The Passion of Christdirected by Mel Gibson, was released on Wednesday, February 25, 2004, Ash Wednesday of that year. The film was preceded by a stubborn controversy, with accusations of anti-Semitism and extreme violence. The day after the premiere, The New York Timesprophesied that this film would mean the end of Gibson's professional career and called for an outburst to boycott it.

However, the reality was very different. On its first day, the film grossed $26 million (almost the total of what it had cost) and, by the end of its first week in theaters, it had surpassed $125 million.

Almost a month later, with a gross that already exceeded $200 million. The New York Times ended up admitting that The Passion had awakened Hollywood's hunger for religious films. No wonder: at the end of its theatrical run, this unique feature film grossed $370 million in North America and $251 million in the international market, making it the highest-grossing "R" rated film in the history of cinema (a record it still holds, by the way).

A personal motivation

In an interview published on the occasion of the premiere of Hamlet (1990), directed by Franco Zeffirelli, Mel Gibson - who played the Danish prince - already spoke of his desire to bring the life of Jesus to the screen and even to embody him himself.

At 34 years old at the time, the New York actor and director was going through a crisis of faith and felt the need to delve into the figure of Jesus and his sufferings, to understand how great his love for mankind was. "I have always believed in God, in his existence. But in the middle of my life I put my faith to one side and other things took its place. I understood then that I needed something else, if I wanted to survive. I was driven to a more intimate reading of the Gospels and that's where the idea began to take hold inside my head. I began to imagine the Gospel very realistically, recreating it in my own mind, so that it would make sense and be relevant to me. Christ paid the price for our sins. Understanding what he suffered, even on a human level, makes me feel not only compassionate but also indebted: I want to repay him for the immensity of his sacrifice.

This wish could not come true in the short term. It would be twelve years before his dream came true. In fact, Gibson shot The Passion in Italy between October 2002 and February 2003.

He had co-written the screenplay with Benedict Fitzgerald based on the Gospels and inspired by the plays The mystical city of Godby the venerable María de Jesús de Ágreda (XVII century) and in The sorrowful passion of Our Lord Jesus Christa book by Clemens Brentano detailing the visions of Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerick (18th-19th century).

Neither Gibson nor his team imagined the extent to which they would be rowing against all odds. And not only tide: a real storm was going to break out over them from the very moment the project was announced to the press.

First accusation: anti-Semitism

The first campaign against it focused on the accusation of anti-Semitism, a particularly serious accusation in a country like the United States and in an industry like Hollywood.

The script was leaked in a self-serving manner and found its way into the hands of official representatives of Judaism. Gibson was accused of promoting hatred of Jews, portrayed as responsible for the death of Jesus. This fear was picked up by a multitude of influential rabbis and spread throughout the country, labeling the film (before seeing it) as a threat to the Jewish people.

It is true that a well-known rabbi, Daniel Lupin, denounced the hypocrisy of his fellow countrymen of race and religion: "I believe that those who publicly protest against Mel Gibson's film lack moral legitimacy. Perhaps they don't remember Martin Scorsese's film, The last temptation of Christreleased in 1988. Almost all Christian denominations protested to Universal Pictures about the release of a film so defamatory that, had it been made about Moses or, say, Martin Luther King Jr., it would have provoked nationwide outcries of anger.

As it was, Christians had to defend their faith all alone, with the exception of the occasional brave Jew (...). Most Americans know that Universal was run at the time by Lew Wasserman and they were well aware of his [Jewish] ethnicity. We may wonder why Mel Gibson is not entitled to the same artistic freedom granted to Wasserman."

Although Gibson and his team tried to appease tempers by arranging private passes for Jewish opinion leaders, the sentence had been passed and was not going to be retracted.

An eventful shoot

With this rarefied atmosphere, it was time for filming. Gibson had no choice but to produce the film independently, as no major Hollywood studio wanted to get involved in the project.

Filming took place in Italy, at the well-known Cinecittà studios in Rome and at various locations (Matera and Craco, both in the Basilicata region). The production cost was around US$30 million, plus an additional US$15 million in advertising and marketing expenses, all of which was borne by Gibson and his production company, Icon Productions.

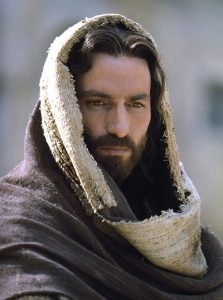

Anyone who works in film production knows what a shoot is like and, in particular, how unforeseen events are the order of the day. However, any keen observer would have noticed, in the case of this feature film, the extent to which incidents were becoming suspiciously frequent, especially in relation to Jim Caviezel.

Not only was the lead actor struck by lightning during the filming of the Calvary scene (as was another crew member), but he suffered several injuries while filming the scourging sequence and even a dislocated shoulder in one of the falls while carrying the cross.

During filming, he lost almost twenty kilos and subsequently had to undergo two open-heart surgeries. More than one wondered if there was someone out there determined that this film should not go ahead?

