On January 18, 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor. Otto von Bismarck had achieved the goal of unifying Germany into the Deutsches Reich, a goal he had been pursuing for decades. However, both the Chancellor and many of his contemporaries perceived that the new empire faced internal threats. For Bismarck, the main danger to the national unity of the Prussian-Protestant empire lay with the Catholic Church.

Prussia had always been a Protestant territory, right from its origins. The Duchy of Prussia, founded in 1525 by the former Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Albrecht Albrecht, after converting to Lutheran Protestantism, was the first European principality to adopt Lutheranism as its official religion. This tradition was maintained when the Duchy was inherited by the Hohenzollerns of Brandenburg in 1618, where Lutheranism had also spread. Thus began the rise of Prussia-Brandenburg until Prince Elector Frederick III of Brandenburg was crowned King. at Prussia in 1701. The title refers to the fact that part of Prussia - belonging to Poland - was outside its territory. The title King of Prussia will begin to be used after the annexation of the former Polish Prussia in 1772. In any case, Protestantism was part of Prussia's identity, as opposed to the Catholic character of the other kingdom descended from the Romano-Germanic Empire, that of Austria.

At the beginning of the 19th century, practically all Catholics living in Prussia were of Polish origin: from the former Polish Prussia or from the Silesia that had been annexed by Frederick II (1712-1786). This situation changed markedly when, after the Napoleonic wars, a large part of the Rhineland and Westphalia became part of Prussia, since 70 percent of the population there was Catholic.

In Prussia, as in other Protestant German states, the sovereign served as "summus episcopus" (supreme bishop) of the Protestant regional churches. The Prussian General Land Law of 1794 provided that religious practice, both public and private, was subject to state supervision. But this state supervision over the Catholic Church in the Rhineland and Westphalia came into direct conflict with the universal authority of the Roman Catholic Church.

ZdK precursor associations

In order to resist in this hostile environment, Catholics began to organize politically in Prussia: as early as 1848 an attempt was made to unite the "pious associations", which led in 1868 to the founding of a "Central-Committee", the precursor of the "....ZdK"("Central Committee of German Catholics"), after World War II.

Simultaneously, in 1870 a confessional political party, the "Zentrum", was formed, which the following year became the third parliamentary group in the Reichstag. Bismarck accused them of being "ultramontane"; that is, of following the directives of Rome, where Pope Pius IX rejected liberalism and the secular state.

For this reason, anti-Catholicism was widespread among supporters of liberalism in Prussia and throughout Europe. By attacking Catholics, Bismarck secured the support of liberal journalists and politicians in the National Liberal Party (NLP), the dominant political force in the new Reichstag and in the Prussian House of Representatives.

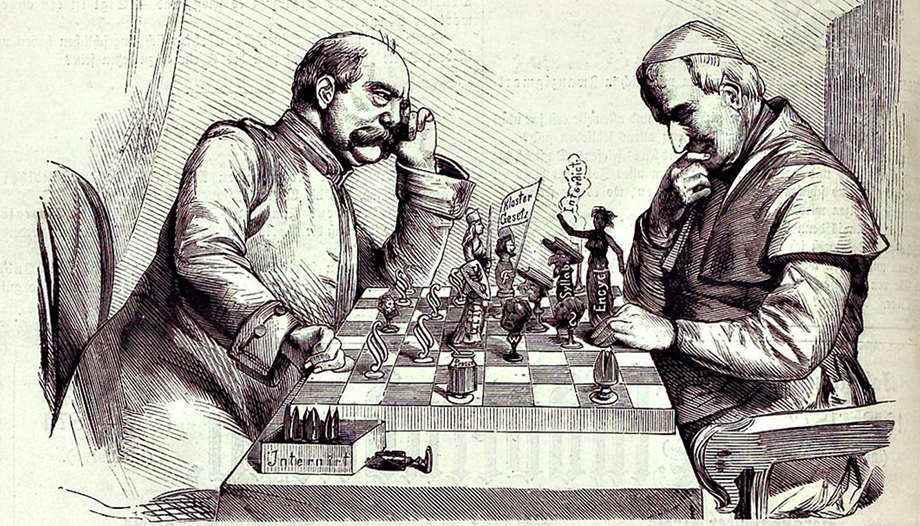

The Kulturkampf

One of the first direct actions against Catholics was the "pulpit decree" (Kanzelparagraph) of December 1871, which threatened with imprisonment clergymen of any denomination who commented on state affairs in the exercise of their office. This marked the beginning of the Kulturkampf, a term coined by the left-liberal politician and famed physician Rudolf Virchow.

The repressive measures continued: in 1872 the Jesuit order was banned, while the "School Supervision Law" of 1873 placed all schools under state control; in 1875 civil marriage was introduced as the only valid form of marriage and all those religious orders that were not exclusively dedicated to the care of the sick were banned.

At the same time, surveillance and control over Catholic associations, the press and religious education was intensified. In the first four months of 1875 alone, 136 Catholic newspaper editors were fined or imprisoned. During the same period, 20 Catholic newspapers were confiscated, 74 Catholic buildings were searched, and 103 Catholic political activists were expelled or interned. Fifty-five Catholic organizations and associations were closed.

By the end of the 1870s, the Catholic Church had lost considerable influence and its situation in the German Reich was bleak: more than half of the Catholic bishops in Prussia were in exile or in prison, and a quarter of Prussian parishes were without a priest. By the end of the "Kulturkampf", more than 1,800 priests had been imprisoned or expelled from the country and church property worth 16 million gold marks had been confiscated.

However, Bismarck's policy had the opposite of the desired effect: the cultural battle strengthened the solidarity within the Church, between the hierarchy and the laity of the Central-Committee, as well as the link with the Pope and the identification with the papacy.

Conflicts of interest between liberal and conservative Catholics took a back seat.

Catholic associations experienced a major boom, as did the Catholic press, which strongly supported the Zentrum's policy despite repressive measures. In the 1878 Reichstag elections, the Zentrum established itself as the second largest parliamentary group, winning almost the same percentage of votes as the National-Liberal Party: 23.1 percent each, which translated into 99 seats for the NLP and 94 for the Zentrum out of 397.