVI centenary of his death.

In 385, after the Pope died, St. Jerome left for the Holy Land, accompanied by some of his followers. After passing through Egypt, he went to Bethlehem, where, thanks to the aristocratic Paula, he formed two monasteries, one for men and one for women, and a place of lodging for those who were on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, "thinking that Mary and Joseph had not found a place to stay".

In Bethlehem

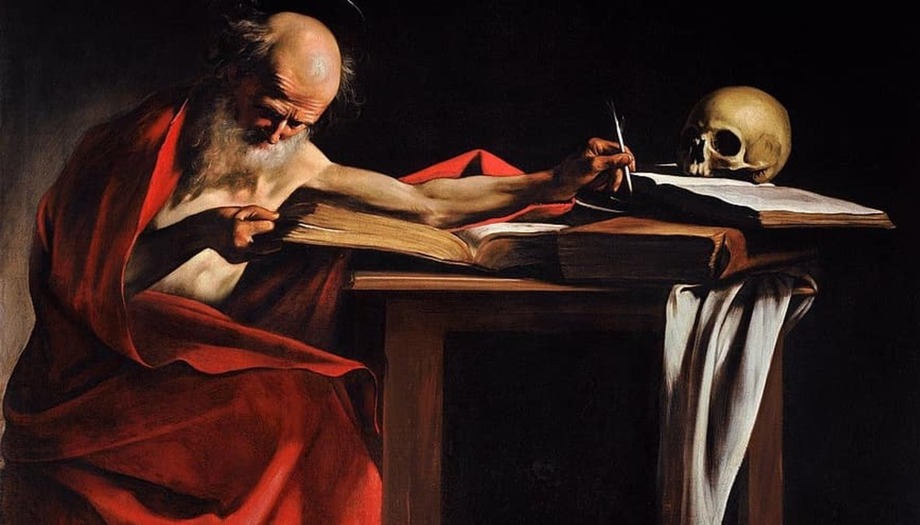

In the caves of Bethlehem, near the Grotto of the Nativity, he made the Vulgate, a Latin translation of the entire Bible. In addition, St. Jerome "commented on the word of God; he defended the faith, vigorously opposing various heresies; he exhorted monks to perfection; he taught classical and Christian culture to young students; he welcomed pilgrims visiting the Holy Land with a pastoral spirit," commented Pope Benedict XVI in two audiences in 2007 (7 y on November 14) dedicated to St. Jerome. In these same grottoes the saint died on September 30, 420. He was proclaimed doctor of the Church in 1567 by Pius V.

Pope Benedict XVI indicated that St. Jerome "put the Bible at the center of his life: he translated it into Latin, commented on it in his works, and above all strove to live it concretely in his long earthly existence, despite the well-known difficult and fiery character that nature gave him."

How his love for Scripture was born

Pope Francis indicates in the apostolic letter "Scripturae Sacrae Affectus" that, curiously, St. Jerome's love for Scripture was not born from the beginning. The Pope points out that St. Jerome "had loved from his youth the limpid beauty of the classical Latin texts and, in comparison, the writings of the Bible seemed to him, at first, coarse and imprecise, too rough for his refined literary taste." However, he had a dream in which the Lord appeared to him as a judge: "Questioned about my condition, I answered that I was a Christian. But the one who sat there said to me: 'You are lying; you are a Ciceronian, you are not a Christian'". It was as a result of this dream that St. Jerome realized that he loved the classical texts more than the Bible, and there began his love for the Word of God.

The Pope also comments: "In recent times, exegetes have discovered the narrative and poetic genius of the Bible, exalted precisely for its expressive quality. Jerome, instead, what he emphasized in the Scriptures was rather the humble character with which God revealed himself, expressing himself in the rough and almost primitive nature of the Hebrew language, compared to the refinement of Ciceronian Latin. Therefore, he did not devote himself to Sacred Scripture out of an aesthetic taste, but - as is well known - only because it led him to know Christ, because to ignore the Scriptures is to ignore Christ."

Bible translation process

The Pope also commented on the process that St. Jerome followed in translating the Bible: "It is interesting to note the criteria that the great biblical scholar followed in his work as a translator. He reveals them himself when he affirms that he respects even the order of the words of the sacred Scriptures, for in them, he says, 'even the order of the words is a mystery,' that is, a revelation.

Moreover, he reaffirms the need to have recourse to the original texts: 'If a discussion should arise among the Latins about the New Testament because of discordant readings of the manuscripts, we must have recourse to the original, that is, to the Greek text, in which the New Testament was written. The same thing happens with the Old Testament, if there is divergence between the Greek and Latin texts, we must have recourse to the original text, the Hebrew; in this way, everything that springs from the spring we can find in the streams'".

The Vulgate

The Vulgate was so called because it was quickly accepted by the "vulgar", the people. Pope Francis explains its origin in this way: "The 'sweetest fruit of the arduous sowing' of the study of Greek and Hebrew by Jerome is the translation of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew into Latin. Until that time, Christians in the Roman Empire could only read the Bible in Greek in its entirety. While the New Testament books had been written in Greek, for the Old Testament there was a complete translation, the so-called Septuagint (i.e. the version of the Seventy) made by the Jewish community of Alexandria around the 2nd century BC.

For Latin-speaking readers, however, there was no complete version of the Bible in their own language, but only some partial and incomplete translations from the Greek. Jerome, and after him his followers, had the merit of having undertaken a revision and a new translation of the whole of Scripture. With the encouragement of Pope Damasus, Jerome began in Rome the revision of the Gospels and the Psalms, and then, in his retreat in Bethlehem, he began the translation of all the Old Testament books, directly from the Hebrew; a work that lasted for years.

