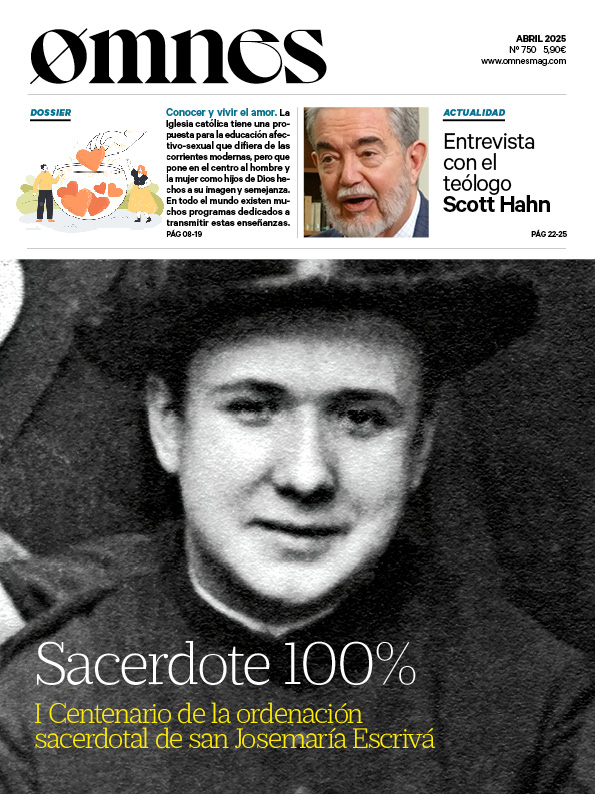

- Charlie Camosy / OSV News

Travis Pickell, author of 'Burdened Agency: Christian Theology and End-Of-Life Ethics'.The "spirituality of martyrdom" as a Christian witness at the end of life. Behind the legal pressure in favor of physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia lies a real cultural confusion about the care at the end of life, fear of loss of autonomy and fear of being a "burden" to loved ones.

Pickell is an adjunct professor of Theology and Ethics at George Fox University, and he spoke with OSV News' Charlie Camosy about. the principles on which Christian opposition to euthanasia is based.

"We're sliding down the slope'

— Charlie Camosy: Your new book with the University of Notre Dame Press, 'Burdened Agency: Christian Theology and End of Life Ethics,' is a bit unusual for an academic book in the sense that it has appeared at exactly the right time to engage the culture on a very hot topic. What is your overall opinion on the state of play regarding the debates on euthanasia and physician-assisted homicide in the United States and Europe?

—Travis PickellEarly critics of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide often cited concerns about the dangers of a 'slippery slope'. In addition to opening up possibilities for abuse, they worried that legalization of these practices would erode existing moral standards against harm and undermine physicians' sense of professional identity and purpose.

As assisted suicide continues to be legalized in new states (in the U.S.) and new countries (as it looks set to be in the U.S.), it is becoming increasingly common for assisted suicide to be legalized in new countries. United Kingdom), and as the number of people dying by assisted suicide continues to rise in places where it is already legal, we seem to be sliding down the slope.

Another slope: "tension" between justifications and restrictions

What I find even more interesting (and troubling) is a second type of slippery slope that some early critics (such as Daniel Sulmasy) pointed out: a "logical slippery slope." This has to do with the logical tension between the supposed moral justifications for euthanasia and the existing restrictions we impose on it.

For example, support for assisted suicide often appeals to a desire to minimize suffering (i.e., 'compassion') and a commitment to respect for patient autonomy (i.e., 'choices'). But if 'respect for autonomy' is indeed morally important, in what sense can we limit a person's access to assisted suicide based on a requirement that the patient demonstrate a specific form of suffering (such as 'unrelenting and intractable physical suffering') or require that the patient have a terminal diagnosis?

What is happening in Canada

Alternatively, if 'compassion' is really morally important, why should it be absolutely necessary for patients to demonstrate legal competence? Would it not be more compassionate to euthanize suffering patients who are not competent, such as some with advanced dementia, or never competent patients, such as infants with 'low quality of life' (as is legal under the Groningen Protocol in the Netherlands)?

This is precisely what is happening now in Canada, since existing requirements have been eliminated (as a terminal diagnosis) and the necessary conditions are multiplying (including a proposal to allow assisted suicide or euthanasia for all patients). mental illnesses).

Fear of being a burden or losing autonomy

- Camosy: As you know, one of the main reasons people request physician-assisted death is because, in some very real sense, they fear being a burden to others. Can you tell us more about this phenomenon?

- Pickell: This is exactly so. The slogan of 'compassion and choices' suggests that physical or mental suffering at the end of life is a primary motivation for people seeking physician-assisted suicide, but statistics suggest a different story. In one study (from Oregon in 2017), less than a quarter of respondents cited 'inadequate pain control or worry about pain' as a primary motivation. While 56 % named fear of being 'a burden' and 90 % fear of a 'loss of autonomy'.

Preparing the health system to care for the vulnerable and the dying

To me, this fact suggests three lines of reflection that we should consider. First, at a superficial level, it means that people are concerned about the very real economic cost of end-of-life care. A stay (or more than one stay) in an ICU can be incredibly expensive. A considerable portion of our total healthcare spending occurs in the last weeks or days of patients' lives, with negligible impact on morbidity and mortality.

