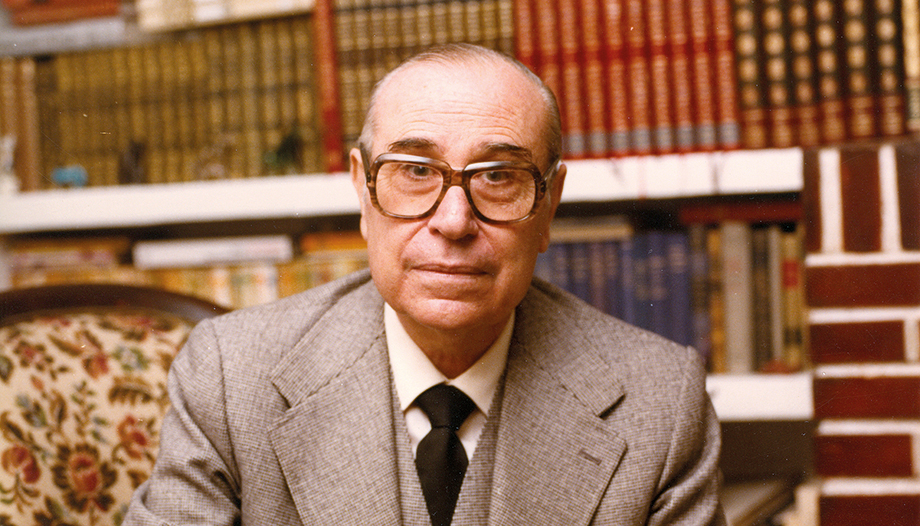

According to those who knew him, Francisco Garfias was a kind and accessible man, not haughty at all. In addition, during his lifetime he enjoyed an admirable lyrical reputation, standing out with a poetry that was very open to a wide variety of themes.

All poetry seeks God

However, her deepest verse, the one in which she reached her best literary level, was always marked by her relationship with God. In fact, those who have known and disseminated the religious lyric of the twentieth century, have kept it in mind in their works, including Ernestina de Champourcín herself, who in the third edition of her mythical collection -God in today's poetrypublished by the Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos (the BAC), did not want to do without him, a poet who, already in the Anthology of religious poetry by Leopoldo de Luis, made his poetics very clear: "If poetry is not religious, it is not poetry. All poetry (directly or indirectly) seeks God". An idea that, although it is very common in many authors, in Garfias it has the appearance of a falsehood or guiding thread in his vital and creative trajectory, even in his first book in his twenties, Interior roads, in which he reveals a constant scrutinizing orientation that, from now on, will characterize him, but which, above all, will be noticeable in his three most inspired collections of poems: Doubt, I write loneliness y Double elegy.

In his inquisitive eagerness, the presence of God is glimpsed as a continuous pulse that keeps him on tenterhooks in the face of vital questions. Thus, in his first book, the most emblematic of all, DoubtThe initial quotations from St. Paul and Unamuno, respectively, are evidence of his marked thirst for divinity and show that his is a poetry full of questions, of deep uneasiness embodied in those overwhelming verses in which he expresses his most vivid battle, after realizing that his childlike faith is slipping away like water: "Now, through the throbbing valley / of memory, hands, eyes, forehead / seek the face that one, the burning bush. But the water is not there", which is found to be: "Suddenly, without anyone noticing, / without preceding a shout or a flash of lightning, / this other light has broken my joy. / My joy has dried up. It has / clouded my hope. / Suddenly, hands, eyes, forehead, / heart and silence / have been left without God.". In this balance between faith (one light) and reason (another light), it seems as if God disappears from his life. It is, therefore, a thought-out faith that traces Garfias' personal existence; a thought-out faith that unfolds in a "subway crossing / that goes back and forth, Lord, to you, from you." and that has as a synthesis of all his religious thought the verses that close the book Doubt: "I have an unspeakable fear of turning / My faith on its back. I have a horrible fear. / Horrible, I assure you. / And through my wild night I seek, / I seek again, I repeat the call, / I stumble at God, I raise his banners, / I struggle and fall defeated in his lap. / It is that God who now / is the size of my doubt.".

Tense and confident tone

Although it may give the impression that his poetry remains there, in uncertainty, in perplexity, in an agonizing way of understanding reality, and, in the end, is that of a person searching for God in the fog, in the words of Antonio Machado, it is positive that at no time does it become incredulous or fall into a deep uprooting, but it develops permanently in a tense tone, especially because the poet, resorting to poetic images of his time - that of the "dog", for example, was already in Sons of wrathby Dámaso Alonso- expresses his most authentic inner anxieties as can be read in Sore bouqueta meaningful sonnet that is worth reproducing: "Because you wound me, I believe in you. I love Thee / Because Thou art a wavering shadow / I seek Thee for wandering and discordant / Because Thou answerest me not, I call Thee / I, wounded dog beside Thee. You, the Master / I, the bewildered and the questioning / You, the spoiler, the bewildering / I, painful branch, burning branch / You, whip hanging in my crack / Stinging in the eyes that imprison me / Living salt for my chest without bonanza / Oh, master of my being and my agony / Christ, clinging to my cross, to the candles / of my faith, of my love and my hope". And, at the same time that it is tensional, it is poetry that arises from a determined trust in God, from an enormous desire to clarify the inner situation in which the poet often finds himself. As Psalm 130 announces, Garfias' poetry is poetry that comes from the depths, like a cry, in a persevering request for grace. Thus it is understandable that he turns his verses into a constant claim when he implores divine favor: "Give me thy hand Thou if thou art still / In my amazements poured out". or sensibly insist on reaching for the light of faith, more than ever before. "when the light goes out".

After Doubt (1971), the poet publishes I write loneliness (1974), dedicated to his sister, his great confidant, who had just died. In both books, Garfias presents a lyrical and oratorical touch that, as we pointed out at the beginning, constitutes, together with Double elegy (1983), the most inspired of his poetic production. A quote from St. Augustine opens it: "In the end it is always loneliness, but behind the loneliness is God." and, then, a bouquet of compositions with a family flavor is generated in which there is room for both the gaze of the mother, her other confidant, always attentive to the performances of her children, and the reunion with her childhood and her town, Moguer. In the face of these affections -especially those of her mother and sister-, she has a special place for her children's performances. "the answer, at last, I find it again / in love, definitely".

Openness to other realities

"Let not the mighty river rest, / The dove of love, the light, the song." are verses that prelude the end of that inner process. From this point on, the poetic work of Garfias -always with unequaled skill and fluidity- becomes less clamorous, less passionate, more calm, more inclined to the celebration of contemplative landscapes found in painting or in specific places in the Spanish territory. It will be poetry that looks outside of itself, that which ceases to scrutinize the inextricable labyrinths in which the poet was involved until then, and opens up to other apparently less disturbing realities. Of course, he will still have the emotional and poetic strength of one who has left his life - as Garfias wrote in one of his first published poems - along the paths of the soul.