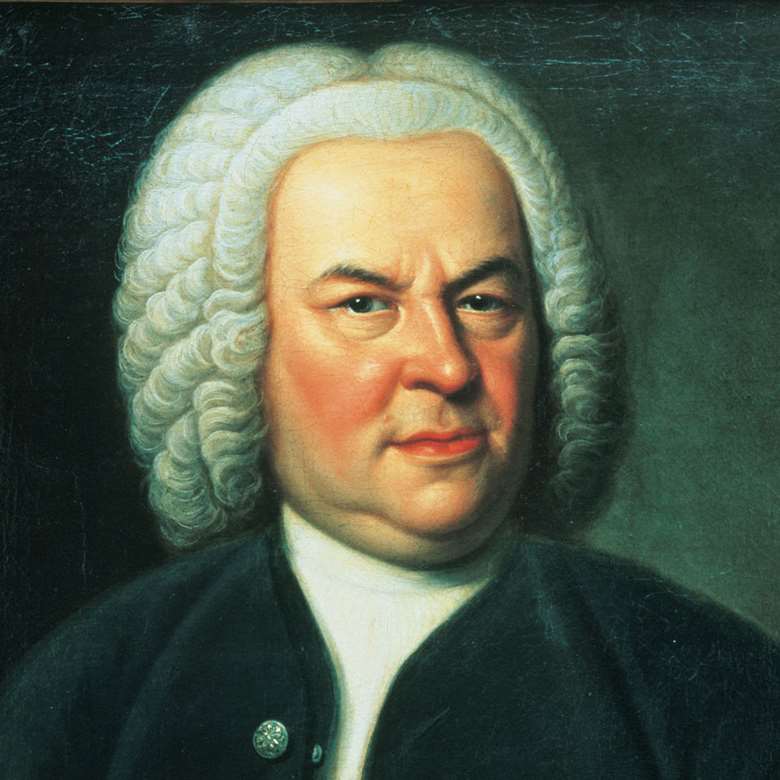

One of the earliest compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) is the cantata numbered 106 in the BWV catalog, whose title (taken from the first phrase of its text, as in all Bach cantatas) is "Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit" ("God's time is the best of all times"). As a unique feature, this cantata also bears the subtitle, or nickname, "Actus Tragicus", which is not due to the composer, but appears for the first time in a late copy of the score, made in 1768.

The cantata is usually dated 1707 or 1708, which is the period when Bach briefly held the post of organist at the church of St. Blaise in the Thuringian village of Mühlhausen. It is written for a small staff of players: four voices, two recorders, two violas da gamba and a basso continuo.

It is, therefore, the work of a first-time composer, who, at the age of 22, and about to marry his cousin Maria Barbara, is commissioned to compose this work for a funeral. As early as this cantata is, however, it is already a masterpiece, revealing for the first time its author as the musical genius he is. Only six early cantatas by Bach have survived, which gives this work additional value. Later, working in Weimar (from 1708 to 1717) and in Leipzig (from 1723 until his death), many more cantatas will come, of different form and style to those composed in his youth.

A biblical musical sequence

The form of this cantata is still very simple, consisting of a simple series of very short biblical texts on death. To a block of texts from the Old Testamentwhich contain reflections and warnings about death, follows a block from the New Testament, which expresses hope in the face of death and the spirit in which a believer must face it. The selection of the texts is possibly due to the young composer, who from his youth showed a wise veneration for the Word of God and Theology, as can be seen by examining the contents of his personal library. In particular, this cantata seems to be the musical echo of the Lutheran theology on the "Ars Moriendi", that is, the way to explain to the believer how to approach his duty to prepare himself adequately for the moment of death.

To this end, he arranges the sequence of texts as a brief (and tragic) Act of a sacramental auto sacramental, in whose protagonists the listener has to recognize himself so that the work can be heard with the meaning sought by the composer. In a continuous action, where the numbers are chained to each other, the listener will first hear the prophetic voices, which warn and admonish him, to later encounter the same "vox Christi" and end, with a chorale, listening to the voice of the believing assembly.

In the middle of the act is placed, like its heart, the intervention of the soul in the soprano, who in a heart-rending plea cries out for the coming of Christ and to hear his very voice. Preceding this whole ensemble, a short instrumental introduction that Bach composes as a prelude (as he will also do in many cantatas from Weimar and some from Leipzig) is a marvel.

