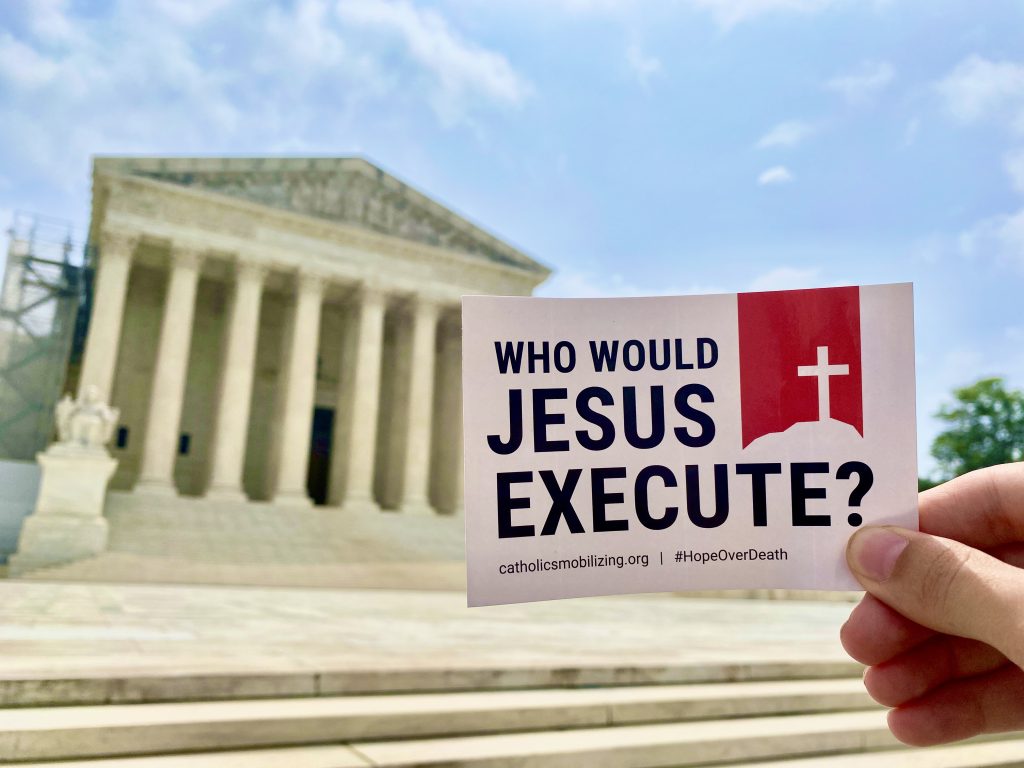

"Catholic Mobilizing Network"(CMN) is a U.S. Catholic organization that seeks to abolish the death penalty. As opposed to capital punishment, it promotes restorative justice as a "transformative and healing experience" to heal the wounds inflicted by crimes in the lives of victims and prisoners.

From "Catholic Mobilizing Network" they want to "defend the dignity of people, build just relationships, seek healing, promote accountability, enable transformation and foster racial equity."

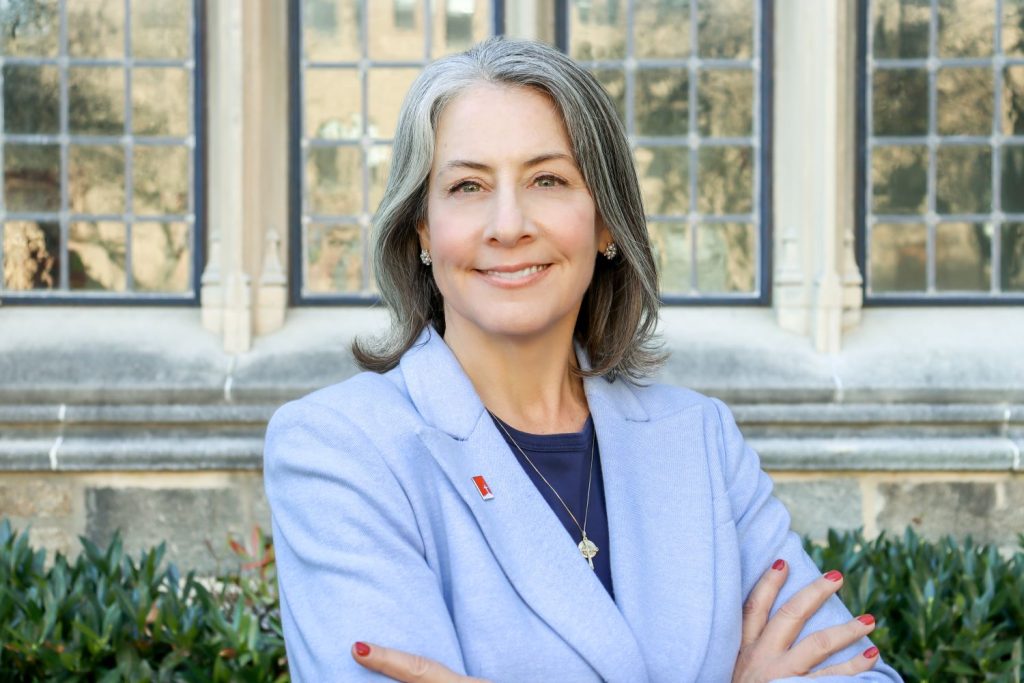

To discuss restorative justice and the work of CMN, Omnes interviewed the organization's executive director, Krisanne Vaillancourt Murphy. During the conversation, Krisanne addressed a number of issues, including the Catholic understanding of justice, the importance of not locking people into labels, and the respect due to both victims and those who committed the crimes.

