The cruel war between Russia and Ukraine, the thousands of victims, the displaced, the destroyed cities and villages and the madness of increasingly terrible weapons that continue to massacre innocent people are at this point a story that repeats itself over and over again and humanity seems never to want to learn from its mistakes.

Of all the voices that have been raised in the name of peace in recent times, there is one, in particular, that seems to really care about peace itself, if only more than about gas, arms sales or sanctions. And we are talking about Pope Francis.

In fact, among the various world leaders, the Pope has tried, since the beginning of the conflict, to keep a diplomatic channel open with both sides, and he has done so with concrete gestures: personally going to the Russian and Ukrainian embassies, activating the apostolic nunciatures present in both countries, providing material aid and spiritual support, dialoguing with the political and religious leaders (Catholic and Orthodox) of Russia and Ukraine, including the Primate of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Moscow, Kirill, whom, in the face of the latter's Caesaropapist nudges to justify his country's aggressive policy towards Ukraine (especially in the famous virtual bilateral meeting between the Pope and the aforementioned patriarch), the pontiff (and let us remember here the etymology of that term: bridge builder) did not fail to recall that the task of ecclesiastics is to proclaim Christ, not to favor or oppose a temporal power, which was reiterated, at the time of writing, on May 6, 2022, when Francis, receiving in audience the participants in the plenary session of the Pontifical Council for Christian Unity, once again condemned the "cruel and senseless" war in Ukraine, declaring that, "in the face of this barbarism, we renew our desire for unity and announce the Gospel that disarms hearts in the face of armies."

However, there has been no shortage of criticism, from both Catholics and Orthodox, of the Pope for not taking an openly pro-Ukrainian stance in the current conflict.

Francis' attitude, however, is in perfect continuity, in this as in other cases (the war in Syria or the most recent protests in Myanmar are examples), with that of his predecessors, in particular John Paul II, in wanting to promote certain values of peace, solidarity and social justice throughout the world, regardless of country, ethnicity or religion. For this reason, he dialogues and seeks to establish relations with all governments, regardless of creed or ideology, which is also expressed through the concept of multilateralism, i.e. equidistance (perhaps, however, it would be better to say equidistance) with respect to the subjects involved.

In practice, all this is extraordinarily similar to what happened with Pius XII, the reigning Pope during the entire Second World War, who never openly condemned Hitler, although, continuing the policy of hard opposition to that ideology of Pius XI (who harshly condemned Nazism with the Encyclical "Mit brennender Sorge"), he intervened several times against Nazi policy with different messages, in particular with the Christmas message of 1942 and the consent of the reading of the famous Pastoral Letter "We live in a time of great suffering", written by the Dutch Episcopal Conference and read in all the churches of Holland on July 26, 1942 (in retaliation to which Hitler ordered the arrest and deportation of Jewish converts, until then spared from his fury, as Edith Stein, St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross).

The subject is quite complex, but equally interesting, since the role of the Catholic Church in national and international affairs is anything but secondary, if we think that it can influence, directly and indirectly, billions of people, not only among the baptized, but also among juridical subjects that can be individuals, States, supranational organizations and that have nothing to do with the faith professed by Catholics.

The need for diplomacy and recognition at the international level

The Holy See's diplomacy is heir to a millennia-old tradition, which has made the papacy the forerunner of modern relations between States, and it acts on two particular fronts: on the one hand, the protection of Christians, particularly Catholics; on the other, the promotion of the values of justice, peace and the safeguarding of human rights: its Ostpolitik, especially since the late 1950s, is a concrete example of this.

This realistic policy, which takes its impetus from Pope John XXIII's 1963 encyclical "Pacem in Terris" (in which the pontiff explains that world peace is an ideal to be pursued through dialogue and cooperation with all peoples "of good will", even with those who are carriers of an "erroneous" ideology such as atheism and communism), which will also condition the Holy See's international policy from Paul VI onwards.

It is necessary, at this point, to make an essential distinction between the Holy See and the Vatican City State: the first constitutes an abstract sovereignty, i.e. without a well-defined territory, of the Pope over the Catholic faithful (about one billion 345 million people, according to the Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae of 2019), but recognized by all international organizations; the second is, on the other hand, the smallest State in the world (its area is only 44 hectares), whose sole function is, by virtue of its creation in 1929 by the Lateran Pacts, to provide material and legal support for the activities of the Holy See, including the safeguarding of its cultural, artistic and religious heritage.

The Holy See and international politics

The Apostolic See, therefore, is the highest authority of the Catholic Church and is governed by the Supreme Pontiff (the Pope) and the Roman Curia, headed by the Secretary of State, who, under the authority of the Holy Father, is the head of the diplomatic structure. Because of its special status, it is the Holy See, and not the Vatican City State, which maintains diplomatic relations with other States and international bodies, and these relations require a large institutional organization.