To complete this work of translation, Jerome made good use of his knowledge of Greek and Hebrew, as well as his solid Latin training, and utilized the philological tools at his disposal, in particular the Hexaplas of Origen. The final text combined continuity in the formulas, now in common use, with a greater adherence to the Hebrew style, without sacrificing the elegance of the Latin language. The result is a true monument that has marked the cultural history of the West, shaping theological language. Overcoming some initial rejections, Jerome's translation immediately became the common heritage of both scholars and Christian people, hence the name Vulgate. Medieval Europe learned to read, pray and reason from the pages of the Bible translated by Jerome".

Possibility of new translations

"The Council of Trent established the 'authentic' character of the Vulgate in the decree 'Insuper,'" the Pope continues, "however, it did not intend to minimize the importance of the original languages, as Jerome did not fail to recall, much less to prohibit new works of integral translation in the future. St. Paul VI, taking up the mandate of the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council, wanted the revision of the Vulgate translation to be completed and made available to the whole Church. Thus it was that St. John Paul II, in the Apostolic Constitution Scripturarum thesaurus, promulgated in 1979 the typical edition known as Neovulgata".

Reading in the light of the Church

At the hearing of the November 14, 2007Pope Benedict XVI continued his reflection on St. Jerome by stressing the importance of reading the Scriptures in the light of the Church, and not alone: "For St. Jerome, a fundamental methodological criterion in the interpretation of Scripture was harmony with the magisterium of the Church. We can never read Scripture on our own. We find too many closed doors and we easily fall into error. The Bible was written by the people of God and for the people of God, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

Only in this communion with the people of God can we really enter with the 'we' into the core of the truth that God himself wants to communicate to us. For him an authentic interpretation of the Bible had always to be in harmony with the faith of the Catholic Church (...) In particular, since Jesus Christ founded his Church on Peter, every Christian, he concluded, must be in communion 'with the Chair of St. Peter. I know that on this rock the Church is built'. Therefore, he openly declared: 'I am with whoever is united to the Chair of St. Peter'".

Pope Francis also indicates in this regard that for St. Jerome it was very important to consult the community: "The valuable work found in his works is the fruit of dialogue and collaboration, from the copying and analysis of the manuscripts to their reflection and discussion: to study 'the divine books I never relied on my own strength nor had as a teacher my own opinion, but I used to ask questions even about those things I thought I knew, how much more about those of which I was doubtful! That is why, aware of his own limitations, he continually asked for help in intercessory prayer, so that the translation of the sacred texts would be done 'in the same spirit in which the books were written'".

Study and charity

His love for Scripture did not cause him to neglect charity. Benedict XVI quotes some words of the saint in this regard: "The true temple of Christ is the soul of the faithful: adorn this shrine, embellish it, deposit your offerings in it and receive Christ. What is the point of decorating the walls with precious stones, if Christ dies of hunger in the person of a poor person?".

In the same way, St. Jerome said that it is necessary "to clothe Christ in the poor, to visit him in those who suffer, to feed him in the hungry, to welcome him in those who have no home".

Female education

The saint was also a great promoter of pilgrimages, especially to the Holy Land, and of women's education, as Benedict XVI points out: "An aspect rather neglected in ancient times, but which St. Jerome considers vital, is the promotion of women, to whom he recognizes the right to a complete formation: human, academic, religious and professional".

In this regard, Pope Francis comments in his apostolic letter that two of these disciples, Paula and Eustochius, he "entered into 'the discrepancies of the translators' and, something unheard of at that time", he allowed them "to read and sing the Psalms in the original language".

Translation as a work of charity

Pope Francis also comments that the work of translation is a form of inculturation, and therefore of charity: "Jerome's work of translation teaches us that the values and positive forms of every culture represent an enrichment for the whole Church. The different ways in which the Word of God is proclaimed, understood and lived with each new translation enrich Scripture itself, since - according to the well-known expression of Gregory the Great - it grows with the reader, receiving over the centuries new accents and new sonority.

The insertion of the Bible and the Gospel in different cultures makes the Church more and more manifest as 'sponsa ornata monilibus suis'. At the same time, it testifies that the Bible needs to be constantly translated into the linguistic and mental categories of every culture and every generation, even in the secularized global culture of our time".

In this regard, he adds: "It has been rightly recalled that it is possible to establish an analogy between translation, as an act of linguistic hospitality, and other forms of hospitality. Therefore, translation is not a work that concerns only language, but corresponds, in fact, to a broader ethical decision, which is related to the whole vision of life. Without translation, the different linguistic communities would not be able to communicate with each other; we would close the doors of history and deny the possibility of building a culture of encounter.

Indeed, without translation there is no hospitality and hostile actions are strengthened. The translator is a bridge builder. How many rash judgments, how many condemnations and conflicts arise from ignoring the language of others and not striving, with tenacious hope, in this infinite test of love that is translation! (...) Many are the missionaries to whom we owe the precious work of publishing grammars, dictionaries and other linguistic tools that provide the basis of human communication and are a vehicle of the 'missionary dream of reaching everyone'".

The Word of God transcends time

The legacy of St. Jerome can be summed up with this beautiful comment by Pope Benedict XVI in one of his audiences on the saint: "We must never forget that the word of God transcends time. Human opinions come and go. What is very modern today will be very old tomorrow. The word of God, on the contrary, is the word of eternal life, it carries in itself eternity, that which is valid forever. Therefore, by carrying in us the word of God, we carry eternal life".