Among those who opposed the Nazi regime were those who refused to take the oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler when they were called to the army. Most of those who decided to take this step - knowing that it would mean the death penalty - were Jehovah's Witnesses; however, they did so out of opposition to all armed service and not specifically to National Socialism. However, a score of Catholics and about ten evangelical Christians refused, for reasons of conscience, to give "unconditional obedience to the Führer of the Reich and German People, Adolf Hitler," as required when taking the oath of allegiance.

These thirty people, executed between 1940 and 1945, remained hidden for decades; this is precisely the title chosen by Terrence Malick for the film Hidden life (A Hidden LifeThe most famous of them, the Austrian peasant Franz Jägerstätter, who was beatified by the Catholic Church in 2007, was the subject of the film. Recognition did not begin until the 1990s; only in 1991 did a Court of Justice overturn a death sentence for the first time: against Pallottine Father Franz Reinisch, currently in the process of canonization. A 1998 law began to repeal the death sentences imposed by Nazi war courts against conscientious objectors. Almost all of them have been included in the "German Martyrology of the 20th Century" or in the Austrian Martyrology since 1999.

Who were these men (women were not called up) who paid with their lives for obeying the dictates of their conscience? In general, it can be said that they were simple people who - perhaps with the exception of the priest mentioned above - went completely unnoticed: peasants, workers, office workers, artists... I would like to refer to one of them in more detail in order to -pars pro toto- show the human and spiritual mettle of men who were willing to fight against evil even at the cost of losing their lives.

Alfred Andreas Heiss was born on April 18, 1904 in Triebenreuth, a village in Bavaria that is now part of the municipality of Stadtsteinach. He was the sixth child of Johann Heiss, a weaver, and Kunigunda Turbanisch, and was baptized the following day in the Catholic church. After completing his early schooling in the village, he attended the Bamberg Trade School. In April 1918, when he had just turned 14, he began working in the Stadtsteinach municipal offices. He would later work in the health insurance department of the same town, before starting an apprenticeship in a bank and moving to Burgkunstadt on June 1, 1924, to work in the commercial department of an aluminum company. When this company went bankrupt in 1930, Alfred Heiss lost his job and moved to Berlin in search of a stable occupation.

In Berlin he obtained a position in the civil service, first at the Labor Court and then at the Berlin Public Prosecutor's Office. But also - and this is a key fact for his biography - he began to assist a well-known Berlin priest, Helmut Fahsel, as a stenographer. It was probably this encounter that led Alfred Heiss to take his faith seriously. Although he had been educated in the Catholic religion, until his departure for Berlin there is no indication that religious questions played a role in his life... or even politics. In 1932, Heiss joined the Catholic Zentrum party; as he himself will say, the reason was "my conviction, which I gained here in Berlin, that the Zentrum was the party that defended the interests of my religion." In a letter to his parents in March 1935 he said: "Defending our faith is the only thing that can be the basis for understanding between peoples and for the economic improvement it brings.

These ideas clashed with the aims of National Socialism, which wanted to impose German supremacy in Europe. Heiss criticized the National Socialist policy and ideology, especially the measures directly directed against the Church, the Germanizing and paganizing tendencies, which he considered as a clear advance of atheism; that is why he was also against the Nazi doctrine of race, which presented the Nordic man as a superior being. Heiss took part in public events in Catholic Berlin, such as the Day of German Catholics in 1934, the inauguration of the diocese by Bishop Nikolaus Bares in 1934 and that of his successor - after the sudden death of Bares on March 1, 1935 - Konrad von Preysing.

As in practically all of Germany, the Nazis also gained central positions in Heiss's hometown of Triebenreuth. In September 1934, while Alfred was on vacation there, a political discussion took place in the brewery run by the Nazi mayor Josef Degen. After being denounced for expressing opinions that "disturbed the work of National Socialist construction", he was arrested by the Gestapo; in addition to the penalty that could be imposed on him at trial, the Prosecutor's Office requested his expulsion from the State Administration. Alfred Heiss was taken to a clandestine concentration camp in Berlin, the "Columbia House". The testimony of Degen's son as a witness at the oral trial was decisive for Heiss' acquittal. However, his application for reinstatement in the civil service was rejected. He then got a modest job in the tax collection office of Berlin's Catholic parishes.

In those years Alfred Heiss intensifies his Christian practice; in a letter to his parents he comments: "In the east of Berlin there is a chapel dedicated to Christ the King. It is located in a working-class district, probably one of the poorest in Berlin. In this chapel the Blessed Sacrament is uninterruptedly exposed day and night for adoration. There are always people there for adoration. It is in that chapel that I began the year 1936". Although it is known that from June 1936 onwards he was working again in the public administration, there is little news about him during those years. The situation will change when he is called up.

On June 14, 1940, he received the letter of incorporation to the Wehrmacht and is assigned to an infantry battalion in a Silesian town called Glogau. However, he refuses to make the so-called "German Salute" ("Heil Hitler!") and to wear a uniform bearing the swastika. In his statement, according to the indictment, he says that "since National Socialism has an anti-Christian stance, he refuses to serve as a soldier for the National Socialist state. Despite the warning of the penalty imposed by law, he stuck to this refusal." Although the records of the trial have been lost, it is recorded that the War Tribunal sentenced him on August 20 to death, for Implementation of the water industry ("acts that undermine the defense force").

