The relationship between modern science and the Christian religion appears to be surrounded by a halo of conflict that conditions everything that is said about it. This is how it is seen by those who are convinced that there is something fundamentally wrong in one or the other: scientismists think that modern science monopolizes the truth, so that all religions must necessarily be false, except in any case a scientific version of them, such as the "religion of Humanity" that Auguste Comte tried to establish in the 19th century. At the same time, there are Christians who counterattack by recalling the null success of such attempts: they see in science at most a handful of secondary truths, which should be tied up short so as not to absolutize them, a temptation that would always be lurking.

I have devoted most of my effort to examining the history of the relationship between modern science and the Christian religion. I must say that I disagree with both positions. I am not relying on a simple hunch: I have taken the trouble to coordinate a group of specialists to analyze the pro-, anti- or a-religious attitude of a selection of 160 leading figures in all fields of positive knowledge from the beginning of the sixteenth century to the end of the twentieth. Our conclusions are categorical: during the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, practically all of them were pro-, anti- or a-religious. all the creators of the new science were believers. They were not only at the same time scientists y The work they did was almost always based on religious motivations, so that they managed to become high-level researchers. because were Christians (something similar can be said in general of second and third level scholars).

In the 19th century, a period in which the de-Christianization of European intellectuals (especially philosophers) had advanced very significantly, scientists remained for the most part men of faith: of our selection, 22 out of 32. And those attached to religion were not exactly the least representative: among them were no less than Gauss, Riemann, Pasteur, Fourier, Gibbs, Cuvier, Pinel, Cantor, Cauchy, Dalton, Faraday, Volta, Ampère, Kelvin, Maxwell, Mendel, Torres Quevedo and Duhem: the best among the mathematicians, astronomers, physicists, chemists, biologists, physicians and engineers of that time.

We all know that in the twentieth century, the spiritual disenchantment has become a mass phenomenon. However, the religious option remains the most popular among the great scientists: 16 of the 29 whose affiliation is not in doubt. Once again, the Christians are by no means a marginal group: Planck, Born, Heisenberg, Jordan, Eddington, Lemaître, Dyson, Dobzhansky, Teilhard de Chardin, Lejeune, Eccles....

Enlightenment and secularization

Data are always interpretable; we can present them in one way or another and give them all the twists and turns we want. Nevertheless - sophistry and rhetoric aside - it is difficult to avoid the following conclusions:

1ª. Modern science was born and grew in Christian Europe and not precisely by the work of dissident minorities, but by the hand of people firmly attached to that tradition (Copernicus, Képler, Galileo, Descartes, Huygens, Boyle, Bacon, Newton, Leibniz, etc. etc.).

2ª. There is not a single "Enlightenment", that is, a single movement determined to promote the development of reason and the improvement of humanity through the free use of the intellectual faculties in accordance with an emancipatory ideal. It is true that there is an anti-religious enlightenment (that of Diderot, La Mettrie, d'Holbach and Helvetius) and also a anti-Christian enlightenment (that of Voltaire, d'Alembert, Frederick II or Condorcet). But alongside them there is also another Christian enlightenment, the only one that brought modern science to its definitive maturity, both within Spain (Feijóo, Mutis, Jorge Juan...) and outside it (Needham, Spallanzani, Maupertuis, Euler, Herschel, Priestley, Boerhaave, Linnaeus, Réaumur, Galvani, von Haller, Lambert, Lavoisier...).

3ª. The process of secularization taking place in the Western world throughout modernity. in any way was caused the rise of the new science, but rather delayed for it. The scientific community, both in the sphere of the great creators and in that of the modest workers of knowledge, has always been (and still is) more pious than their social environment.

4ª. If we want to find causes historical y sociological of the modern process of secularization (leaving aside for the moment the specifically secular ones). spiritual), there are far more credible alternatives to attributing it to the development of scientific rationality. The first of these is the division of the Christian churches after the Protestant Reformation and the scandal of the subsequent wars of religion. Paul Hazard and many others have emphasized the crisis of conscience that occurred in all countries where the loss of religious unity undermined the very foundations of social coexistence (particularly in France, England and Germany). One anecdote in a million illustrates the phenomenon: in 1689 Leibniz was crossing the Venetian lagoon. The boatmen (who did not expect the German to understand Italian) planned to assassinate him, since, being a heretic, they saw nothing wrong with it: rather, it was an action as laudable as it was lucrative. Leibniz saved his life by taking a rosary out of his pocket and beginning to pray, a practice that dissuaded the ruffians from their evil intentions: at that time the story of the Good Samaritan was not considered a model to follow.

The de-Christianization of philosophers, literati and intellectuals was intimately connected with the loss of a common religious ground. Tragically, they were powerless to remedy the undeniable evils that afflicted the Church and to prevent the fragmentation of the Reformation into innumerable confessions. Again, I illustrate this with an example: the desperate cry of Erasmus of Rotterdam at the inability of his contemporaries to unite around the mysteries of the faith, instead of exacerbating hatreds: "I am not a believer in a common religion.We have defined too many things that we could have ignored or overlooked without endangering our salvation... Our religion is essentially peace and concord. But these cannot exist as long as we do not resign ourselves to defining as few points as possible and do not leave each one his free judgment in many things. Now a great many questions have been postponed until the ecumenical council. It would be much better to postpone them until the moment when the mirror and the enigma are uncovered and we see God face to face.".

