Translation of the article into Italian

Seventy-four years of history elapsed between the fall of the Empire of the Czars in 1917 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. During that long period, the destinies of the USSR, stretching from the Urals to the steppes of Central Asia and the confines of Siberia, were decided by one leader.

Those who, on March 11, 1985, placed the Mikhail Gorbachev (Privolnoie 1931) at the pinnacle of power had no conscience to elect the last General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. At 54, he was the youngest member of the Politburo and, when the time came, a natural candidate to succeed the aging Konstantin Chernienko. For the first time in Soviet history, the Kremlin couple, Mikhail and his wife Raisa, four years younger, were not older than the White House.

Gorbachev's policy

Although not doctrinaire, Gorbachev was a communist convinced of the fundamental principles of socialist ideology, and he tried to maintain his commitment. Along with the policy of transparency (Glasnost), Perestroika was his great objective: reforming the system from within, and from above, without renouncing socialism.

Whether out of conviction or necessity, given the complicated economic and social situation of the USSR, from the beginning of his mandate he promoted rapprochement with the United States. The summit with Reagan in Geneva in November 1985 opened the way to détente. The new international climate made possible nuclear arms reduction agreements and an international thaw. History recognizes his role in the fall of the Berlin Wall, and in the non-violent transformations of 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe: he could have reacted Soviet-style, as in the Hungarian (1956) and Czechoslovakian (1968) crises, and chose to let the people go their own way in freedom.

