Samuel Sueiro: "For Henri de Lubac to do theology was to announce the faith."

Samuel Sueiro: "For Henri de Lubac to do theology was to announce the faith." Włodzimierz WołyniecOcáriz combines the study of theology with contemplation".

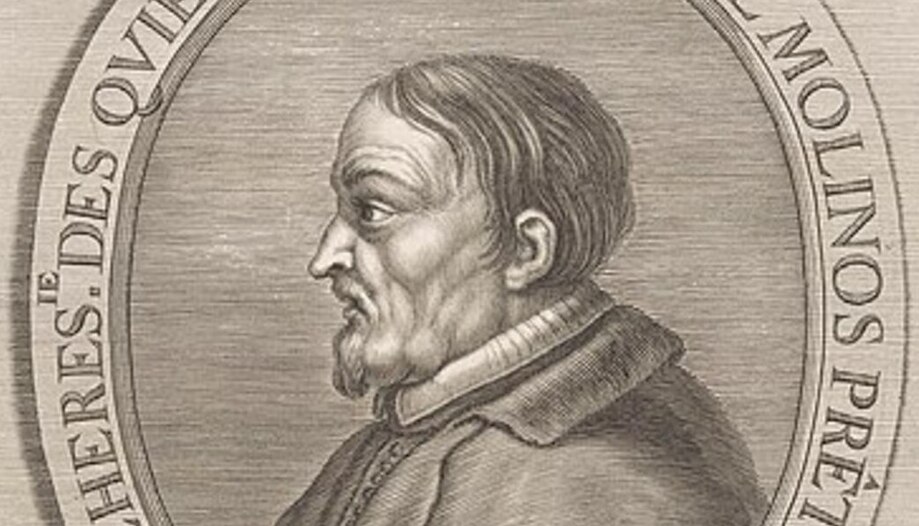

Włodzimierz WołyniecOcáriz combines the study of theology with contemplation".Sergio Rodríguez López-Ros is a member of the Royal Academy of History and Vice Rector of International Relations at CEU. A few years ago, he found in the Vatican Apostolic Library a book by the Spanish theologian Miguel de Molinos that had been missing for centuries.

This week, on May 31, 2023, the presentation of the book Miguel de Molinos. Letters for the exercise of mental prayer (Editorial Herder) in Rome, at the Spanish Embassy to the Holy See. The event was attended by the Prefect of the Vatican Apostolic Library, Mauro Mantovani, and the official archivist of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, Manuela Borbolla.

In this interview with Omnes, Sergio Rodríguez López-Ros talks about Miguel de Molinos and the discovery of the book. The history of this character is not exempt of controversy and in some aspects it is still a mystery today.

Who was Miguel de Molinos?

Miguel de Molinos is one of the most unknown Spanish historical figures. He was a theologian of the Spanish Baroque.

She was born into a middle-class family in Muniesa, a small town in Teruel. When he was 18 years old, he went to Valencia to study, because he had a sister there who was a nun. He was educated at the Jesuit College of San Pablo, which depended on the University of Coimbra, also run by the Jesuits. At the same time, she had several chaplaincies: that of the Augustinian Sisters, that of the Franciscan Sisters....

He trained with Father Francisco Jerónimo Simón, a Valencian priest. He received a doctorate in Theology and was chaplain of different convents, also confessor at the Corpus Christi College. When his spiritual master, Father Jerónimo Simón, died, Miguel de Molinos entered the process of the cause of beatification. The Deputation of Valencia sends him to Rome to carry out the process.

Thus, he arrived in Rome in 1663, at the height of the Baroque period and in the midst of the struggle between France and Spain to see who had the most influence with the Popes. At first he lived in some streets that I was able to locate.

When he arrived in Rome, he established what he had known from Father Jerónimo Simón, which was the School of Christ. It consisted of small spiritual exercises in which he gathered once a week a series of people who were rotating: on Mondays some, on Tuesdays others, on Wednesdays others... They met in a crypt, which I was also able to locate, and which is under the church of St. Thomas of Villanova and St. Ildefonso.

I was able to access this room after many centuries without anyone seeing it. Most Spanish Augustinians to this day are of Basque or Navarrese origin. They liked to play fronton and Basque pelota and used the crypt for that during the later centuries, when the name Molinos was lost.

