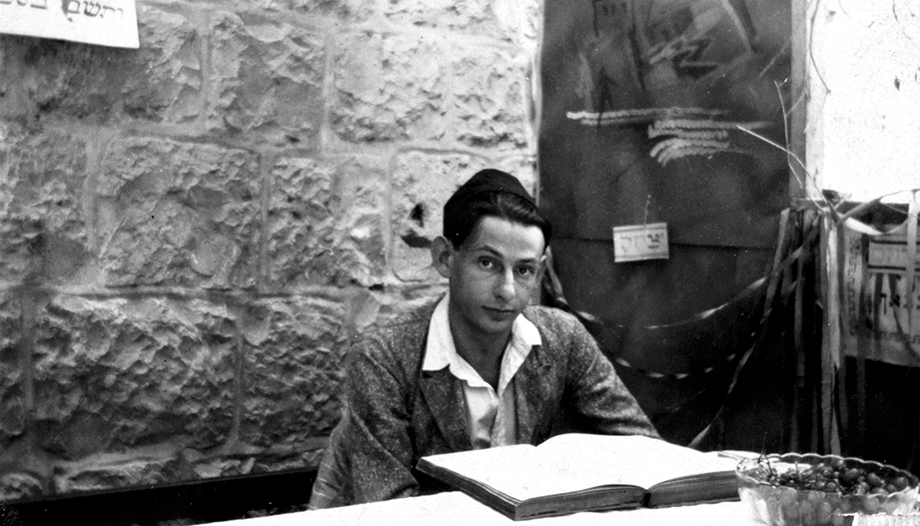

Gerhard Scholem did everything in his power to be as Jewish as possible. He was born in 1897 into an assimilated German-Jewish family, for whom Jewishness was nothing more than the traditions of their ancestors. Therefore, the young Scholem's quest was seen as an act of rebellion, a sign of his interests in the Jewish world. too Jews. Proof of this is his rejection of the name "Gerhard" and its replacement by the much more Jewish name "Gershom".

He studied mathematics, philosophy and oriental languages before finding his favorite subject of study: Kabbalah, the system of interpretation of the occult doctrines of the Jewish mystical tradition. He participated in Zionist groups from a young age. He claimed that for him Zionism was not only a political movement, in favor of the creation of the State of Israel, but a movement of profound renewal of Judaism.

For Scholem, Judaism was something particular, impossible to assimilate to any other culture without destroying itself; the search for that "true Judaism" was what moved him to study the Kabbalah and other historical movements, as well as to join Zionism and move to live in Jerusalem, where he died in 1982, after a prolific academic life at the Hebrew University. His interest in the spiritual renewal of the Jewish people led him to research on history, messianism and Jewish identity and historical mission.

His passion for the past was not merely a scholarly interest: what he hoped to find in history was the renewing force that would make it possible to build the present and thus give the Jewish people new reasons to struggle to exist. Thus he writes in Major trends in Jewish mysticism: "The stories are not yet finished, they have not yet become history, the secret life in them may emerge again in you or me today or tomorrow.".

Scholem considered that the irrefutable proof of the particularity of the Jewish people was their resilienceDespite the vicissitudes of history and the difficult circumstances through which it has had to pass, it has always known how to preserve itself and to preserve its meaning and its mission. "Ultimately this meaning was based on the particular relationship that the chosen people have with God and that tradition preserves and enriches according to historical circumstances."has written César Mora ("Gershom Scholem, rediscoverer of Jewish mysticism", El Ciervo., 2019). For Scholem, it is striking how, under very harsh social circumstances, capable of crushing him, the Jew has reconfigured and developed. He does not attribute this solely to the religious bond, for it seems to him that precisely the present era, marked by secularization, has not been able to make the common bond of the people obsolete.

For Scholem, the specificity of the Jewish people arises largely from God's choice and the message he revealed to them. This revelation is not understood as a single and final moment, but radiates and expresses itself in all of reality and throughout all of history.

Scholem understands revelation as something open-ended, pending its final configuration that will only be understood by looking back: "The word of God, if there is such a thing, represents an absolute, of which it can just as well be said to rest in itself as to move in itself. Its irradiations are present in everything that, everywhere, struggles to express and configure itself... and it is precisely in this difference between what is called the word of God and the human word that the key to revelation is found." (Scholem, There is a Mystery in the World: Tradition and Secularization, p. 18).

Therefore, revelation is understood by Scholem as something open to interpretation, an encounter of man with the word of God that is infinitely interpretable, that is configured through historical experiences and with them is renewed. Historical experience thus becomes for Judaism something fundamental, where the Jewish people finds its identity and where it encounters revelation.

One of these fundamental moments that imprints identity on the Jewish people would be the revelation of Sinai and, even today, the question about the contents of the revelation and its confrontation with the times is still valid.

For Scholem, revelation adapts itself to historical time and therefore at each moment of history this question must be asked anew and an answer must also be sought in history. Historical experiences necessarily lead the Jew to ask himself about his identity; unlike the Christian, to whom historical circumstances tell him - according to Scholem - nothing about his identity, since his configuring moment - the coming of the Messiah - has already occurred in the past. The present and the future are for the Jew open and radically related to his most intimate identity. Events such as the Shoah are fundamental to understanding Jewish identity today.

For Scholem, revelation is open to the novelty of human creativity. It is not something fixed and that should only be transmitted, but something alive, in a constant relationship with the believing conscience and open to spontaneity. Scholem sees in tradition the secret of the Jewish people, for it represents the union of the old with the new, the acceptance of novelty and its integration into what is already established.

Learning from our "elder brothers in the faith" - as John Paul II liked to call the Jewish people - is a challenge. In this direction, Gershom Scholem is an author who can help us, for he gives us much food for thought.