We need to ask ourselves whether our healthcare system is prepared to care well for the vulnerable and the dying without driving many people into financial ruin. This is a crucial question for public bioethics today.

Associating 'dignity' with economic capacity: contrary to Christian convictions

But beyond that, there is also the question of what we mean by being a 'burden'. Here we need to reflect on the underlying cultural narratives that we all tend to live with, narratives that associate 'dignity' and worth with independence, capability and economic productivity. In my book, I suggest that these narratives are deeply rooted in our modern self-understanding, but are in profound contradiction with some fundamental Christian convictions.

Situation of fear and anxiety

Finally, I believe that the concern about being a 'burden' is also related to the difficulty of medical decision making at the end of life. In my book, I talk about the notion of 'overburdened agency' ((a r. note: or overburdened capacity)). That is, the idea that we are now increasingly expected to make concrete decisions about when and how we die, while simultaneously living in a death-avoiding society that does not share many cultural or religious orientations about how to die well.

This can lead to an existentially tense situation of fear and anxiety. I think some people don't want to 'burden' others with this kind of responsibility, even though, as Gilbert Meilaender once pointed out, what makes our relationships truly meaningful is bearing each other's burdens.

Help from Christian Theology

—Camosy: Readers will have to read your book for the full answer, but could you begin to outline how Christian theology can help explain and respond to what is happening here?

—PickellIn my book I spend a lot of time unpacking the cultural assumptions underlying our current end-of-life care practices. Especially the assumptions about what it means to be a moral agent and what kind of capacity is supposedly associated with a good and worthwhile life.

For short, we tend to give priority to rational autonomy or expressive individualism, two forms of capacities that are primarily active, controlling and atomistic. But, in general, things look different when we explore the Christian theological tradition.

Trusting in God and seeing death as a testimony

In Roman Catholic writings, for example, there is a constant theme along the lines of trusting God in and through one's death, of 'dying in the Lord'. As theologians such as Karl Rahner point out, this theme overlaps with Catholic teaching on martyrdom as faithful Christian witness, authenticating one's faith even to the point of death (a death, importantly, that is beyond our control).

Thus, I argue that this theological tradition recommends a 'spirituality of martyrdom', whereby all Christians can see their death as a form of witness to what it means to believe in God even unto death.

On the Protestant side, we might look to figures such as Karl Barth or Stanley Hauerwas, who emphasize the goodness of creaturely finitude and a form of cruciform and kenotic action that ultimately consists in learning to be 'dispossessed' rather than 'independent'.

Confidence, without 'taking control' of death

In general, I contend that Christian theology teaches us that we find our highest forms of flourishing in a form of submission and trust that is more 'receptive' than active (or passive). People formed and shaped in this way may be in a better position to bear the burden of their organism at the end of life without feeling that they need to 'take control' of their death in order to maintain dignity.

Practical modes: training

- CamosyWhat are some practical ways readers can ensure that their Christian theological values are reflected in their treatment and care at the end of life?

—Pickell: Philosopher Iris Murdoch once wrote, "At the crucial moments of choice, most of the business of choosing is already over." While there are certainly things we can do to advocate for affordable access to health care or for fair laws regarding assisted suicide and euthanasia, my own sense is that we also need to focus on the issue of training.

Facing agony and death

Stanley Hauerwas once quipped that "we get the medicine we deserve." Christians, whose central practices (baptism and Eucharist) revolve around death and dying, should be the ones most comfortable talking about death and dying, facing them with confidence.

Admittedly, as Justin Hawkins recently pointed out in his review of my book, empirically this does not seem to be the case. Nevertheless, I believe (and argue in the book) that Christian practices are formative, and that God can and does help us to be more receptive (although I would not suggest that they do so 'magically', but must be accompanied by good teaching and a constant recognition of the forces of malformation around us).

Medicine: from the 'art of healing' to a consumerist exchange

On the side of medical professionals, we must recognize that the core of medicine as a healing vocation is deeply challenged, especially as medicine moves from a Hippocratic (and Christian) understanding of the art of healing to a 'provider or service model', which turns medical care into an economic and consumerist exchange and empties it of its inherent telos.

The issue of training, therefore, is of crucial importance in medical education if physicians and nurses and other healthcare workers are to avoid the dehumanization that often accompanies modern medicine.

Healthcare: a Christian vocation, a human vision of medicine

For example, at George Fox University I teach a class entitled 'Healthcare and the Integrated Life,' in which students explore what it means to consider healthcare as a Christian vocation. And what it means to become the kind of person who can sustain a commitment to that vocation over time (i.e., someone who has developed virtues such as caring, compassion, courage, faith, hope and love).

This is just one of the ways in which I hope to contribute (in the long term) to a more humane view of medicine, and to help create a context for dying well.

—————-

- Charlie Camosy is a professor of medical humanities at Creighton School of Medicine in Omaha, Nebraska, and a fellow in moral theology at St. Joseph Seminary in New York.

This text is a translation of an article first published in OSV News. You can find the original article here.