In the past, during the time of Molinos, the high society of the time used to go there: Roman princes, counts, people linked to the papal court, cardinals...

Molinos was well positioned and, in fact, the Pope, Blessed Innocent XI, thought of making him a cardinal and had a great fondness for him.

What happens is that when one does things well one usually has enemies, envy, not only in Spain. The Jesuits, who were developing their own school with the exercises of St. Augustine, began to show suspicion towards him, and also the Dominicans.

They are the ones who provoke a first process of the Inquisition. But the six theologians appointed by the Pope gave a positive opinion, so that he perfectly saved this first attack. Let us remember that he had just published the Spiritual guidewhich is the central book of Miguel de Molinos. He had two currents: on the one hand, there was the Spiritual guidethe Carts for the exercise of mental prayer and the Defense of contemplationon the other hand, it has the Practice for the eexercise of the good death and the Defense of daily communion.

The letters were not a book. He corresponded with a lot of people, he wrote about 12,000 letters, which is a lot. A disciple of his devoted himself to compiling them. From there came the Letters for the exercise of mental prayer. They are nothing more than a simplified version, made by one of his disciples, of the Spiritual guide.

The inquisitorial process took place in 1681-1682 and, when it concluded, the ruling was favorable to Molinos. At that time, he wrote the Defense of contemplationbecause some currents wanted to attack this contemplative method.

Molinos, basing himself on St. Augustine, says that we have to seek God within ourselves, since the devil puts before us many temptations. He says that we must empty ourselves of ourselves. In that Rome of the splendor of the Baroque, of great stagings, this made them very angry and provoked envy. When the School of Christ began to spread outside Rome, throughout Italy and reached Naples, which was Spanish at the time, France was afraid that it would gain more strength and obscure the role that its mystics had been playing up to that time. Therefore, it provokes a new inquisitorial case, I suspect with corrupt methods.

The trial took place in 1685. To trace today everything that happened is very difficult, because, when the French Revolution arrived in Rome, many papers of the inquisitorial processes disappeared, and only 46 files of Molinos' processes remained. In my opinion, what France did was to slander, to attribute to Molinos things that he had never said. In fact, none of the theses for which he is prosecuted are in his writings. It is all the product of confessions either forced or falsely attributed to him by bought witnesses. Finally, the Pope had no choice but to imprison his friend, and in 1687 he decreed his condemnation for life.

He was imprisoned in the prisons of the Inquisition, in the headquarters, today the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith. During his imprisonment, Molinos wore a stoleña, a kind of sack, very austere, and led a life of recollection. He defended himself with great serenity and always reiterated his love for the Church. He also refuted any criticism that prayer supplanted the sacraments, which was one of the theses attributed to him. The bad thing is that France at that time has more strength than Spain, let's think that in 1687 the Habsburgs are disappearing in Spain, on the other hand the Bourbons, with Louis XIV at their head, are at their peak.

The process coincided with a period of decadence in Spain, while France was more thriving. In 1704 the last Habsburg died and the war began between France and Spain to see who was the successor of the Habsburgs, who were finally the Bourbons. All of this was driven by Louis XIV, who later succeeded in placing his nephew Philip V on the Spanish throne. Miguel de Molinos was so significant in Rome that to capture him and to kill him was to give the lace to the Spanish empire, it was to achieve to give Spain where it was hurting the most.

Molinos was in prison for 8 years, until he was executed in 1696. The reason why he was executed remains unknown to all of us, because the whole procedure is not known. I believe that it must have been the result of French intrigues within the Inquisition. Nor do we know if it was a settling of scores within the prison itself. In 1696 he died and with the investigation I also discovered where the remains were: in the ossuary that is just below the archive of the Dicastery itself.

How were the letters found?

I knew that there was a book by Miguel de Molinos that had been missing for centuries, which was las Letters written to a discouraged Spanish gentleman to help him to have mental prayer by giving him a way to exercise it.. The title was very baroque. The publisher summed it up as Letters for the exercise of mental prayer. It was a book written by Miguel de Molinos during his Roman period. I located the book in the Vatican Apostolic Library.

