Intercommunion, ecumenism and interreligious dialogue is the theme of the session held on Friday, April 14, within the framework of the X Specialization Course on Religious Information promoted by the ISCOM Association, the Association of International Journalists Accredited by the Vatican (AIGAV) and the Faculty of Institutional Social Communication of the University of Rome. Pontifical University of the Holy Cross.

"More than sixty years ago, an inspired act of Pope John XXIII set in motion a change that immediately took hold and determined a new direction in the concrete life of the Catholic Church in relation to the other Churches and Christian Communions. This is what Bishop Brian Farrell, Bishop Secretary of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, said about the creation of the Secretariat for Christian Unity (today the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity), an integral part of the aggiornamento for which Catholicism had long felt a great need.

The Secretariat, under the leadership of its first president, Cardinal Augustin Bea, was charged with bringing to the Council's agenda, among other things, the pressing question of overcoming the centuries-old divisions and rivalries in the Christian world, and the restoration of that unity willed by the Lord himself: "Ut unum sint" (John 17:21). "This particular task presented itself," Farrell observes, "as a truly difficult challenge. For Catholics to participate in the ecumenical movement, which was already taking shape among Protestants and Orthodox, required a radical change of perspective on the Church, as well as on the nature and value of other Christian communities. We easily forget that the vast majority of the bishops who gathered in St. Peter's Basilica on October 11, 1962 to initiate the Council, by their formation, were convinced that outside the Catholic Church there was only schism and heresy."

In this renewed ecclesiological vision, the Council Fathers came to recognize that the other Churches and Christian Communions "in the mystery of salvation are in no way deprived of meaning and value" ("....Unitatis redintegratio", 3). Indeed, "the Spirit of Christ does not refuse to use them as instruments of salvation" (ibid.). Consequently, the duty to re-establish the unity of Christ's disciples is revealed as an indispensable requirement.

Dialogue

"The crucial question," according to the secretary of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, "was to perfect the concept of dialogue so that the results could be translated into a concrete experience of ecclesial life, as common witness and service of united love." With the Pope's encyclical Ut unum sint John Paul IIdialogue is placed in the context of a profound anthropological vision: dialogue is not only an exchange of ideas, but a gift of self to the other, reciprocally realized as an existential act. Before speaking of dialogue as a way of overcoming disagreements, the encyclical stresses its vertical dimension. Dialogue does not simply take place on a horizontal plane, but has in itself a transforming dynamic insofar as it is a path of renewal and conversion, an encounter not only doctrinal but also spiritual, which allows for "an exchange of gifts" (nn. 28 and 57)".

Dialogue presupposes, therefore, an authentic will to reform through a more radical fidelity to the Gospel and the overcoming of all ecclesial vanity. Pope Benedict XVI has further deepened the concept of dialogue, inviting us to "read the whole ecumenical task," Farrell emphasizes, "not in terms of a tactical secularization of the faith, but of a faith rethought and lived in a new way, through which Christ, and with Him the living God, enters into this world of ours today."

According to Benedict, it is necessary to overcome the confessional era in which one looks above all at what separates, to enter the era of communion "in the great directives of Sacred Scripture and in the professions of faith of primitive Christianity" and "in the common commitment to the Christian ethos before the world" (cf. Speech in Erfurt, Germany, September 23, 2011).

