The Chinese hierarchy has never been very accepting of trips by top Vatican hierarchs. The last to go to China was then-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, eight years ago. McCarrick later fell from grace because of the abuse scandal in which he was embroiled, and was forced to resign from the clerical state. But he remained, after all, the last cardinal to arrive in China.

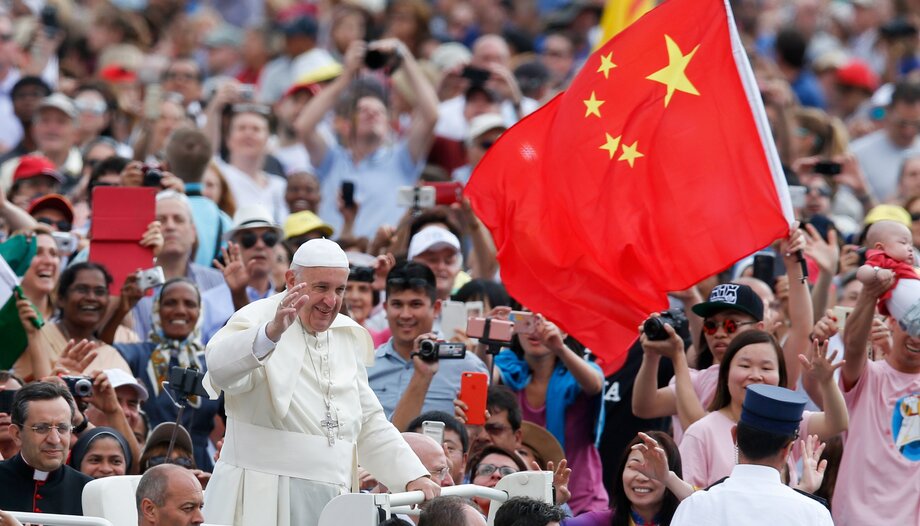

In the meantime, much has changed. In 2018, Pope Francis signed an interim agreement with China for the appointment of bishops. The agreement lasted two years, and was renewed in 2020 and 2022. It led to the appointment of six bishops with the dual approval of Rome and Beijing, although some of them were already in the process of approval before the agreement. But recently there has been a sudden acceleration on the Chinese side, which has put the newly renewed agreement in jeopardy.

Will Cardinal Zuppi's mission to China serve to strengthen the Sino-Vatican agreement? Or will it be of a different kind?

Red Dragon and geopolitical impact

Sending Cardinal Zuppi to China as the Pope's envoy would be the fourth expedition in a short time for the president of the Italian Bishops' Conference. The Pope had first appointed him his special envoy for Ukraine, and in that capacity Zuppi had gone first to Kiev, where he even met with President Volodyimir Zelensky, and then to Moscow, where he also met with Yury Ushakov, advisor to President Vladimir Putin.

Zuppi's was not a mission of peace, but of building bridges of dialogue. And the first form of dialogue was humanitarian engagement. Thus, the cardinal focused on the issue of Ukrainian children taken across the border. According to the Ukrainians, they were deported, torn away from their families. According to the Russians, they were taken home. However, no one knows the exact number. They are, in many cases, children without families, or unaccompanied, so it is difficult to have a precise number.

It seems that an agreement was finally reached on an exchange of lists between Ukraine and Russia that could lead to the eventual return of these children. But more work will have to be done on this agreement.

As part of the mission, Cardinal Zuppi traveled to the United States, where he also met with President Joe Biden. There, too, priority was given to humanitarian issues.

Why, then, China? Because the Holy See, or at least the Pope, looks with interest to Chinese mediation in the Ukrainian conflict. And, in this, the Community of Sant'Egidio, to which Cardinal Zuppi belongs, can be a good point of contact. Since Sant'Egidio has been one of the main promoters of the dialogue with China, it is among those who see the agreement for the appointment of bishops most positively, and therefore can serve as a bridge, even if interpretative, with China.

The agreement for the appointment of bishops

Although there is skepticism on the Chinese side that the go-ahead for Cardinal Zuppi's visit will actually come, there are some indications that it would be the right time to think about such a visit.

After the second renewal of the agreement for the appointment of bishops, two events occurred that soured Sino-Vatican relations.

Previously, the Chinese authorities had appointed the bishop of Yujiang, John Peng Weizhao, auxiliary of the diocese of Jainxi, which, by the way, is not recognized by the Holy See. The Holy See had protested, pointing out that this decision, taken without giving any information, violated the spirit of the agreement.

For this reason, the Chinese authorities unilaterally transferred Bishop Joseph Shen Bin from Haimen to Shanghai, installing him without any pontifical appointment. An irregularity that Pope Francis corrected after several months, making the appointment, but on which Cardinal Pietro Parolin also wanted to make an official pronouncement.

A two-way street between China and the Holy See?

Indeed, Cardinal Parolin's official interview following the appointment of Bishop Shen Bin by Pope Francis seemed to signal a two-track now in relations with China.

On the one hand, Pope Francis is determined to follow the path of dialogue, even pragmatically, healing any irregularities if they can be healed and proceeding on this bumpy terrain. On the other hand, there is a Vatican school that, while wishing to maintain a dialogue with China, wants this dialogue to be based on reciprocity.

The latest Chinese decisions stem from a restrictive interpretation of the agreement on the appointment of bishops. The agreement, they say, does not contemplate dioceses, and therefore China can decide to transfer bishops to dioceses even if they are not recognized by the Holy See, indeed, China even has the right to establish its own diocese. And the agreement, it is said, does not speak of transfers, although then the Chinese do not contemplate the idea that even a transfer from one diocese to another involves a papal appointment and a papal decision.

In fact, however, the agreement to work must be based on mutual understanding, and that is the most difficult challenge. On the part of the Holy See, the goal is that sooner or later the agreement will be published, making it definitive, because in this way a secure, or at least public, track should be established to which reference can be made. It will not happen immediately, but it is the most logical solution.

It was in 2005 that the then Secretary for Relations with States, Monsignor Giovanni Lajolo (now Cardinal), decided that the dialogue with China should be based in the meantime on a specific issue, which was the appointment of bishops. And in fact, following Benedict XVI's letter to Chinese Catholics in 2007, there were appointments that had the dual approval of Rome and Beijing. But even then, Beijing's decisions fluctuated, creating quite a few difficulties for dialogue.

What will Zuppi's trip be good for?

It is not known whether Zuppi's trip will serve to create a climate of confidence that will also allow the agreement to proceed on schedule. But that will certainly not be the objective. It would certainly help China gain greater legitimacy on the international scene, and this is believed to be a key element for the ultimate success of the mission.

If the Holy See helps the Red Dragon, and it succeeds, there could be developments. But at what cost, and how would the Holy See balance Chinese, Russian and Western interests? The risk is that of appearing too unbalanced toward one side of history, setting aside classic Vatican moderation in the name of a certain pragmatism.

The eventual mission of the cardinal Zuppi has to do with this balance. The challenges that remain in the background concern religious freedom, the Church's ability to exercise its mission, the Church's own freedom. But they also concern the position of the Church in this time of change.

Thus, the dual track of Vatican diplomacy also brings with it not inconsiderable challenges. Special envoys have always been part of the diplomatic effort. The important thing is not to abuse them, otherwise they become personalistic missions. Cardinal Zuppi's Chinese mission will also have to take this into account.