Second charge: extreme violence

If the accusation of anti-Semitism had not succeeded in boycotting the project a priori, the accusation of extreme violence was going to try to do so a posteriori. More than a few film critics even branded it as pornographic violence.

Spain was not an exception: "A despicable film (...) Gibson turns the one who judges his God into a wimp of a horror film of the high and refined business", wrote Ángel Fernández Santos in the pages of El País. "The Passion of Christwhich could well be titled The torture or lynching of Christto honor its true content (...). There is more of morbidity and sadism than of reconstruction of reality", wrote Alberto Bermejo in El Mundo.

There is no doubt that The Passion is a film that shows raw, stark violence, but not gratuitously, but properly contextualized. In an article commemorating the twentieth anniversary of its premiere, published in the National Catholic Registerscreenwriter and film critic Barbara Nicolosi comments: "The violence inflicted upon Christ in The Passion is certainly a terrible thing to behold. When I once remarked to Gibson that perhaps the violence in the film was too much, he shook his head and replied, 'It's not as much as a single mortal sin'. He was right, of course. Sin is what violated the body of Christ, and still violates the Mystical Body of Christ today. The aim of any meditation on the Passion is to provoke horror at the violence of sin. Gibson did it in his own way in this film". In the words of Juan Manuel de Prada, "in this rotten world, the use of violence is admissible if it is used to illustrate an anti-fascist or anti-war plea; on the other hand, it is scandalous in a Christian plea".

For his part, Gibson says: "If we had filmed exactly what happened, no one would have been able to see it. I think we've gotten used to seeing pretty crosses on the wall and we forget what really happened. We know that Jesus suffered and died, but we don't really realize what that means. I didn't realize until now how much Jesus suffered for our redemption either." However, the director decided to remake the film by cutting five minutes of film, which included the most unpleasant and explicit shots, and it was released in March 2005.

Seeking support

As the film continued to stir controversy, 20th Century Fox - the studio with whom Gibson was under contract and with whom he had produced and distributed his previous features (including the Oscar-winning Braveheartin 1995)-decided to disengage.

Faced with such a refusal, and in order not to embarrass the other major Hollywood companies, the director opted to distribute it on his own in the United States, with the help of a smaller company, Newmarket Films.

Aware that it was a film nicheThe project, for a very specific audience, sought the support of like-minded groups, both Catholic and Protestant. Many responded enthusiastically. The film's producer, Steve McEveety, even went to the Vatican to arrange a private screening for the Pope (John Paul II) and other authorities in the Curia. However, this initiative was partially truncated, as they did not receive approval to use any literal commentary from the Roman Pontiff.

There were steps forward and backward, and everything got tangled up when it shouldn't have. With great disappointment, Gibson and McEveety watched as those who should have been most supportive were elusive for fear of being caught in the eye of the hurricane.

A classic is born

After all this obstacle course, the film finally arrived in theaters. The enormous influx of public closed the mouths of some and rewarded the audacity and effort of others. More than one thought that what comes from God always manages to emerge and demonstrates in due time its power and efficacy.

While some critics responded in derision or anger, there were also those who recognized the greatness of the film from a formal and content point of view.

In Spain, Oti Rodriguez Marchante, critic of the ABCHe admitted: "A great filmmaker who has never once fallen into the expected scene, the easy composition, the visual cliché or the ready-made postcard (...) Whatever may be said, The Passion of Christas Mel Gibson sees and teaches it, is not only painfully physical and deeply spiritual, it is also unique.

On the other hand, in the pages of Row SevenJavier Aguirremalloa prophesied: "Any great film is a perfect conjunction of form and substance. Certainly, Gibson's film is impeccably made. I think that in a few years The Passion of Christ will be considered a masterpiece, one of those essential films in the history of cinema".

Indeed, the film is of exceptional quality both in what it narrates and in the way it does it. The images and sound convey in a naked, realistic way - far from any pietism - the sequence of the arrest, trial and execution of Jesus of Nazareth, in a successful and difficult balance between rawness and contemplation. Not in vain, Gibson himself preferred to refer to it "less as a film as such and more as a journey through the Stations of the Cross".

An icon in motion

Caleb Deschanel's photography paints the screen with chiaroscuro (in the manner of Caravaggio) in a palette of ochre and muted tones, thus achieving a beautiful drama, while John Denby's music envelops the scenes with a solvent soundtrack that accentuates it in a non-intrusive way.

At the same time, it is the restrained performances, tailored to each character, that are the most effective windows through which the viewer relives the drama of Calvary: a Jim Caviezel who offers an empathetic, close and majestic Jesus, whose face and body progressively become a tableau of sorrows; Maia Morgenstern who embodies a pietá of flesh and blood, in whose heart love and pain merge in a touching acceptance; a Monica Belluci who combines beauty and misery, a living image of fallen and redeemed nature... The real antagonist, Satan, who is brought to life by Rosalinda Celentano (demon-adult) and Davide Marotta (demon-child) in a strangely seductive and grotesque portrayal, a reflection of temptation and the deformity of sin, deserves a special mention.

