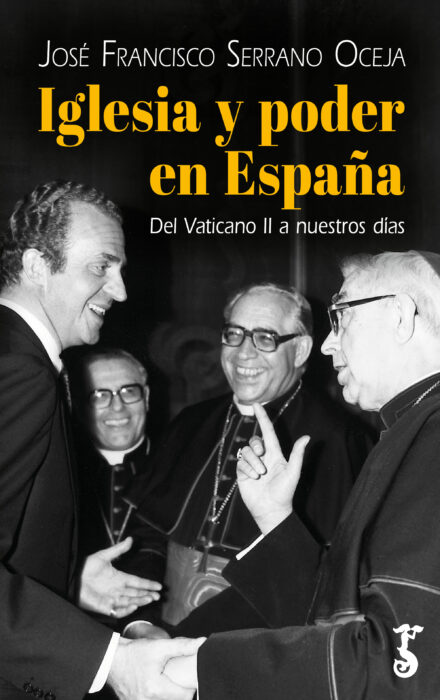

José Francisco Serrano Oceja. Church and power in Spain. From Vatican II to the present day. Arzalia ediciones, Madrid 2024, 375 pp.

José Francisco Serrano Oceja (Santander, 1968), professor of journalism at the Universidad San Pablo-CEU in Madrid and professor of contemporary history, has just published an interesting essay on the relationship between the Church and civil society from the Second Vatican Council to the present day. Let's take a brief look at it.

Precisely, Professor Serrano Oceja shows in this essay a natural mixture between his facet of historian and religious communicator, achieving an acceptable synthesis both for his writing style and for the diverse treatment of the issues.

The 19th century

Indeed, the book begins with an extraordinary exposition of the relations between Church and State in the 19th century, the most complicated century in our history. On the one hand, it describes that part of the history of the 19th century by focusing on the relations between conservative liberals and progressive liberals and their constant reflection throughout the century in their common animosity towards the Catholic Church. They really practiced from the power the de-Christianization of a country that had not been crossed by the true enlightenment.

The crumbling of confidence in the Church, the gradual destruction of Catholic arguments in social and cultural life will become increasingly noticeable.

They tried to change the way of thinking by means of Constitutions, changes of government, scorn in the press, in theaters and through blasphemies and, above all, an atrocious anticlericalism mixed with successive disentailments that left the Spanish Catholic Church unable to exercise charity with the needy or to provide for their most precarious needs.

Twentieth century: first half

Since the arrival of the twentieth century and Krausism forming a new intellectuality, more and more accentuated steps will be taken to lead to a civil war of extermination and fraternal destruction. The country will be divided to the core, family by family and environment by environment.

Serrano Oceja's study of the 20th century and the Spanish Civil War is accurate, brief and forceful. Things could only happen as they did because everything was perfectly measured, to turn Spain into a test bed for what would be the emergence of ideologies and their confrontation to the death in the Iberian Peninsula first and then in the old European continent.

At the end of the Second World War, both Spain and Europe were rebuilding and Spain was delayed by the presence of a dictatorship and the connivance of the Church with a regime that had no other weapons to sustain itself than to avoid political freedom at all costs.

Twentieth century: second half

Beginning in the 1960s, the book becomes a study of the bishops' relations with a regime that was being defeated by the culture and in the streets, both in the university and in the working class that turned its back on it.

As stated by Professor Julio Montero, both intellectuals and liberal professionals lived on the margins of politics, until the dictator's death when they took power.

The documentary basis with which the author faces the second part of the book, from the Second Vatican Council to the present day, is taken from the essay published in 2016 with Pablo Martín de Santa Olalla (Encuentro, 294 pp). Hence, the certainty with which he expresses, especially, the difficult situation of the Church with the governments of Felipe González, above all, in matters of education.

The Joint Assembly

In the first place, we must praise the delicate treatment of the Joint Assembly of bishops and priests that would conclude in September 1971 and whose minutes Cardinal Tarancon would hand-deliver to Paul VI himself before the beginning of the Synod of Bishops that year.

The phenomenon of the contestation and the manipulations of the voting achieved conclusions that did not correspond to the thinking of the majority of the clergy but of some who would end up abandoning the priestly ministry.

The author makes an effort to try to rush responsibilities and to approach the origin of the division of the clergy in Spain and the beginning of an animosity of part of that clergy against Opus Dei, on account of the question of the "Roman document". Clearly, the same people who capitalized on the maneuver ended up suppressing the condemnation of the Dicastery of the clergy, in exchange for burying the Conjunct.

Logically, Serrano Oceja, avoids entering into the phenomenon of the protest that took place after the conclusion of Vatican II and which Pope Benedict XVI has summarized with the dilemma between the hermeneutic of continuity with the tradition of the Church and the hermeneutic of rupture, such as that of the neo-modernists who still exist today, metamorphosed into the "dictatorship of relativism".

Open questions

At the end of this work we must ask ourselves why the Church and, specifically, the bishops, have hardly any echo in public opinion and why their documents have lost interest and influence among Spanish intellectuals. Perhaps the explanation is due to the secularization of Spanish society, as Serrano Oceja reflects when he speaks of a society that successively voted for the PSOE, while receiving with great enthusiasm the visits of St. John Paul II to Spain. It could also happen that the Church should present with greater clarity its proposals to the problems from the Christian revelation and appealing to the Christian roots of Europe, as both John Paul II and Francis reminded us.