What is restorative justice and why is it a good option?

- Restorative justice brings together people who’ve been affected by harm in a voluntary and safe process. This process allows everyone involved to understand the impacts of the harmful action, and what is needed to make things right. It can be a transformative and healing experience.

Restorative justice is rooted in the belief that every person — regardless of the harm they’ve suffered or caused — deserves to be treated with dignity and given the opportunity to transform hurt and suffering into healing and wholeness.

Do you believe that every person is capable of going through a restorative process?

- All harm is unique, and because of this, restorative justice is never “one-size-fits-all.” Recognizing that restorative justice always needs to be voluntary, there are certainly some cases where a person might not be ready or willing to participate.

That said, I do believe that restorative justice should be an option available to everyone. Restorative justice gives people who’ve been harmed a voice and an agency that our criminal legal system often does not. It gives people who have caused harm the chance to accept responsibility and start the process of repair in a way that our legal system often does not. On the whole, restorative justice creates the conditions where healing might actually be possible -- and that is why it needs to be more widely accessible.

I’ll add that there are ways that each of us can live more restoratively in our own lives -- it doesn’t only need to happen in cases of crime. By remembering the dignity of others and our human capacity for redemption and transformation, we all can improve our personal relationships, strengthen our communities, and rehumanize our social systems. For Catholics in particular, restorative justice helps us approach damaged relationships like Jesus would, modeling his reconciling way.

"Catholic Mobilizing Network" has three important areas: education, advocacy and prayer. Why are they important?

- CMN utilizes a three-pronged approach of education, advocacy, and prayer because change happens in our hearts, in our minds, and with our actions. We see each as equally fundamental when it comes to transforming ourselves and our broken systems.

What’s the meaning of justice? How should Catholics promote it?

– From Catholic tradition and Scripture, we understand that justice is the state of being in right relationship with God, with one another, and with all creation. Catholics can participate in the work of justice by seeking out where relationships have been broken, recognizing where there is suffering, and then beginning the process of addressing what is needed to set things right. In cases where relationships have been violated by crime or violence, restorative justice helps us acknowledge the injustice and start a process toward finding an appropriate solution.

The CMN website does not use the word "delinquent", "criminal" or any other synonym, why?

– The Catholic nun and renowned anti-death penalty advocate Sr. Helen Prejean likes to say “we’re all worth more than the worst thing we’ve ever done in our lives.” Labels like “criminal” and “offender” -- even labels like “victim” -- fail to take into account that all of us, just by nature of being human, have both caused and experienced harm in our lives. The lines between “victim” and “offender” are not so clear cut. Many people who have caused serious harm also have been subjected to it at some point in their lives.

We choose to avoid these labels because we believe that God sees us as so much more than a “victim” or “offender.” In his eyes, we are all children of God, we all have dignity, and we all are deserving of respect.

Is it possible to find a balance between the respect and justice due to the victims and the respect due to those condemned to death?

- In "Fratelli Tutti"Pope Francis writes that "every act of violence committed against a human being is a wound in the flesh of humanity. Violence leads to more violence, hatred to more hatred, death to more death. We must break this cycle that seems inescapable."

When we as a society talk about justice for victims, we know it has to involve a measure of accountability for the person who caused them harm, and a way of keeping them safe from future wrongdoing. But that does not mean we have to perpetuate the cycle of violence. We can deliver a kind of justice that doesn’t create more “wounds in humanity’s flesh.”

How to explain to those harmed by the crimes committed that the death penalty is not an option?

- Often, the best way to approach people who’ve been victimized by crime is not to speak or to preach, but to listen. With openness and curiosity, we should seek to understand the unique pain that people are experiencing. We need to accompany them in their (often lifelong) journeys of grief and healing.

I think about my friends, Syl and Vicki Schieber, whose daughter, Shannon, was tragically murdered in 1998. Syl and Vicki were told by law enforcement that the death penalty is the only thing that would bring them “closure” and peace. But it never sat right with them, this idea that killing Shannon’s killer would help them heal.

Syl and Vicki are lifelong Catholics. And it was through praying the Lord’s Prayer at Mass that they realized they could choose another path — a path of forgiveness. They made the incredibly difficult choice to forgive Shannon’s killer, and they became vocal advocates against him receiving the death penalty. They also played a major role in their home state of Maryland abolishing the death penalty in 2013.

Syl talks about how years after Shannon’s death, he met a man whose father had been murdered 20 years before. Where Syl had rejected the idea that vengeance would help him heal, this man had chosen the other path — the one of anger and resentment. At one point in the conversation, the man said to Syl, “Wow, I wish I was where you are.”

There are still too many victims waiting for the “closure” that society has promised them will come from capital punishment. We owe them the chance to break free from what Pope Francis calls “this cycle which seems inescapable.” They deserve the peace and healing that Syl and Vicki found.