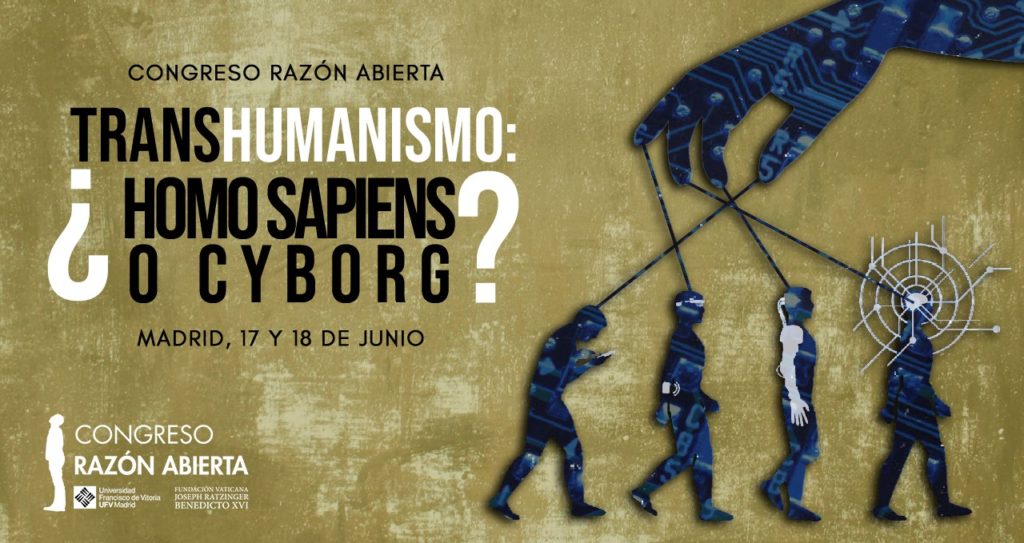

When someone asks what transhumanism is, one could answer with a prediction by the Swede Anders Sandberg, of Oxford University, when he assures that, in the near future, machines will be able to do everything the human brain does. Or when he revealed that the medal he wears around his neck contains instructions to be cryonized before he dies in the hope of being revived in a few thousand years. For these things, among others, he is qualified as a transhumanist.

Its positions do not coincide on many issues with those of the Instituto Razón Abierta, of the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, nor probably with those of the Instituto Razón Abierta, of the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria. Elena Postigo, director of the Open Reason Congress that takes place today and tomorrow at this university, both online and in person, with an ambitious interdisciplinary program. That is why it will be even more interesting to listen to Sandberg today at the inaugural conference, and to the other experts from various Spanish and foreign universities.

To dive in the transhumanism and to situate this congress, Omnes has interviewed Elena PostigoThe director of the Institute of Bioethics of the same University, who points out that "transhumanism is sometimes spoken of as if it were a homogeneous current, when in fact it is not. Transhumanism has many derivatives, some not as radical as those of the transhumanists.

About the so-called cyborg "There is also discussion," says Elena Postigo. "It would be a synthesis between organic and cybernetic. Personally, I don't share the idea of the cyborg as understood by transhumanists," she says. But let's start at the beginning.

How did the idea of holding this Congress come about? Why transhumanism?

̶ The director of the Open Reason InstituteMaría Lacalle, exactly one year ago, proposed this Congress to me, because I have an open research group on transhumanism at the university, and she thought that transhumanism could be an ideal terrain to address the issues raised by the Open Reason Congress.

The Open Reasoning Institute was born years ago at the University with the aim of promoting reflection, study and discussion among different fields of knowledge, both science, philosophy and theology, in order to achieve what Pope Benedict XVI called open reason, or expanded reason, which reflects the desire to recover the sapiential character of the university task.

That is to say, to recover what the university was, which was the integration of knowledge. We are in an era in which each knowledge studies its own, and does not take care of the rest, so we lose sight of the human being. The Open Reason Institute was born with this purpose, of a reason open to faith, which integrates the different knowledge, and which sees the issues, the cultural currents of our time, from this integrating and sapiential perspective.

We are in an era in which each knowledge studies its own, and does not take care of the rest, so we lose sight of the human being.

Elena Postigo Director of the Institute of Bioethics UFV

And I accepted María Lacalle's proposal, with a program that addresses from basic issues to more specific questions. For example, the limits of science, what problems arise for law, for the family, for all disciplines. We set up working groups by faculties, to find out what topics they were interested in, etc., and this is how the round tables of the Congress came into being. It can be said that the whole University collaborated in order to offer an integrating and critical vision of what transhumanism is, and what challenges it poses for the university and for society in general.

