Pope Francis has asked the Church to pray for migrants during the month of June. In Omnes we interviewed Nicole Ndongala, who was forced to leave her native Congo in 1998 because of the war and violence there at the time.

Although today she is perfectly integrated into Spanish society, she arrived in Madrid with practically nothing and, in the midst of the difficulties of her first days as an immigrant, on the verge of running out of money, she remembered her mother's unwavering faith and one of her usual phrases: "God never leaves us from his hand".

This led her to seek help at a nearby church. Although, to her surprise, she initially found it closed (something that, she points out, never happens in the Congo), this first contact eventually led her to the Karibu Association, an organization dedicated to helping African immigrants in Madrid. Her relationship with Karibu has taken a surprising turn over the years: she went there in 1998 looking for help and today, years later, she is the association's director.

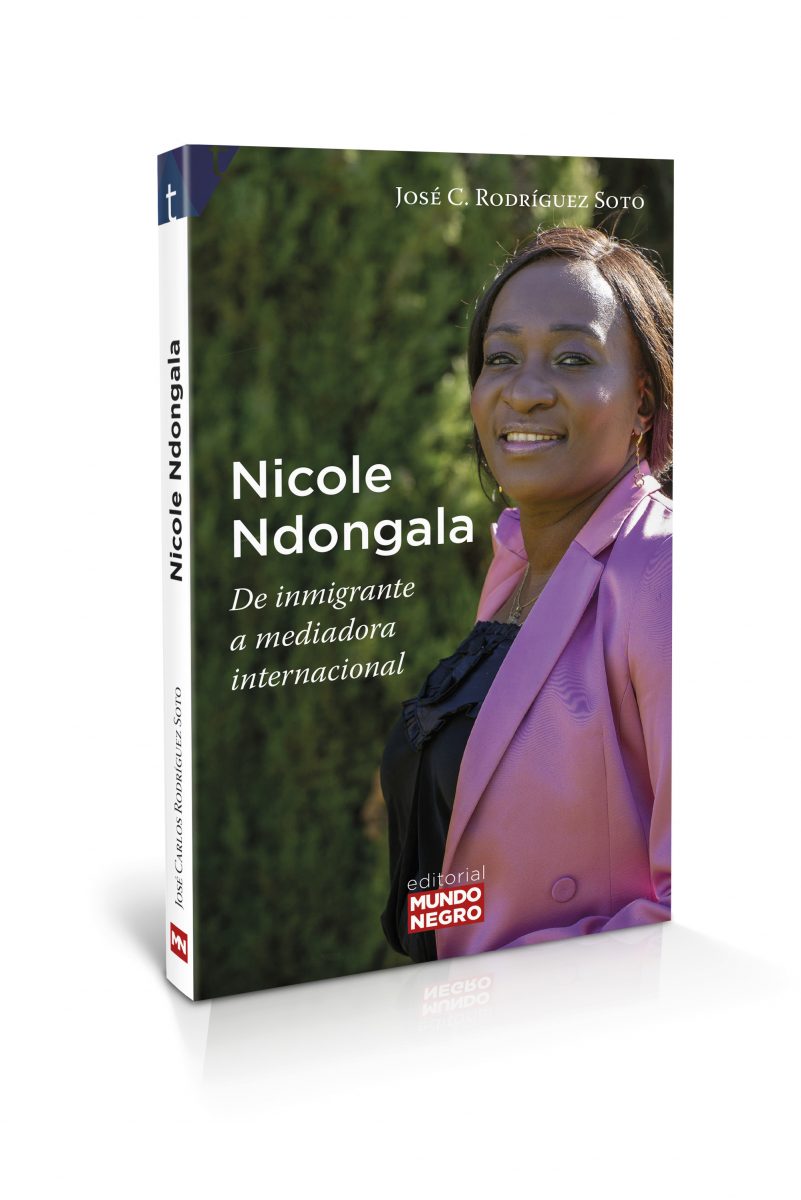

Nicole Ndongala. From immigrant to international mediator

– Supernatural Mundo Negro Publishing House has recently published a book that tells the story of this brave Congolese woman and opens us to realities such as immigration or racism, as well as showing us the differences between the Catholic Church in Spain and in the Congo.

In your case, what led you to emigrate from your native country?

I had to leave the Democratic Republic of Congo due to political instability and violence in the country. In my case, it was because of continuous threats and persecution. I was looking for a safe place to live and prosper, away from the violence. I did not want to continue living in uncertainty, with growing insecurity. Years have passed and I hope to see a Congo free of violence, because what many people continue to live has not changed much from what I experienced. There has been no reparation, and justice still does not act. Everything goes unpunished, which is what perpetuates more violence.

How was your adaptation process to Spain?

It was gradual and positive, I had to face the typical challenges of adapting to a new culture, language and environment, but with determination, perseverance and, above all, a good reception design, I managed to successfully integrate into Spanish society.

I made an effort to learn the language, since I didn't speak a word of Spanish, and I got involved in social and cultural activities from minute one.

My main support was and continues to be the Karibu AssociationI felt more comfortable and confident in my new life.

I believe that, despite the initial challenges, with determination, a positive attitude and the ability to overcome obstacles, I am finding my space. Looking back, I recognize all that I have achieved and the changes I have been integrating in this society, which is not so easy.

Her first contact in Spain with people who helped her was through the Church. Pope Francis has put a lot of emphasis on welcoming migrants. Do you think the Church is carrying out this welcoming role? Are there still tasks pending?

It is true that the Church has always been a place of welcome for migrants and refugees. While mobility is a right, the reality is that there is still much to be done.

Pope Francis has always been a strong and faithful voice in support of migrants, refugees and the most vulnerable, in his messages are present the Gospel values of care and attention to every human being.

This does not always translate into concrete actions, although many religious congregations have made an effort to accompany and assist migrants in their integration, offering emotional, material and spiritual support. However, there are still barriers and prejudices that hinder the full inclusion of migrants in society.

There are many things that remain to be done. Society in general needs to be sensitized to the importance of welcoming migrants and refugees, not only with a charitable attitude: it is necessary to recognize all the qualities, "gifts", that migration brings. In addition, it is crucial to address the structural causes of migration, such as poverty, violence and lack of opportunities in the countries of origin.

The Church has a fundamental role in advocating for more just and supportive policies that guarantee the rights of migrants and refugees. In this, it has a great challenge, since it encounters many barriers, because on many occasions they are prevented from doing good from above.

Sometimes, it is the activities and tasks of committed people who are determined to carry this message and stand by the needs of humanity.

At one point in the book, she comments that when her mother comes to visit Spain, she misses the Congo's way of celebrating Mass. Do you share this feeling?

I totally share it, I have always said it, the way of celebrating Mass in Congo with our Rite Zairois, which I believe is an inheritance left to us by the Catholic Church of the DRC, in our culture has a deep personal and spiritual meaning. This connection with music, joy, and unhurried, unhurried talking with the community after the Masses, is something special and a unique and irreplaceable moment. I am nostalgic for the way Mass is celebrated in the DRC.

As a cultural mediator, what do you think are the main social problems a migrant person faces today?

There are several. To name but a few: educational and racial discrimination, social exclusion, language barriers, lack of access to basic services such as universal public health care, job insecurity and difficulty in finding housing. They may also face problems of cultural adaptation, clash of values and lack of support networks in their new environment.

It is important to work on awareness-raising, integration and the promotion of diversity to address these challenges and promote inclusive and respectful coexistence in our societies. There is an urgent need to clean up institutions and humanize the reception system.