Echoes of the Old Testament

Thus, the cantata consists of this sonatina, four vocal numbers on the Old Testament, an intervention of the soul, two numbers on the New Testament and a final chorus. In the sonatina we admire its homophonic simplicity and the tender nostalgia it evokes, far removed from the tragic effects of funeral compositions not as close to faith as this one.

In fact, over a simple flow of the violas and the basso continuo, the two recorders, an instrument traditionally associated with funeral rites, echo with a simple three-note motif, which leads to a major chord that gives way to the first vocal number.

This is a chorus that, after a sapiential sentence (the one that gives the cantata its title), and a small rhythmic gesture of the instruments (a joyful gavotte, to illuminate such a serious theme), gives way to a very lively chorus, in ternary rhythm, on the text "in Him we live, we move and we exist" (Facts 17, 28).

A dramatic contrast introduces a second sapiential idea: we live the right time that God has determined. The chorus falls silent after the words "when He wills". In a few bars, then, the listener moves from joyful reflection to tragic realization, passing through the reminder that the whole flow of life is done "in Him".

The second number, an arioso for tenor, illustrates Salt 90, 12: "Teach us to reckon our years so that we may acquire a sound heart". The voice of the psalmist David intertwines with the two flutes, over the accompaniment of the two violas de gamba and the continuo, to exhort us not to neglect the duty of every believer to acquire a sensible preparation for the moment of death.

Suddenly the bass guitar that stars in the third number bursts in, taking the voice of the prophet Isaiah to sing "prepare thy house, for thou shalt die and not remain alive" (Isaiah 38, 1). This is the prophet's warning to the dying King Hezekiah, with whom the listener must identify himself, so that, just as Hezekiah recovered by believing the prophet, the Christian overcomes death through his faith in Jesus Christ.

The uneasiness that these words would arouse in the king is represented by the restless rhythmic figure repeated by the flutes, this time without the tenderness of the violas da gamba, and which remains resounding when the voice falls silent.

Without interruption, the chorus takes the voice of the wise man to sing "it is an eternal law that man must die" (Ecclesiastic 14, 17). The complex counterpoint woven by the choir becomes increasingly dense, deprived also of the timbre of violas and flutes. As if trying to get out of this oppressive web, the soul, whose voice is taken by the soprano, presents its anguished plea with the words "Yes, yes, come Lord Jesus" (Apocalypse 22, 20). With them the tenderness of the violas returns, but not for long, because the oppressive chorus repeats itself again and again, as if entangling the soul in the fear of death ("man must die"). The choir and instruments muted, in a brilliant dramatic gesture, the soprano sings a melody in free fall over the basso continuo, which ends with the words "come, Lord Jesus" in a whisper and without any accompaniment.

The voice of Christ

Before this cry of the soul, the luminous block of the New Testament opens. In the first place, the high place recalls the words of Christ at death, so that the soul can make them its own: "Father, into your hands I commend my spirit" (Lucas 23, 46). It is a serene melody, accompanied only by the basso continuo, as was the soprano at the end of the previous number, which also sings with hope "You, the loyal God, will deliver me" (Psalm 31:6).

The endearing violas da gamba return when the bass appears bringing the same "vox Christi," who himself consoles the soul by singing "Today you will be with me in paradise" (Luke 23:43). As he will do later in the Passion according to St. Matthew, the musicalization of Christ as a bass accompanied by the strings offers a representation that brilliantly synthesizes the divine power of Christ with the tenderness of his humanity.

As is typical of early cantatas, when the bass repeats its intervention it does so over a chorale melody, sung by the alto and accompanied by the violas da gamba. The chorale sets to music a short verse written by Luther on Zechariah's canticle "Now you may let your servant go in peace".

The number ends with this chorale floating over a rich counterpoint elaborated by the two violas on the continuo, as if letting you savor this certainty of peace and joy that remains in the soul after everything experienced in this Act.

Finally, we must offer the God who has redeemed us from sin and has changed our anguish in the face of death into hope, the gratitude and praise that he deserves. For this, the recorders return to accompany the choir and the whole instrumental ensemble in a glorification of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, again with the danceable rhythm of the gavotte, underlining the joy and strength that the believer receives from his faith. And since that strength comes from Jesus Christ, this final chorus leads to a fugue full of life and movement, ending with the liturgical words "Through Jesus Christ, Amen."

The surprising ending of this chorus is not revealed here, so that each listener can discover it for himself. For this purpose, a good recording of the Russian ensemble "Bach-Consort" can be used, in which, in addition to listening to this wonderful cantata, it is possible to visually follow the interventions of the various voices and instruments.

Doctor of Theology