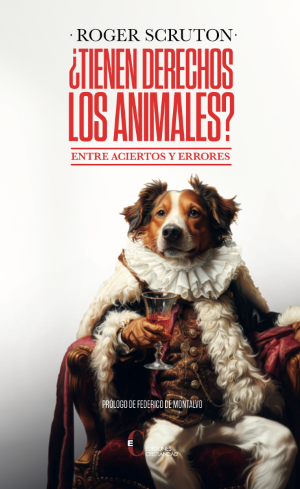

Do animals have rights? That is the question that arises Roger Scruton in a test now published in Spanish by Ediciones Cristiandad. The British philosopher purposely forgets the technicalities in this work, to give way to an accessible and incredibly luminous explanation of this debate so heated today.

Do animals have rights? Between rights and wrongs

The importance of concepts

From the very first pages, the discussion focuses on the slippery concept of rights. Federico de Montalvo writes a foreword that already points out one of the major obstacles to the issue: "The paradox of human rights discourse is that the uncontrolled proliferation of new rights and new rights holders would be far more likely to contribute to a serial devaluation of the currency of human rights than to significantly enrich the overall coverage provided by existing rights".

This importance of taking care of concepts is also pointed out by Roger Scruton in the preface, denouncing the loss of values that we suffer in the West: "The old ideas of the soul, free will and eternal judgment, which made the distinction between animals and people so important and so clear, have lost their authority and have not been replaced by better ideas".

This lack of clarity is what the author wants to solve. For that reason, he is not afraid to deal with topics such as animal sacrifice, bullfighting, zoos or hunting, unraveling concepts that we have muddled in a discourse in which sentimentality stands out more than reason or a well-defined morality.

Pets and other animals

The reader should not be fooled into thinking that Scruton does not appreciate animals and that he is bent on the superiority of man. While he points out that humans do indeed have a dominant role in the hierarchy of nature, it is that role that also demands responsibility.

And within the animal category itself there are also levels. A lion is not the same as your neighbor's dwarf dog, whether you like it or not. A dog is a pet, defined by Roger Scruton as "an honorary member of the moral community, though exempt from the burden of duty which such status normally requires."

To have affection for your cat is normal and healthy, to know that he needs you to develop is to become aware of your responsibility towards him. This idea is important to recognize that it is not enough to not harm animals and let them live in peace. The author clarifies this by saying that "if morality were nothing more than a mechanism to minimize suffering, it would be enough to keep our pets in a state of pampered somnolence, waking them up from time to time with a plate of their favorite treats. However, we have a fuller conception of animal life, which relates, however distantly, to our conception of human happiness."

Clarity in the animal debate

Chapter by chapter, Scruton addresses essential issues in the animal debate. The discussion opens on the philosophical plane, touching on the topics of metaphysics and morality. For those who want a deeper understanding, the author also offers appendices on animal husbandry, hunting and fishing, as well as a glossary of philosophical terms.

The best thing about the book is that it doesn't forget that, indeed, you think your dog is cute and leaving it in the street abandoned to its fate doesn't seem like an option. But ants disgust you and stepping on one in the street doesn't bother you at all. This does not make you a hypocrite, but it has a deep meaning that, well oriented, helps us to live the responsibility we have towards other creatures.

Without sentimentality, without extremism and with an ecological conscience, Roger Scruton has managed to shed light on a complex debate whose terms he clarifies in a brief and highly recommended book.