You speak in a thread on his transhuman twitter account Will science soon be in a position to consider this? Are we talking about science fiction or something that has the appearance of reality? Can the alternative really be homo sapiens or cyborg?

̶ This has to be approached centuries ahead. That is, as if the medieval man suddenly landed in our time. Let us imagine a 12th century man landing ten centuries later. The changes he would find would be impressive. We have to make the mental effort of the scenario posed by transhumanism a hundred or two hundred years in the future. My answer is that part of what they propose is plausible, it is not utopian, it could happen. Another part is not. I think there is a part of utopia.

I think that in transhumanism we must distinguish between science fiction things -such as, for example, resurrecting after death, cryogenics-, which I think are utopian, because they are based on wrong theoretical premises, such as thinking that the human being is only matter; and others that we can get to see. Surely there will be a stage, and we are already in it, in which we will consider the possibility of improving the human being, through genetics, nanotechnology, robotics, artificial intelligence, etc. And I think there can be a good use of science and technology.

But there are other things that are not, that I consider to be utopian, and that are not going to be realized. The challenge consists precisely in seeing where the risks are, in guiding science and technology in the service of human beings, also so as not to harm future generations. This is precisely the ethical analysis. But part of it is not utopian, and it can be achieved in a hundred or two hundred years. Another part I don't think it will ever happen.

The challenge is to see where the risks lie, to guide science and technology in the service of human beings, also so as not to harm future generations.

Elena Postigo. Director of the Institute of Bioethics UFV

What implications might transhumanism have for the human being? And for sexuality, or the family? Can you comment on anything, even if it is addressed at the Congress?

There is a relationship between transhumanism and gender bioideology. Transhumanism speaks of the dissolution of genders and sexes. There is an author, Donna Haraway, who sustains this thesis; that is to say, in the future there will be neither male nor female, there will be a cyborg that will not have sex. This has implications for the family, because transhumanism also speaks of ectogenesis, of the artificial uterus.

I am talking about transhumanism as if it were a homogeneous current, when in fact it is not. Transhumanism has many offshoots, some not as radical as those of the transhumanists. In short, it has serious implications for the family. And this is of particular concern to me. Transhumanism and gender ideology connect in a vision of human nature that looks towards self-construction, not as something given, something created, but as something that is self-constructed through my consciousness, my desire and my self-determination to be what I want to become.

Along with what we are talking about, it is also true that domotics, or robotics, can achieve important advances for the quality of life of human beings, especially if they have degenerative diseases. You have referred to this before. However, to what extent could a human construct, such as a cyborg, have emotions, feelings, even consciousness? There are ethical limits...

Science and technology are not evil. They are fruits that have come out of human intelligence, and that, in general, although they can be misused, they have been used so far for the benefit of humanity. These sciences that you point out are going to have a therapeutic use to improve the quality of life of certain people. That is unquestionable and fantastic. What we are talking about, the use of robotics, for example, is not a cyborg.

What is the problem? For example, what could happen if a computer connected to our brain were to come along and give us certain orders that could condition our freedom or our conscience? That is an ethical problem. You ask me about the ethical limits. I cannot give a single criterion now. It is necessary to see, for each of these interventions, exactly what is involved. A genetic alteration is not the same as a connection of the brain to a computer, or a nanotechnological implant, or a nanorobot. They are very different things and that is why a detailed study of each intervention is required, to see its purpose, the means used, etc.

I would say that as ethical criteria, we should always ensure respect for the integrity, life and health of people; we should also ensure that conscience, freedom, privacy and intimacy are safeguarded; and thirdly, we should ensure that all interventions are fair and do not generate more inequality. Or, for example, that they are not discriminatory. There is talk of prenatal eugenics, genetic eugenics, to cite another example.

As ethical criteria, we should always ensure the respect, integrity, life and health of people;

Elena Postigo. Director of the Institute of Bioethics UFV

As for cyborgs?

̶ What is a cyborg? On this there is also discussion. It would be a synthesis between organic and cybernetic. Personally I do not share the idea of the cyborg as understood by transhumanists. A cyborg is an entity that from its origin is an organic-cybernetic synthesis, and that does not have to be human. We are talking about a robot with organic cells, or beings that do not yet exist. And here a whole world arises, which is that of robots, of machines?

Could they ever have a conscience? My answer is no. We could simulate a human intelligence, but we could hardly simulate a creative process or an emotion. This is where we get into what a human being is, which is not just matter. From a materialistic perspective, for them there would be a continuity between a human and a more perfected robot. From a Christian humanist perspective, they are two completely different things. One is spiritual and has a life principle in itself, and the other does not.