The failure of the theologians of the time is pathetic. The solutions proposed by the pure philosophers, such as defining a purely natural religion, appeasing tempers by means of purely and simply "broadmindedness" or seeking alternative secular values to cement individual and collective life, proved to be unfeasible or catastrophic. In comparison, the pioneers of the new science had a much more constructive and effective attitude: they clung to the fundamental articles of faith without trying to distort them or turn them into a weapon to be used against others. They judged - quite rightly - that the task of deciphering the enigmas of the universe fostered piety, remedied the material miseries of existence and, not least, united souls instead of sowing discord.

It is striking the ecumenism that these characters showed from the very beginning: a good ecumenism, which was not based on the rejection of the dogmas that were the object of controversy, but on the commitment to add new truths in the field of the preambles of faith, which nourished admiration for the power and wisdom of God, while increasing respect for man, the most exalted creature in the universe. There are truly moving examples in this regard: the canon Copernicus remained faithful to the Catholic Church in the midst of turbulence; he only decided to publish his great astronomical work at the insistence of his bishop, dedicated it to the reigning Pope (who appreciated the detail), made use of the services of Rhaetius, a young Reformed astronomer, and found a publisher in the Lutheran Nuremberg. There was no major problem for the local theological authorities to authorize the printing of the book that a Polish Catholic offered to the Roman Pontiff. It is striking that the also Catholic Descartes lived and composed his great scientific work in Protestant Holland, or that the Lutheran Kepler was always at the service of Catholic monarchs.

Under Catholic patronage

These were not isolated cases: the first European academies of science served as a refuge for persecuted religious minorities. And there was certainly no indifferent attitude towards religion behind them: Descartes maintained a cordial correspondence with Elizabeth of Bohemia, the princess who had given rise to the terrible Thirty Years' War. When she dared to attack the convictions of the French mathematician and philosopher (mentioning a case of conversion to Catholicism, supposedly out of interest), he reacted with both firmness and tact: "I cannot deny to you that I was surprised to learn that your Highness was discomfited [...] by something which most people would find good [...]. For all those of the religion to which I belong (who are, no doubt, the majority in Europe) are bound to approve of it, even if they saw apparently reprehensible circumstances and motives; for we believe that God uses various means to draw souls to himself, and that he who entered the cloister with evil intentions has afterwards led an extremely holy life. As for those who are of another belief, [they should consider] that they would not be of the religion they are if they, or their parents, or their ancestors, had not abandoned the Roman, [so that they] will not be able to call fickle those who abandon theirs."

The aforementioned Leibniz was not only well received when he visited the Vatican, but he was offered the direction of his library if he returned to the ancestral faith. Leibniz rejected the offer, because it did not seem right to him to change religion for a worldly advantage, but, above all, because he was working intensely (first with Bishop Rojas Spinola and then with Bossuet) to achieve the reunification of Lutherans and Catholics in an ecumenical council, which was not celebrated in spite of papal support, because it was contrary to the interests of the King of France, Louis XIV.

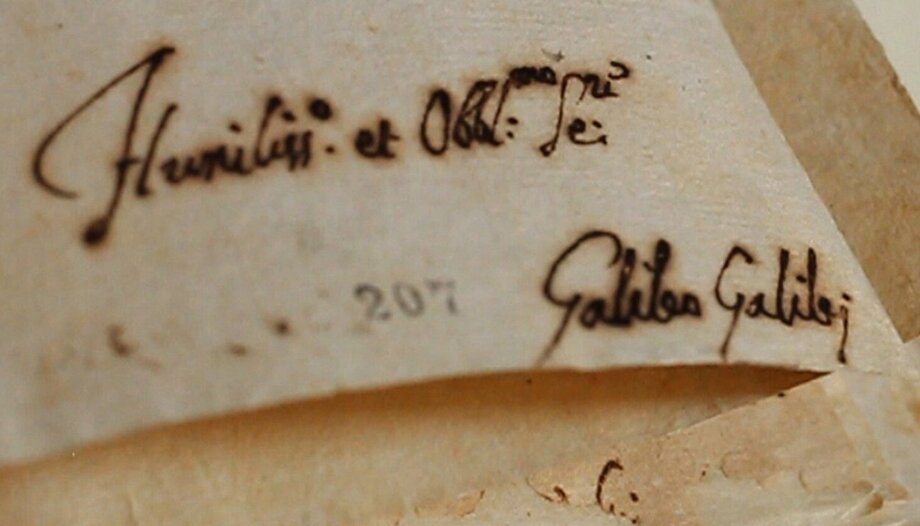

This last example brings us to the crucial point: the conflicts that arose between ecclesiastical institutions and scholars of nature, such as the cases of Galileo and the Roman Inquisition, or that of Servetus and Calvin.