Papal diplomatic officials, as well as apostolic nuncios and lay people who represent the papacy internationally, come from almost every state in the world and are trained at the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy, the Vatican's foreign policy school.

The purpose of contacts with civil society is to ensure the survival and independence of the Church and the exercise of its specific function (freedom to maintain contact with the center; freedom of movement and responsibility of bishops and priests; freedom of conscience and worship for all). In the absence of these basic conditions, diplomatic relations are normally not established (this is the current case in China, Bhutan, Afghanistan, North Korea and the Maldives).

The Holy See has a wide and capillary diplomatic network. In fact, it maintains normal diplomatic relations with 183 of the 193 UN member states and has permanent observer status at the United Nations, but not full membership, since it is the representative of a spiritual power that opts for total neutrality in international affairs.

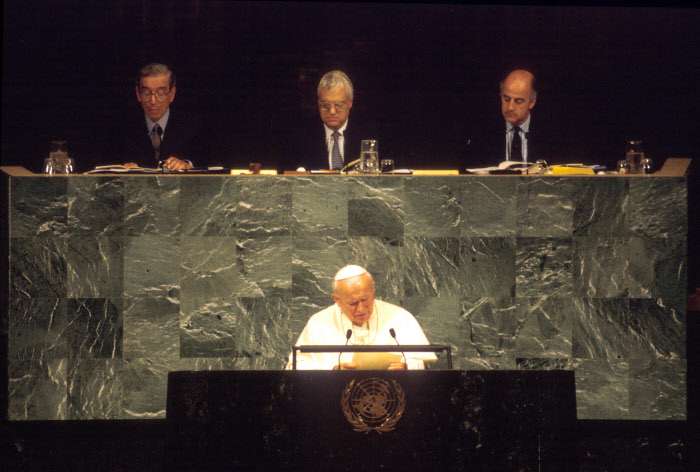

John Paul II and his international policy

The international policy of John Paul II is, of course, the most obvious one to take into account when analyzing the Holy See's concept of multilateralism in international politics, since the period of time it covers is remarkably broad and confirms the multiple and aforementioned objectives of the Holy See's action at the global level. John Paul II's pontificate, in fact, was characterized not only by its duration in terms of time (27 years), but also by the large number of important events that marked it, for example, the long dispute with the communist regimes, in particular that of Poland (his country of origin), the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the recognition of Israel and the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Jewish State in 1994, the repeated attempts to normalize relations with China and Vietnam, the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the historical dividing line between Orthodox and Catholics in the Balkans, which put Vatican diplomacy in serious trouble and led it to intervene directly in the matter in 1992, recognizing the independence of Croatia and Slovenia, traditionally Catholic nations.

Among the most interesting cases to mention, because of their similarity to current issues, is that of the Philippines, a country visited by John Paul II in 1981 and where the campaign of passive resistance (very similar to what is happening today in Myanmar) led by Cardinal Jaime Sin against Marcos resulted in the exile of the dictator in 1986; or Cuba, where, in 1998, the Pope clearly reiterated his opposition to the U.S. embargo and sanctions that had been suffocating the island's economy for 35 years, criticizing these retaliatory measures against a country by other states and accusing them, as in the case of Iraq or Serbia (similar to Russia today) of only harming innocent citizens without providing any definitive solution to the problems.

Finally, we would like to mention two particular cases in which, during the pontificate of John Paul II and following the intervention of John XXIII as mediator between the United States and the USSR in the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, the Holy See was particularly active in the search for peaceful solutions to conflictive situations in the international arena: In the first case, Wojtyla and his representatives, in particular the Apostolic Nuncio in Argentina, succeeded in averting the already imminent conflict between Chile and Argentina over the sovereignty of the Beagle Channel in 1984; in the second, during the international crisis that preceded the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the diplomacy of the Holy See acted in coordination with the representatives of France, Germany, Russia, Belgium and China at the United Nations to avoid armed conflict, and John Paul II even sent the Nuncio to Washington to meet with George Bush Sr. and express the Pope's total disagreement with an invasion of the Middle Eastern country, which unfortunately took place.

All these examples are remarkably reminiscent of more recent events and issues (Myanmar, Syria, the Russia-Ukraine war and its aftermath) and allow us to frame Pope Francis' international policy and his multilateralism, or "equivocity" with all parties involved in conflicts at the international level, as perfectly suited to the needs of the Holy See's diplomacy.

Writer, historian and expert on Middle Eastern history, politics and culture.