He spent his last days before his execution in the Brandenburg-Görden prison. There he wrote his last letter, addressed to his father - his mother had died at the beginning of July - his sister, his brother-in-law and his niece: "Early tomorrow morning I will take my last steps. May God be merciful to me. What I ask of you is to remain steadfast to Christ and his Church. Farewell. Alfred Andreas. The sentence was carried out on September 24, at 5.50 a.m.

In August 1945, the German Bishops' Conference decided that the attacks on the Church during the Third Reich should be recorded. The pastor of Stadtsteinach, Ferdinand Klopf, then wrote to the diocese of Bamberg: "Alfred Andreas Heiss was arrested for refusing military service, which he refused exclusively on religious grounds despite knowing the consequences; he was sentenced to death for 'undermining the defense force' and died bravely as a true martyr. Documents and letters are in the possession of his relatives in Triebenreuth".

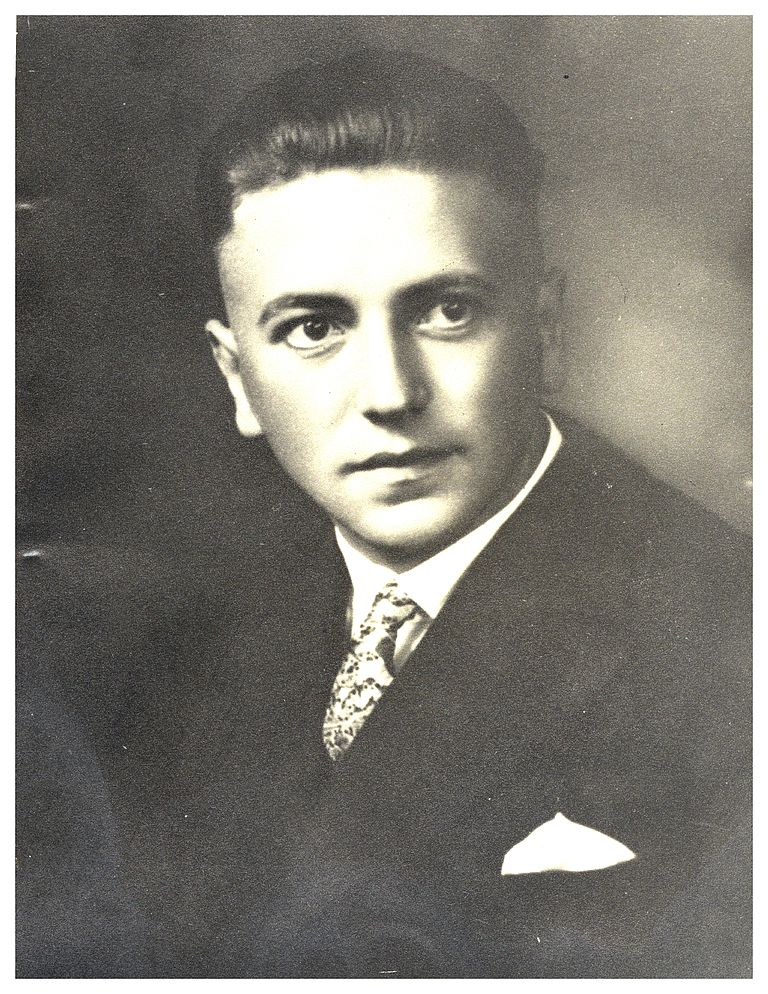

However, the bishopric of Bamberg did not take any steps at that time to restore Heiss' memory. It was his sister Margarethe Simon (1900-1981) who saw to it that, in 1957, a plaque with her brother's photo was placed in the chapel of Christ the King that had just been built in Triebenreuth. Margarethe's daughter Gretl Simon (1929-1980) and her husband Wilhelm Geyer (1921-1997) applied to the Stadtsteinach Museum for a permanent exhibition on Heiss. Anton Nagel, director of the Stadtsteinach Museum, was commissioned to design the exhibition.

It was only in 1987 that Thomas Breuer found the report of the parish priest Ferdinand Klopf in the diocesan archive of Bamberg and published it, together with the documents from the museum in Stadtsteinach, in a short booklet in 1989. As a consequence of this publication, in July 1990 a memorial plaque was placed next to those of the fallen of World War I and World War II; it reads: "In memory of Alfred Andreas Heiss, born in Triebenreuth in 1904, executed on September 24, 1940 in Brandenburg. He died for remaining faithful to his faith".

On April 24, 2014, a "stumbling stone" (a plaque that is embedded in the pavement to remember victims of Nazism, many of them Jews taken to extermination camps) was placed in Berlin's Georg-Wilhelm-Strasse in front of house number 3. The text reads: "Here lived Alfred Andreas Heiss, born 1904, who refused military service as a Christian resistance. Death sentence 20-8-1940, executed 24-9-1940, Brandenburg prison." At the laying ceremony, Maximilian Wagner, pastor of St. Ludwig's Church, gave a brief biographical sketch of his life. The ceremony ended with a prayer: "Alfred Andreas Heiss fulfilled the mission you had entrusted to him by giving his life. You have called him to you as a friend. He lives with You with a love fulfilled wholeheartedly, wholeheartedly and with all his thoughts".

Alfred Heiss and the others who refused to take the oath to Hitler remain, even today, an example of the primacy of conscience, of remaining faithful to the truth, even at the cost of one's life. More information about Alfred Heiss, and about nine other conscientious objectors, can be found in my recently published book: José M. García Pelegrín, "Mártires de la conciencia. Cristianos frente al juramento a Hitler". Digital Reasons, Madrid (2021) 192 pages. 13 € (6 € digital version).