Father Giussani, founder of Communion and Liberation (CL) in the 1960s in Italy, died on February 22, 2005 in Milan, after living an "essential" Christianity - as Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis would emphasize decades later, his biographer pointed out - and extending the movement to some ninety countries on five continents.

October 15 marked the 100th anniversary of his birth in 1922, and thousands of CL members filled St. Peter's Square for a meeting with Pope Francis. The Holy Father expressed, among other things, his "personal gratitude for the good he did me, Giussani, when I was a young priest; and I do it also as a universal Pastor for all that he did in his life. knew how to sow and radiate everywhere for the good of the Church...".

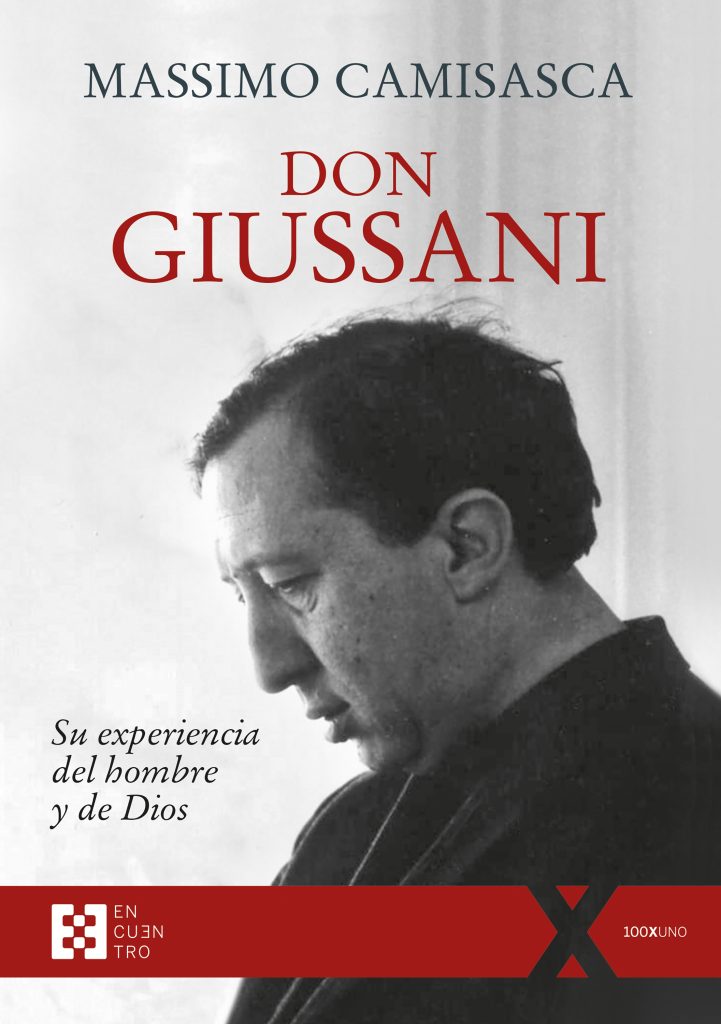

Last weekend, Monsignor Massimo Camisasca delved into the charism of the Founder at the presentation of the Spanish edition of his book, entitled "Father Giussani. His experience of man and God"in an event moderated by Manuel Oriol, director of Ediciones EncuentroThe historian Ignacio Uría also participated.

As he explains in this interview with Omnes, Bishop Camisasca met the Servant of God Luigi Giussani in 1960, when he was 14 years old, and was at his side for the next 45 years of his life. He is, therefore, a particularly authoritative biographer to speak about the life and thought of the founder of Communion and Liberationabout which he spoke a few months ago in Omnes Davide Prosperipresident ad interim of Communion and Liberation.

Before offering his answers, we take up an idea that Monsignor Camisasca launched during the presentation: "In addition to being a genius of the faith and of the human, Giussani was also a genius of the Church. He led those who followed him to identify with the method of God's manifestation in the world: God addresses himself to some in order to speak to all; he begins with a small seed, a small flock, but he wants all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. For Giussani, the experience of election, which was at the heart of his educational method, was never the affirmation of an enclosure, but the affective center of an ecumenical openness.

At what point did you think of writing this biography about Father Guissani? Were you able to meet him and get to know him? What were your first impressions when you met him? Were you already a priest and bishop, or still a layman?

- I met Fr. Giussani when I was fourteen years old, in 1960. Giussani, who had been ordained a priest fifteen years earlier and had left the seminary to teach theology, began to teach religion in order to be in contact with young people and to foster the rebirth of the Christian faith in their hearts.

I was at Fr. Giussani's side for the next forty-five years of his life. Naturally, in different ways: first as a student, then in charge of following the birth of the Movement that was taking its first steps; later, as a priest, in charge of following relations with the Holy See and especially with John Paul II in Rome; finally, at his request, as founder of the Priestly Fraternity of the Missionaries of St. Charles.

When Father Giussani died, I immediately thought of compiling a synthesis of his thought in a small book. Thus was born this text in which, following a chronological order, I try to express in a simple but complete way, the most important reflections he expressed throughout his life.

"The Church recognizes his pedagogical and theological genius, deployed from a charism given to him by the Holy Spirit for the common good," said Pope Francis of Father Giussani at St. Peter's. Do you deal with these aspects and his charism?

- Deede then. Giussani's charism can only be grasped by following his life and writings and by getting to know the people who followed him. In this book, therefore, one can grasp the centrality of the mystery of the Incarnation, of the event of the Word of God made man, which moved Father Giussani, when he was fourteen years old, to see in the person of Christ the center of the cosmos and of history, as John Paul II would later say. The heart of every human expectation, of every desire for happiness, beauty, justice and truth.

When he was still a seminarian, this perception of the Incarnation as a central event in the history of the world impressed Father Giussani to such an extent that it became the burning heart of his whole life, of all his reflection and of all his educational work.

Deep down, he wanted to be nothing more than a great witness to the human fullness that happens in those who follow Christ, in those who abandon everything to follow him and to find in him the hundredfold of the things they thought they had left behind forever, purified and made eternal by love.

At the same meeting in Rome, the Pope referred to the "educational and missionary passion" of the founder of the movement. His biography is presented as "intellectual", and also as "spiritual". Correct?

- The editor wanted to capture the two main aspects of my writing. It is an intellectual biography because it does not dwell on the external events of Father Giussani's life, but on the itinerary and maturation of his thought. It is a spiritual biography because it wants to show the path that Christ made in Father Giussani and the path that Father Giussani made in the world to make possible the encounter with Christ of the younger generations and then of adults.

Giussani's great desire to "evangelize culture" has been underlined. How do you address this concern of the Founder? The then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger Giussani grew up in a house-as he himself said-poor in bread, but rich in music. Thus, from the beginning he was touched, indeed, wounded, by the desire for beauty (...) He sought beauty itself, infinite Beauty".

- Father Giussani loved the human. Not only man, but also everything that was the work of man. He loved literature, poetry, music. He loved, in short, the expressions of life. These were also the ways through which he reached the people. He spoke of Christ playing a Brahms, a Beethoven or a Chopin. He found traces of Christ, or of his waiting at least, in the poetry, for example, of Leopardi. He quoted countless great literary authors of all times, to help us see the imprint, the sign of the divine, within the genius of man.

In this way, he opened the lives of those who followed him to curiosity, to a healthy curiosity for everything that lives in the Universe and speaks to us of the Mystery. Culture, for Giussani, did not at all mean the accumulation of knowledge, but, on the contrary, the ability to relate to everything that is alive and human and that carries within itself the question of the infinite.