"Why not stop and talk about feelings and sexuality in marriage?"asks Pope Francis in the exhortation Amoris Laetitia (n. 142). The question has troubled anthropologists and historians ever since Roland Barthes denounced the postponement of feelings in history: "Who will make the history of tears? In what societies, in what times has there been weeping?"

– Álvaro Fernández de Córdova Miralles, University of Navarra

Recent research has revealed the influence of Christianity on Western emotionality. Its history, forgotten and labyrinthine, must be rescued.

Few phrases have had greater repercussions than St. Paul's exhortation to the Philippians "Have the same feelings among yourselves that Jesus had." (Fl 2, 5) Is there room for a historical analysis of this singular proposal? Seventy years ago, Lucien Febvre referred to the history of sentiments as a "that great mute"and decades later Roland Barthes wondered: "Who will make the history of tears? In what societies, in what times have people cried? Since when did men (and not women) no longer cry? Why has 'sensitivity' at a certain point become 'mushy'?".

Following the cultural turn experienced by historiography in recent decades, a new frontier has opened up for researchers, which has been called the emotional turn (emotional turn). Although its contours are still blurred, the history of pain, laughter, fear or passion, would allow us to know the roots of our sensibility, and to notice the imprint of Christianity on the landscape of human feelings. In this sense, the medieval period has proved to be a privileged place to study the passage from the psychic structures of the ancient world to the forms of modern sensibility. To do so, it has been necessary to replace the categories of "infantilism" or "sentimental disorder" attributed to medieval man (M. Bloch and J. Huizinga) with a more rational reading of the emotional code that shaped Western values (D. Boquet and P. Nagy).

From the apatheia Greek to the evangelical novelties (1st-5th century)

The history of medieval sentiments begins with the "Christianization of the affections" in the pagan societies of Late Antiquity. The clash could not have been more drastic between the Stoic ideal of the apatheia (liberation from all passion conceived in negative terms) and the new God that Christians defined with a sentiment: Love. A love that the Father manifested to men by giving his own Son, Jesus Christ, who did not hide his tears, nor his tenderness, nor his passion for his fellow men. Aware of this, Christian intellectuals promoted the affective dimension of man, created in the image and likeness of God, considering that to suppress the affections was to "castrate man" (castrare hominem), as Lactantius states in an expressive metaphor.

It was St. Augustine - the father of medieval affectivity - who best integrated the Christian novelty and classical thought with his theory of the "government" of the emotions: feelings had to submit to the rational soul in order to purify the disorder introduced by original sin, and to distinguish the desires that lead to virtue from those that lead to vice. Its consequence in the institution of marriage was the incorporation of carnal desire - condemned by the Ebionites - into marital love (Clement of Alexandria), and the defense of the bond against the disintegrating tendencies that trivialized it (adultery, divorce or remarriage).

It was not a moral austerity more or less admired by the pagans. It was the path to "purity of heart" that led virgins and celibates to the highest heights of Christian leadership because of the self-mastery and reorientation of the will that it entailed.

Destroying Eros and Unitive Eros (5th-7th c.)

The new psychological equilibrium took shape thanks to the first rules that promoted ascetic exercise and the practice of charity in those "living fraternal utopias" that were the first monasteries. Clerics and monks strove to map the process of conversion of the emotions, and to reconstruct the structure of the human personality by acting on the body: the body was not an enemy to be defeated, but a vehicle for uniting the creature with the Creator (P. Brown).

The ideal of virginity, founded on union with God, was not so far from the ideal of Christian marriage based on fidelity and refractory to the divorced and polyandrous practices widespread among the Germanic societies of the West. This is revealed by the alliance between the Irish monasteries and the Merovingian aristocracy, who engraved on their tombstones the terms carissimus (-a) o dulcissimus (-a) referring to a husband, a wife or a child; a sign of the Christian impregnation of those "emotional communities" that tried to escape from anger and the right to revenge (faide) (B. H. Rosenwein).

The common mentality did not evolve so quickly. Ecclesiastical prohibitions against abduction, incest, or what today we would call "domestic violence", were not taken up until the tenth century. In no text, neither secular nor clerical, is the word "domestic violence" used. love in a positive sense. Its semantic content was burdened by the possessive and destructive passion that led to the crimes described by Gregory of Tours.

Little was known at the time about the strange expression charitas coniugalisused by Pope Innocent I (411-417) to describe the tenderness and friendship that characterized conjugal grace. The dichotomy of the two "loves" is reflected in the notes of that eleventh-century scholar: "lovedesire that tries to monopolize everything; charitytender unity". (M. Roche). This idea reappears in Amoris laetitia: "Married love leads to see to it that the whole emotional life becomes a good for the family and is at the service of life together." (n. 146).

Carolingian tears (8th-9th c.)

Relying on anthropological optimism The Carolingian reformers demanded the equality of the sexes with an almost revolutionary insistence, considering conjugality the only good that Adam and Eve preserved from their passage through Paradise (P. Toubert).

In this context a new lay religiosity emerged, which invited to a less "ritual" and more intimate relationship with God, linking with the best Augustinian prayer. Sorrow or compunction for sins committed began to be valued, leading to such pompous gestures as the public penance of Louis the Pious for the murder of his nephew Bernard (822). Then appeared the masses "of petition of tears" (Pro petitione lacrimarum): tears of God's love that move the sinner's heart and purify his past sins.

This sentiment, requested as grace, is at the basis of the gift of tearsconsidered a sign of the imitation of Christ who wept three times in the Scriptures: after the death of Lazarus, before Jerusalem and in the Garden of Olives. Merit or gift, virtue or grace, habitus ("usual disposition" According to St. Thomas Aquinas) or charism, pious men go in search of tears which, from the eleventh century, become a criterion of holiness (Fr. Nagy).