The Galileo "case

Tons of ink have been spilled to discuss them (especially the first of them) and to establish the thesis of an inevitable conflict between the religious and the scientific instance. It is impossible to discuss it in depth now, but it is worth making a few remarks on which practically all scholars agree serious. First of all, they were very important events, both in the Catholic Church and in the other Christian denominations.

The positivist/scientistic historiography of the 19th century (as well as the sequels it has had until today in all those who wrote obeying slogans or mediated by ideology) took the Galileo dispute as a banner to demonstrate a supposed war (certainly not a "holy" one) between science and religion. This is the most abusive form of induction that I know of: it jumps directly from one to infinity. For there to be such a war, the list of scientists of renown (even simply of solvency) oppressed would have to be lengthened. for the scientific theses they defended. Simply by way of contextualization, it is worth remembering that throughout the 17th century, the list of famous scientists was growing, only within the Jesuit order, includes among others the following names: Stéfano degli Angeli, Jacques de Billy, Michal Boym, José Casani, Paolo Casati, Paolo Casati, Louis Bertrand Castel, Albert Curtz, Honoré Fabri, Francesco Maria Grimaldi, Bartolomeu de Gusmão, Georg Joseph Kamel, Eusebio Kino, Athanasius Kircher, Adam Kochanski, Antoine de Laloubère, Francesco Lana de Terzi, Théodore Moretus, Ignace-Gaston Pardies, Jean Picard, Franz Reinzer, Giovanni Saccheri, Alfonso Antonio de Sarasa, Georg Schönberger, Jean Richaud, Gaspar Schott, Valentin Stansel or André Tacquet.

In addition, there is the incontrovertible fact that both Galileo and Servetus were, at the same time as men of science, men of faith, as attached (or more so) to their own religious convictions as those who condemned them. Thirdly, more recent and reputable research, such as that of Shea and Artigas, has established beyond any doubt that these very concrete and limited "persecutions" were due to tactical considerations related to the exercise of power and political strategy, if not purely and simply to personal animosities. The members of the Church, even in the highest spheres, have never been free of vices and sins, and even more so in a time like that, when the main hierarchs had a power and wealth of which fortunately (it would be better to say, "the Church has never been free of vices and sins"): providentially) were stripped with the passage of time. However, it must be said that during the rise of modernity they sinned much more frequently and seriously against the demands of the religion to which they were beholden than against the interests of culture, art or science.

In short, to argue from the trial of Galileo (regrettable as it was) that the Church is allegedly hostile to the new science would be more or less like claiming that the United States is opposed to physics, given that its leaders mounted a kind of trial of the father of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer, in order to question his patriotism.

The thesis remains that modern science was born and flourished with the encouragement and inspiration of individuals who in an overwhelming proportion were fervent Christians. Was it a coincidence? I do not think so. At the end of Antiquity the pagan sages of Alexandria could very well have initiated the path that a thousand years later was trodden by the Christians of the West. But they did not. Why not? There are several converging reasons:

The Olympian contempt for manual labor displayed by the Greeks and Romans was opposed by the principle "he who does not work, let him not eat," formulated by Paul of Tarsus, apostle of the new faith while he was making tents with his own hands. Christianity sponsored from its very beginnings all honest occupations. From the slave or the farmer to the king, everyone could fit into it.

2. The pagans never conceived of a plus ultra of the universe: their very deities were cosmic. An indispensable condition of possibility for the emergence of science was the demystification of the universe, that is, the submission of nature to a superior legality. Although it took fifteen centuries to complete the task, it was the Christians who were the first to achieve it and to draw the appropriate consequences.

3. In contrast to the cyclical conceptions of time, dominant in the first European civilizations and in exotic cultures, modern science needed to start from a linear conception. It was also the Christians who contributed it.

4. The notion of natural law is indispensable for the unfolding of the new science. The idea of a transcendent God, creator and legislator was the matrix from which it emerged.

The Pythagoreans had already conceived of the world in terms of mathematical forms and structures. However, most mathematical equations are too complex for the human mind to be able to solve. Undoubtedly God could have created a universe much more complicated than this one, but then it would be beyond our capacity of comprehension. Also a more perfect one from the mechanical point of view, but then it would be uninhabitable. It is not the least contribution of religion to have aroused in researchers the conviction that the world is relatively simple to understand, despite the fact that it possesses sufficient complexity to house beings as sophisticated as us.

If the story I have told were true, why are Christian scientists in a minority today? The reason is quite simple: the birth of the new science required an intellectual and spiritual temperament that only Christianity was able to provide. Once it had been set in motion and its enormous potentialities had been proven, it was no longer necessary to be imbued with the founding spirit. Apart from the great creators, men of science are not of a special breed: children of their time, they generally share the dominant values and beliefs. They are only somewhat more hard-working, more realistic, less cynical and disenchanted than the average of their contemporaries: this is the heritage that remains of the Christian roots of science, a heritage that could, however, be lost if the present civilization persists in the nihilism that generates its estrangement from God. It is no less sad that many Christians have detached themselves from science as if it were something foreign or hostile to them. This can only be explained by ignorance of how this great enterprise was born and what continues to be its profound vocation. How to overcome this estrangement? By shaking off their indolence and assuming once and for all the demands that come from committing themselves to Christ.