The alternate montage - the work of John Wright - which combines the hardest moments of the Passion with those of the Passion of Christ. flasbacks of Jesus' life (with his Mother in Nazareth, at the Last Supper) that relieve the painful dramatic tension and act as breathers for the suffering spectator. And also, of course, the brief final coda of the film, which masterfully narrates the Resurrection, because Redemption, in Tolkien's words, is the primordial eucatastrophe, as Joseph Pierce rightly points out in his assessment of this film.

It is this same British writer who summarizes: "It is inadequate to describe Mel Gibson's masterpiece, The Passion of ChristIt's much more than that. It would be more accurate to describe it as an icon in motion. It calls us to prayer and leads us to the contemplation that brings us into the presence of Christ himself. (...) As T. S. Eliot says about The Divine Comedy of Dante: there is nothing to do in the presence of such ineffable beauty except to contemplate and be silent".

A film that transforms lives

Time has shown that The Passion of Christ not only can it be called a masterpiece, but it is more than just another film about the life of Jesus.

Since its premiere two decades ago, the torrent of individual and collective catharsis has not ceased to flow, in a similar way to how - in the sequence of Calvary - water and blood flow forcefully over the Roman soldier who opens the side of the dead Christ, and falls to his knees under that stream of grace. If anything, this film leaves no one indifferent.

Numerous testimonies of conversions - large and small - have been appearing here and there... A plethora of stories with a common denominator: the experience of having experienced as never before the sufferings that the Son of God endured to save us.

Conversions during the filming (the cases of Pietro Sarubbi, who plays Barabbas, and Luca Lionello, who plays Judas Iscariot), and many others among the public who came to see it. In the United States, the documentary film Changed Lives: Miracles of the Passiondirected by Jody Eldred with several testimonies on the subject (also published as a book).

To what extent does this cinematic work act as an instrument of grace? Mel Gibson points to an explanation from his own experience: "This film is the hardest thing I've ever done. Watching it is even harder, because the Passion of the Christ was. But in making it, I found that it actually purged me. In a way, it healed me (...) My goal is that whoever sees it will experience a profound change. The audience has to experience this harsh reality to understand it. I want to reach people with a message of faith, hope, love and forgiveness. Christ forgave us even when he was tortured and killed. That is the ultimate example of love.

This is precisely what Gabriela and Antonio experienced. She is a fashion designer in Valencia, and this is her testimony: "At the age of 13 I stopped practicing my faith. I left God in Heaven; I didn't dare to look at Him much, because then I could do whatever I wanted. But since God is very good, the TV changed my life". It happened a few days before Easter. She was alone at home, bored, and sat down in front of the TV. When she turned on the TV, she found that the movie of The Passion. While seeing her, he recalls, "the Lord changed my heart and my mind; he made me understand what he loves me, what he has done for me, and to realize how I was turning my face away from him since I was 13 years old". He decided to go to confession after several decades and return to going to Mass on Sundays. "I experienced my first Palm Sunday after a long time, with the feeling of coming home and with tremendous joy," he recalls.

Antonio's case is very similar. A university professor in Seville, agnostic and anticlerical, he went to the cinema with his wife to see a film in original version (she is an English teacher). On that day there were no films on offer, but they were screening The Passion. "We walked in with no idea what the movie was about, or that Mel Gibson was directing it," he recalls. There were no more than fifteen people and as the movie started, with the scene of Jesus' agonizing prayer on the Mount of Olives, he was completely absorbed. "I began to feel a lot of pain for my sins and then the gift of tears..... It was not hysterical weeping, but hot tears, which soaked all over my shirt and ran down my pants. When the film was over I felt transformed and thought: 'all this was true, you suffered for me!'"

The list of testimonials would be endless. It is understandable that Barbara Nicolosi, establishing a relationship between the difficulties that the film experienced in its production and the impact among people all over the world, concludes: "The Passion is a miracle.

Final balance

The two decades that have passed confirm the peculiar nature of this film, which can be defined as a cinematographic icon (a work of art that leads to contemplation) and even as an example of "sacramental cinema" (a channel or vehicle of grace). Hence Barbara Nicolosi's unequivocal statement: "After twenty years, once the dust raised by the culture war has settled, it can be clearly and indisputably stated that The Passion of Christ is the greatest work of sacred cinema ever made".

Was it worth it? Mel Gibson and Jim Caviezel, as well as producer Steve McEveety, have no regrets. Quite the opposite, in fact. Of course, they were aware of the risk they were taking. Indeed, the careers of both actor and director were cut short by this production. Gibson, who had achieved glory with BraveheartCaviezel, whose promising trajectory seemed to be affirming itself after The thin red line (1998) y The revenge of the Count of Monte Cristo (2002) would see his name relegated to second tier titles (until the recent Sound of Freedom, 2023).

Their names may not appear again in major motion pictures, but they have reason to believe that they are written in Heaven....

Priest. Doctor in Audiovisual Communication and Moral Theology. Professor of the Core Curriculum Institute of the University of Navarra.