Many years ago, almost fifty, I was very impressed by a phrase of the Russian writer Andrei Siniavski, which I read in some cultural magazine or in some journalistic text at the end of the seventies. It went like this: "It is necessary to believe, not by the force of tradition, nor for fear of death, nor just in case. Nor because there is someone who forces us or instills fear, nor for a certain idea of humanity, nor to save the soul or to appear original. We must believe for the simple reason that God exists".. I took good note of that phrase, which challenged me for its authenticity, and I have repeated it with some frequency since then.

A few months ago I had the opportunity to read the book by Duncan White Cold Warriors -whose subtitle is Writers who fought the literary cold war- which explains in detail the vicissitudes and difficulties of writers such as Orwell, Koestler, Greene, Hemingway and so many others who took part in the literary battle against communism from the 1930s, during the Spanish Civil War, until the 1990s, when the Soviet Union collapsed. Well, in this book on the Cold War, the trial of the writer Andrei Siniavski and his poet friend Yuli Daniel in Moscow in February 1966 is described in some detail. They were accused of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda for their novels published abroad under a pseudonym.

The trial - widely criticized in the Western press - lasted three days: Siniavksi was sentenced to seven years in a labor camp in Mordovia, near the Volga, and Daniel to five. Today that iniquitous trial is considered the beginning of the Soviet dissident movement. "At that time." -Coleman wrote. "they did not realize that they were starting a movement that would help end communist rule."

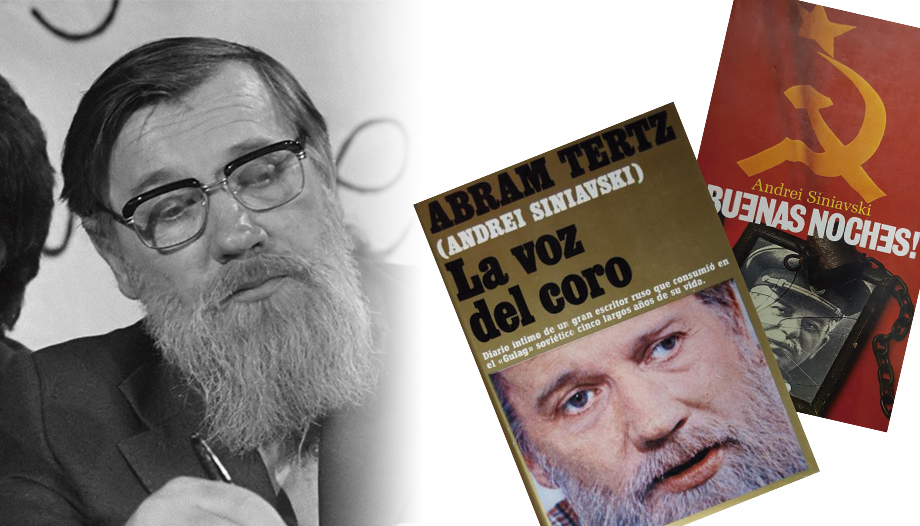

In fact, Siniavski served six years in various camps and after his release he emigrated with his wife and son to Paris. Reading in Cold Warriors of the details of the process made me look for what there was of Siniavski in Spanish. In the quarantine of the coronavirus I have been able to read slowly his book The voice of the choir (Plaza & Janés, 1978) -a mixture of diary and fine literary reflections- that has impacted me for its attentive eye for detail, for its powerful metaphors and for many other things. It has statements that reach to the depths of the soul."At all times art has been more or less an improvised prayer." (p. 24); or "Books incline us toward freedom, they invite us to set out on the road to it." (p. 38)-and dazzling metaphors. I copy only two fragments of the many that captivated me.

The first is a luminous memory of childhood: "The books resemble a window when at night the light is turned on and the room is softly illuminated, sparkling with intermittent golden patterns on the glass, curtains, tapestries and someone, invisible from the outside and hidden in the privacy of comfort, which is the secret of its dwellers. Especially when it is cold or there is snow on the street (better if there is snow), one has the impression that in the apartments melodious music sounds and intellectual fairies walk under the protection of colored screens. In my childhood, wandering at night in front of the secluded windows made my mother and I dream of a separate three-room apartment, about which she would talk to me enthusiastically, playing with me about that life in which I would be a man and could buy such an apartment [...]. We used to say: 'Let's go and see our apartment'. And before going to bed we would go for a walk through the snow-covered alleys, where we had three or four windows to choose from, varying according to their illumination." (p. 32).

In the second passage Siniavski compared his time in prison to a long train ride. He wrote it in October 1966 and gave light to me 54 years later, in the long quarantine of the coronavirus: "Psychologically, life in a prison camp resembles a carriage on a long-distance train. The train represents the passage of time, the passing of which gives the illusion that an empty existence has fullness and meaning. Regardless of what one does, the 'sentence passes'; that is, the days do not pass in vain, they act in one's favor and in the future, which gives them content. And, as in the train, travelers are very little predisposed to perform useful work, because their permanence in it depends on the inevitable, albeit slow, approach to the destination station. They can as far as possible live contentedly; play dominoes, loaf, lie back in their seats and chat without worrying about lost time. The serving of the sentence gives all things a good deal of usefulness." (p. 42).

I have finally been able to locate that quote that had moved me in my youth. It is found in a brief collection of thoughts published in French in 1968 (Impromptu ThoughtsBurgois, Paris, p. 76) and which has not seen the light of day in Spanish. I came to this booklet through a reference to this quotation made by Luigi Giussani in The religious sense: basic course on Christianity (p. 143). I add two more sentences from the same work: "Enough about man. It's time to think about God." [Much has been said about man. It is time to think of God.(p. 51), and this one: "God has chosen me." [Dieu m'a choisi] (p. 69). These are, undoubtedly, lapidary phrases that touch the heart and illuminate the head.