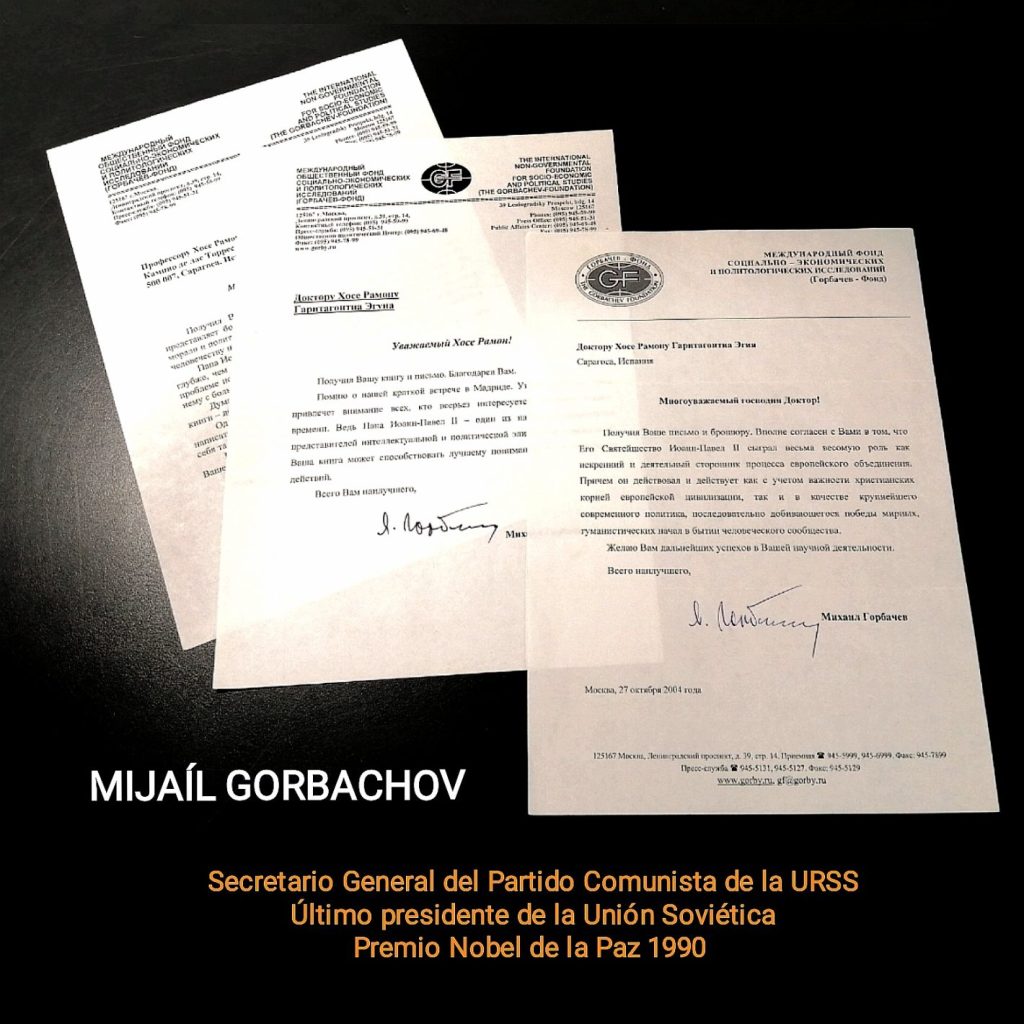

Gorbachev's decisive role in those events did not go unnoticed by another great protagonist of Europe's transformation: John Paul II. I devoted my thesis in political science to analyzing the influence of the first Slavic pope on those events, and Gorbachev accepted my invitation to write the book's introduction. Recently I have published a long article about their relationship. In those years I met personally with both of them, and I saw their mutual appreciation. Gorbachev records his admiration for John Paul II in the letters he wrote to me on the occasion of his thesis. Documents for history that I donated some time ago to the general archive of the University of Navarra.

The birth of a friendship

Since their first meeting at the Vatican, on December 1, 1989, a current of admiration and appreciation arose between them. Two decades later, spokesman Navarro-Valls recalled that, among all the meetings he had during the 27 years of his pontificate, "one of those that Karol Wojtyla liked most was the one he had with Mikhail Gorbachev.". On that day the spokesman asked John Paul II his impression of Gorbachev: he is "a man of principle," the Pope replied, "a person who believes so much in his values that he is ready to accept all the consequences that follow."

After the death of John Paul II, Gorbachev was interviewed on Radio Free Europe. The journalist asked, "Mikhail Sergeevich, you were the first Soviet leader to meet Pope John Paul II. Why did you decide at that time to request an audience?" The answer recalled the very special circumstances of that extraordinary year: "Many things had happened that had not happened in the previous decades. I think this is related to the fact that, in 1989, we had already come a long way."

Mutual trust

What facilitated the connection between the two personalities? For the last Soviet leader the key was in history and geography: they were both Slavs. "Initially," Gorbachev recalled after John Paul II's death, "to show to what extent the Holy Father was a Slav, and how he respected the new Soviet Union, he proposed that we spend the first 10 minutes alone together and he spoke in Russian. Wojtyla had prepared himself for the conversation, brushing up on the Russian language: "I have broadened my knowledge for the occasion." he said at the outset.

The relationship between the two personalities is a clear example of the 'social friendship' that Pope Francis describes in "Fratelli tutti"The verb "to draw near, to express oneself, to listen to one another, to look at one another, to get to know one another, to try to understand one another, to seek points of contact, all of this is summed up in the verb 'to dialogue'" (n. 198). John Paul II and Mikhail Gorbachev made the effectiveness of the encounter possible by their attitude. They showed their "ability to respect the other's point of view while accepting the possibility that he may hold some legitimate convictions or interests. From his identity, the other has something to contribute, and it is desirable that he deepen and expose his own position so that the public debate may be even more complete" (n. 203).

The memory of Gorbachev

The two Slavs were impressed by that conversation in the Library of the Apostolic Palace. They were struck by the rapport that emerged so naturally. "When the meeting took place," Gorbachev recalled years later, "I told the Pope that one often finds the same or similar words in my statements and in his. It was no coincidence. So much coincidence was a sign that there was "something in common at the base, in our thoughts." The meeting was the beginning of a special relationship between two personalities, at first very distant. "I think I can rightly say that during those years we became friends," Gorbachev wrote on the centenary of John Paul II.

With the passage of time the breadth of his revolution will be better understood, and will place Mikhail Gorbachev in his rightful place in the history of the 20th century.

D. in Political Science and Public International Law