The most direct path to a meaningful existence is to discover one's own and others' vulnerability. This statement, simple in its expression, but profound in its consequences, condenses the anthropological proposal made by Professors Montoya and Giménez Amaya in a recent publication of the "Philosophy and Public Theology" collection of the Dykinson publishing house, entitled Corporeality, technology and desire for salvation. Notes for an anthropology of vulnerability.

This book is the result of years of interdisciplinary and collaborative work within the context of the Science, Reason and Faith research group of the University of Navarre.which was born from the impulse of Professor Mariano Artigas. Its content presents, together and adapted to the new format, some previous publications of its authors in specialized magazines, and does not intend to present a systematic treatise, but to establish an anthropological starting point.

This is a solidly argued academic reflection, with abundant critical apparatus and expository rigor, based on the philosophy of the Anglo-Saxon thinker Alasdair McIntyre. After an opportune introduction, which neatly gathers some concepts developed later on, he sets out his thesis in three chapters that deal respectively with the issues enunciated in the title: the corporeality and its psycho-biological contingency, the technology unfocused from their natural purposes, and the desire for salvation which opens the human being to transcendence and is presented as the core concept of the whole study.

The authors build their argumentation from a reflection on the purposes of human life, with which they understand biological fragility and its manifestations in social life. Thus they understand aging as "a meeting place for understanding man", and the virtues of care as the sphere of gratuitousness that allows us to overcome a utilitarian logic of exchange. The philosophical approach draws on many sources that are conveniently cited, and gives us an idea of the origin and development of these concepts. Throughout the paragraphs, the reader is introduced to the concepts that converge in the thesis of the book: biological contingency, metabolic vitalism, corporeal intentionality, desire for salvation, just generosity... At the same time, they are presented by two philosophy professors with previous training in the world of Engineering and Medicine, which provides a more accurate vision when facing questions related to technological evolution or the field of health.

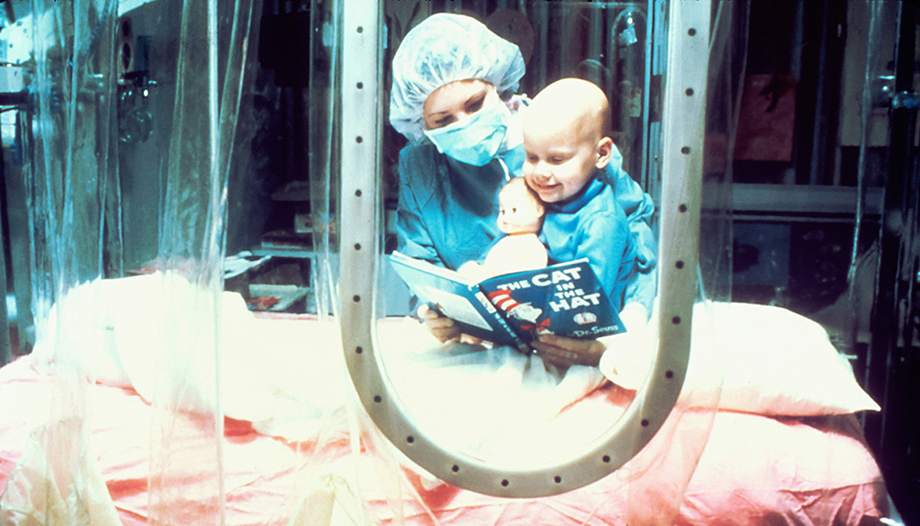

In addition, the book's interest goes beyond the academic sphere, and the authors have managed to present it with illustrative stories taken from literature with which they end each of the three chapters. These timely references to the works of Aldous Huxley (Brave New World), Mary Shelley (Frankenstein) and Euripides (Iphigenia), contribute to show the universal human implications of their study, beyond their obvious interest for specialists. The careful wording of the text makes it easy to read, and an emotionally charged cover image challenges the reader to understand that he or she is not confronted with a matter of hollow theoretical abstractions. It is taken from the painting "Hospital Visiting Day" by the French painter Geoffroy (1853-1924). The moving prologue, by Professor Javier Bernácer, is yet another proof that the proposal of this book touches the human being's fiber. Its authors have managed to arouse interest in what they understand "may be one of the most important developments in anthropological research in the coming years".

It is provocative, in these times of technological innovations, artificial intelligences, and promising announcements of the overcoming of any limit, to state without further ado that human nature is vulnerable. It is an indecent audacity for many to face aging, illness and death as a condition of humanity, an opportunity for growth and discovery of the meaning of life, and not as an untimely obstacle, a limit to overcome or an uncomfortable miscalculation in the happiness programs of efficient modernity.

Corporeality, technology and desire for salvation

From this vision, which predominates in the utilitarian mentality and enthroned health and physical vigor as the ultimate goals of existence, vulnerable life does not deserve to exist, hence the effort to suppress it from the beginning if it is detected in a prenatal diagnosis, or to facilitate its prompt elimination once the wear and tear caused by time has been verified. The search for a full life, which has directed the efforts of philosophy in the history of human thought, is reduced to full hedonism, and is satisfied with achieving a life that is not worthy of existence. pagewithout the relief that human suffering brings.

That is why I think that the authors are right in giving academic category and depth of thought to a vital expression, to an intuition that Christianity has filled with meaning from faith: weakness makes us human and in need of salvation. The pretension of absolute autonomy cannot be the ultimate goal of our life, because this conception of the human being disregards a fundamental category: relationship. Vulnerability is not the enemy to be beaten, but an inseparable companion on our journey who insists on reminding us of who we are.

In its pages we discover, with an impeccable intellectual journey, a convincing philosophical expression of the Gospel of life, so necessary to proclaim in today's world. St. John Paul II encouraged us in this task when he invited us to build the "civilization of love" (cfr. Apostolic Letter Salvifici doloris, n. 30). As Pope Francis also calls today for a "revolution of tenderness" that invites us to "take the risk of encountering the face of the other, with his physical presence that challenges us, with his pain and his complaints, a constant body to body" (Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, n. 88).