The exchange of gifts

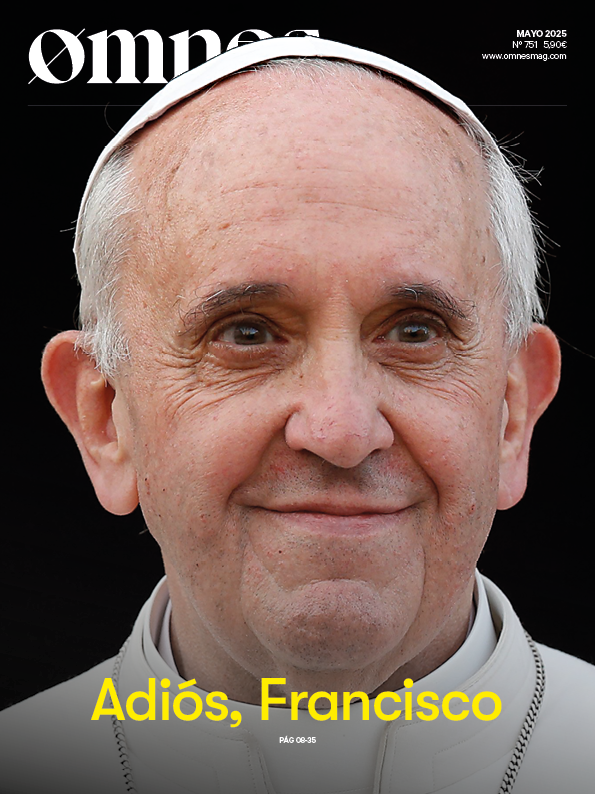

In line with his predecessors, Pope Francis has often spoken of ecumenical dialogue as an exchange of gifts. "Such an ecumenical attitude," Farrell notes, "entails an elevated theological and spiritual vision of the communion that already exists among Christians: 'Even when differences separate us, we recognize that we belong to the people of the redeemed, to the same family of brothers and sisters loved by the one Father'" (Homily of Jan. 25, 2018).

This ecumenism implies renouncing the conviction that our way is the only possible way, in order to begin to think, judge and act from the perspective of the whole Christian family, where all the baptized have a common faith.

In his report on "The Church and Other Religious Traditions: Interreligious Dialogue," Fr. Laurent Basanese S.J., Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue, recalls a passage from Pope Francis' Encyclical Letter on Fraternity and Social Friendship (October 3, 2020), no. 199: "Some try to flee from reality by taking refuge in private worlds, and others confront it with destructive violence, but between selfish indifference and violent protest there is one option always possible: dialogue. Whereas religions once flourished in relatively separate regions, today they are often found in the same territory coexisting or clashing due to ongoing globalization, making true interreligious dialogue a crucial issue.

The other

"By paying attention to what the 'different other' has in common with Christians," Basanese explains, "dialogue has introduced into the Church's consciousness and practice a new way of considering people who do not share the Church's faith. The 'other' is no longer an 'object of mission', as the old missiology treatises considered, but a subject to be addressed. Today, however, there is a desire for a more articulated and complex model of encounter, one that is multi-faceted. This model requires play, that is, discernment, among the multiple dimensions of the same reality, but also perseverance in the intention of building together a world in which peace reigns, as well as imagination and creativity in the daily life of relationships".

Recalling the milestones of interreligious dialogue in the Catholic Church (the Council and taking globalization seriously, the Encyclical Pacem in Terris, the Church's institutionalized dialogue, the 1964 Encyclical Ecclesiam Suam), Basanese dwells on the Council's 1965 Declaration Nostra Aetate on the Church's relations with non-Christian religions (n. 2), underlining the common basis of humanity from which they start: "The Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in these religions. She regards with sincere respect those ways of acting and living, those precepts and doctrines which, although they differ in many points from what she herself believes and proposes, nevertheless often reflect a ray of that truth which enlightens all men. Nevertheless, she proclaims, and is obliged to proclaim, Christ who is "the way, the truth and the life" (Jn 14:6), in whom men must find the fullness of religious life and in whom God has reconciled all things to himself".

It was the end of the Eurocentric era: new horizons were opening up for the Church's mission in the world, especially in relation to the great religions. It was impossible to separate interfaith dialogue from the peace-building process. In this regard, Basanese quotes John Paul II (Closing Ceremony of the Interreligious Assembly of Assisi, October 28, 1999): "Religion and peace go hand in hand: declaring war in the name of religion is an obvious contradiction. Religious leaders must clearly demonstrate that they are committed to promoting peace precisely because of their religious faith."

Flexible and open communities

Such a dialogue aims at reconciliation and coexistence. It is a model that opposes the "culture of confrontation" or "antifraternity". The formation of the young generations should aspire to make people and our communities not rigid, but flexible, lively, open and fraternal. This is possible by making them more complex, articulating them with the "other than themselves", increasing their innate capacity for creativity.

A dialogue thus sculpted in the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Common Coexistence (February 4, 2019): "Adopt the culture of dialogue as the way; common collaboration as the conduct; mutual knowledge as the method and criterion".

A dialogue at various levels that, according to Basanese, Pope Francis, in the spirit of Assisi, condensed well in some key concepts: "Today it is time to courageously imagine the logic of encounter and reciprocal dialogue as a path, common collaboration as conduct and mutual knowledge as a method and criterion; and, in this way, offer a new paradigm for the resolution of conflicts, contribute to understanding between people and the safeguarding of creation. I believe that in this field both religions and universities, without the need to give up their particular characteristics and gifts, have much to contribute and offer" (Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, November 22, 2019).