In 1966 all the books that had been considered unfit to be read by Catholics were made available to researchers. Among them were the spiritual letters of Miguel de Molinos, which had not been condemned because of doctrine, as I have mentioned, but because of a political dispute between France and Spain, because Molinos had a lot of power in Rome.

When I found it in the library, it had been 347 years since anyone had seen that book. I immediately thought of editing it and translating it. Because there are only two copies of the Spanish edition, one in the Biblioteca Nacional de España, in Madrid, and the other is the later edition made in Italy and kept in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. The book was new, the old one could be seen underneath and it was evidently from the Inquisition's collections. I always say that it is necessary to understand that the Inquisition was trying to guide people to good reading.

The people of today are very different from the people of the past. Before, no one had theological formation, first of all because they did not know how to read, and, in addition, it was not until the Second Vatican Council that people began to be formed in the faith. The role of the Inquisition was always to protect those humble people, people who had no criteria about the readings that could harm them spiritually. It was a kind of help, a guide, and it is not that which appears in the movies of scorn, torture, bonfires....

When I found the letters, what I did was to order a translation of the second edition, corrected and enlarged with respect to the first Spanish edition. They have two parts: one part in which he talks about the theological apparatus on which he bases himself, quoting St. Teresa, St. John of the Cross, St. Ignatius, the Fathers of the Church, St. John Chrysostom, and so on. Then there is a second part in which he explains how to put all this into practice.

It is very curious, because, on one occasion, he sends the book to a Spanish official, and says: "If you had every day one ratico to practice prayer, it would be very good for him. After so many years living in Italy, he still has that Aragonese touch.

The book is published thanks to the great work of the Vatican Apostolic Library. Since the time of Cardinal Javierre, who was a great cardinal, the archives have been opened.

The research has not only consisted in the publication of the book, but also in having found the places where he lived, where he did the School of Christ, where he lived when he was imprisoned, where he was tried, where he was later imprisoned and finally where he was executed and where his remains are.

What was Miguel de Molinos' thinking?

What Molinos supports comes to be the mysticism of St. Teresa: the ascetic life, simple and straightforward. He proposes an austere life, that Spanish austerity of few words, rather of deeds. Then, she seeks purgation, to remove from our life everything that is in excess, that which harms us (ambitions, power), to focus on what God wants from us. He also speaks of that last part which is contemplation, when one walks the way of the Cross, of the Passion, and tries to unite oneself to Jesus in that suffering, to configure oneself with Him, and, through that, to transfigure one's own life and become a better person. This is basically the method of Molinos, which could be exemplified with many quotations.

It is a matter of persevering in the prayerThe final objective is to become configured to Jesus, feeling that the saving and redeeming Passion of Jesus on the Cross is for all humanity, but it begins with oneself. He says that we have to kill at any cost "that seven-headed hydra that is our selfishness". He says that we have that selfishness that the devil, the will to power, puts in our hearts. Today it would be, for example, to want more money, to travel, a better car, or to have worldly success at all costs. Molinos proposes the opposite: He was simple at birth, simple in death, so let us share life with Him.

It may seem that this emptying of desire is related to Eastern spirituality, but what Molinos advocates is to turn off the ego to make room for God. Most people, from the moment they get up until they go to bed, are thinking about a better job, a better television, a vacation this summer, and they ignore the essentials. What Molinos supports is not this annihilation of desire a la oriental, in the sense that whatever happens to the world is all the same to me. Precisely what he encourages is commitment: let's leave aside what we want and let's see what God wants from us.

When the ego occupies our whole soul, our whole heart, we leave no room for God. Buddhist salvation is basically the salvation of oneself, it is more egoistic. In the Christian world, on the contrary, it is the salvation of oneself through others and for others. It is the method of St. Francis de Sales, of Introduction to the devotional life. Or when St. Ignatius proposes the synthesis between conscience and the world, it is not for oneself, but for others.

I believe that reading Molinos today is a good way to return to the simple life, to the essential, to forget about a world where everything is at our fingertips at the click of a button. But we lack the essential, we forget faith, we forget charity, hope, surrender, gratuitous love towards God, first of all, and towards others.