The revolution of the love (12th century)

The most audacious psychological findings occurred in two seemingly antithetical fields. While the canonists defended the free exchange of consent for the validity of marriage, in the Provençal courts the invention of the fin d'amors ("courtly love") - often adulterous - which exploited feelings of joy, freedom or anguish, as opposed to marriages imposed by lineage. Clergymen and second-class aristocrats then discovered the love of choice (de dilection) where the other is loved in his or her otherness for what he or she is, and not for what he or she brings to the spouse or the clan. A free and exclusive love that facilitated the surrender of bodies and souls, as expressed by Andrea Capellanus and experienced by those Occitan troubadours who passed from human to divine love by professing in a monastery (J. Leclercq).

The new discoveries took a long time to permeate the institution of marriage, which was folded to the political and economic interests of the lineage. Between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, the extended family (kinship of different generations) was progressively replaced by the conjugal cell (spouses with their children), due in large part to the triumph of Christian marriage, now elevated to a sacrament. The more daring canonists developed the concept of "marital affection" (affectio maritalis) that contemplated the fidelity and reciprocal obligations of the conjugal union, beyond the social function that had been assigned to it.

The road to sainthood was slower. It was promoted in the 13th century with the canonization of four married laymen (St. Homobono of Cremona, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, St. Hedwig of Silesia and St. Louis of France), who took up the lay holiness of ancient Christianity, although the spousal ideal was not reflected in the processes preserved as a specific path of perfection (A. Vauchez).

From mystical emotion to the debates of modernity (14th-20th century)

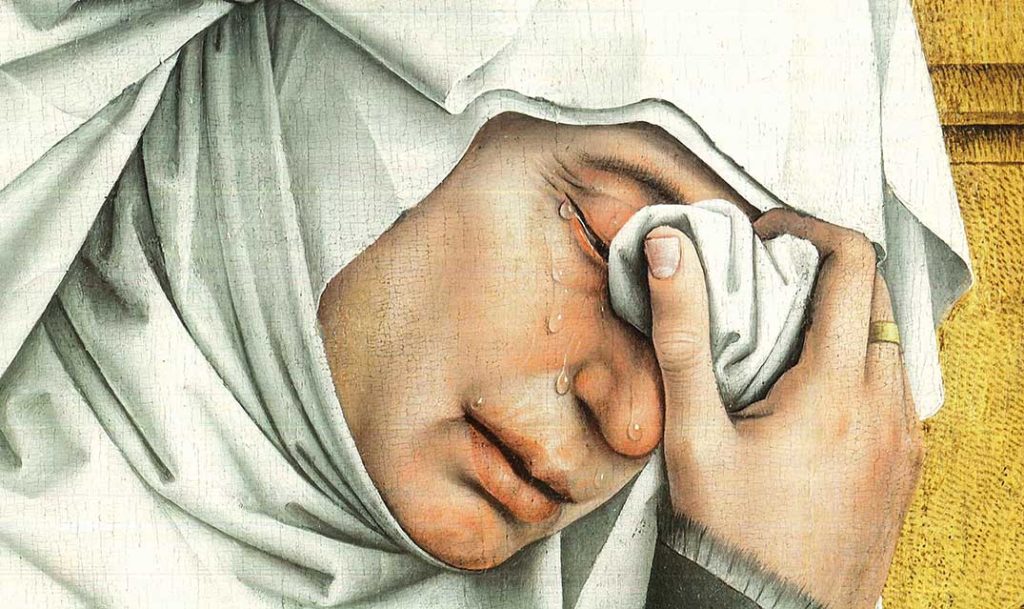

The socio-economic crisis of the 14th century modified the sentimental cartography of Western Europe. Religious devotion began to identify itself with the emotion it embodied. It was the mystical conquest of emotion. Laywomen such as Marie d'Oignies († 1213), Angela da Foligno († 1309) or Clare of Rimini († 1324-29) developed a demonstrative and sensory religiosity, charged with a rapturous mysticism. They sought to see, imagine and embody the sufferings of Christ, for his Passion acquired the central place in devotions. Never before had tears become so plastic, nor were they represented with the strength of a Giotto or a Van der Weyden.

Medieval emotions left a deep furrow in the face of modern man. Protestantism radicalized the most pessimistic Augustinian notes, and Calvinism repressed their expressions with a strict morality centered on work and wealth (M. Weber). At this anthropological crossroads, feelings oscillated between rationalist contempt and romantic exaltation, while education was torn between Rousseauian naturalism and the rigorism that introduced the slogan "children do not cry" in children's stories.

It was not for long. Amorous romanticism swept away the bourgeois puritanism of the institution of marriage, so that by 1880 the imposed unions - so opposed by medieval theologians - became a relic of the past. Sentiment became the guarantor of a conjugal union progressively fractured by the divorce mentality and an affectivity contaminated by the hedonism that triumphed in May '68. The emotional confusion of adolescents, sexual vagrancy or the increase in abortions are the consequence of that idealistic and hedonistic system. naif which has given way to another realistic and sordid call to rethink the meaning of its conquests.

– Supernatural Amoris laetitia is an invitation to do so by listening to the voice of those feelings that Christianity rescued from classical atony, oriented to family union and projected to the heights of mystical emotion. Paradoxically, the greatness of its history is mirrored on the surface of its shadows: the tears of water and salt discovered by the same Carolingians who underpinned the conjugal union. Pope Francis wanted to rescue them, perhaps conscious of those words that Tolkien put in Gandalf's mouth: "I will not say to you: do not weep; for not all tears are bitter.".