Francis' invitation to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan. had been not to lose "confidence" and to nurture the "hope" that a meeting would take place, as soon as conditions permitted.

It was July 2, the day the Pope was scheduled to leave, until July 7, "for a pilgrimage of peace and reconciliation" in those lands, which was later postponed to allow for the knee treatment the Pope was undergoing at the time.

"Do not let your hope be stolen!", Francis then asked in a video message addressed to those populations, in which he expressed his regret "for having been forced to postpone this long-desired and long-awaited visit".

To them he entrusted the great mission of "turning the page to open new paths" of reconciliation, forgiveness, peaceful coexistence and development. And to these lands the Pope had sent Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin to "prepare the way".

The moment has arrived: on Tuesday, January 31, the Holy Father's visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan officially begins.

Anselme Ludiga, a Congolese priest of the Diocese of Kalemie-Kirungu (former pastor of St. John Mary Vianney in Kala), and Father Alfred Mahmoud Ambaro, a South Sudanese priest of the Diocese of Tombura-Yambio and pastor of Mary Help of Christians in the city of Tombura.

South Sudan, yearning for peace

Father Alfred, who has been in Rome for four years and holds a degree in Psychology from the Salesian Pontifical University, recalled "the drama of the war and the consequent humanitarian emergency in South Sudan, so much so that it led the Pope to summon the highest South Sudanese religious and political authorities together with the Archbishop of Canterbury to Casa Santa Marta in April 2018 for an ecumenical spiritual retreat."

President Salva Kiir and the vice-presidents-designate, among them Rebecca Nyandeng De Mabior, widow of South Sudanese leader John Garang, and Riek Machar, leader of the opposition, went to the Vatican. "Those days were crowned by the Pope's unprecedented and striking gesture of getting down on his knees," Father Alfred continued, "at the end of a speech in which he implored the gift of peace for a country disfigured by more than 400,000 dead, and then kissed the feet of South Sudan's leaders. "May the fire of war be extinguished once and for all," the Pontiff said, reiterating once again his desire to visit the country.

12 million inhabitants of South Sudan, the current president is Catholic, as are the vast majority of citizens, mostly pastors and farmers. Six dioceses, one archdiocese, all bishops are duly appointed.

These are some of the figures recalled by Father Alfred Mahmoud Ambaro, not without first drawing attention to the fact that "South Sudan separated from Khartoum with the 2011 referendum, after almost fifty years of war".

The peace treaty between the two states marked a milestone in the separation of the southern region of Sudan. A five-year transitional period, during which Juba would have enjoyed broad autonomy, was to be followed by the referendum on self-determination, in which 98.83% of voters voted in favor of secession.

The new state is crippled not only by conflict, but also by a prolonged famine, which has caused 2 million deaths and 4 million refugees and displaced persons. The infrastructure is almost completely destroyed. Added to this is a weak welfare state that has to cope with various humanitarian emergencies. Hence the ethnic conflicts that erupted between 2012 and 2013, especially in the Jonglei region.

Economically, oil accounts for 98% of South Sudan's revenue". With the disintegration of Greater Sudan, 85% of crude oil reserves remained in the South, but the only usable pipelines are through the North.

The dispute over the "right of way", for which Khartoum demanded a high price, led the Southern government to halt extraction from January 2012 until March 2013, when it resumed following a new agreement with Khartoum.

Even today - adds Fr. Alfred - the skirmishes between ethnic groups persist. In politics, they are reflected in the tensions between President Salva Kiir Mayardit (Dinka), Vice President Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon (Nuer) and opposition leader Lam Akol Ajwin (Shilluk).

In August 2022, the U.S. decided to end support for the monitoring mechanisms of the peace process in South Sudan precisely because of the inability of national leaders to find agreements to implement their international commitments."

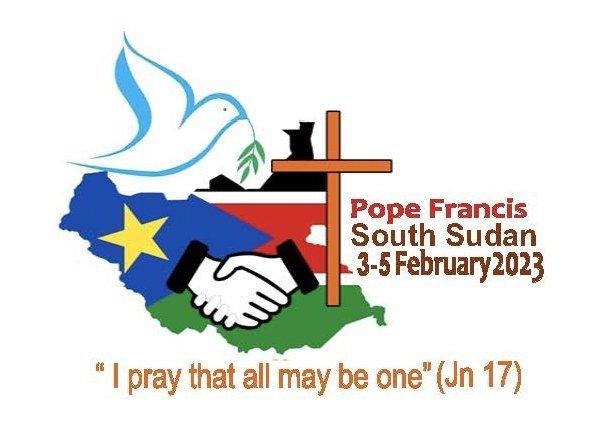

The hope is that Pope Francis, concluded the South Sudanese priest, will be able to respond to the expectations raised by the very motto chosen for his trip, taken from the Gospel of John: "I pray that they may all be one" (John 17).

The logo contains the dove, the outline of the map of South Sudan with the colors of the flag, the cross and two intertwined hands. All symbolic images. Above the contours of the map of the country appears the dove, carrying an olive branch to represent the desire for peace of the Sudanese people. Below the dove are the outlines of the map of South Sudan with the colors of the flag. In the center, two hands intertwined to represent the reconciliation of the tribes that form a nation. Finally, the cross, depicted on the right, to represent the Christian heritage of the country and its history of suffering.

The Church of the Congo, watered by martyrdom

For his part, Father Anselme Ludiga, student of Communication at the Pontifical University of the Holy Crossshared some reflections on the apostolic journey to the Democratic Republic of Congo, mentioning first of all the historical events related to the evangelization of the country, which "dates back to the end of the 15th century when, in May 1491, Portuguese missionaries baptized the ruler of the kingdom of Kongo, Nzinga Nkuwu, who took the Christian name of Joao I Nzinga Nkuwu. In turn, the court and the inhabitants of the kingdom converted to the ruler's religion.

The capital kongo also changed its name from Baji to San Salvador. In 1512, the kingdom of Kongo (the former name of the country that would later become the Congo) established direct relations with Pope Leo X, after sending a delegation to Rome headed by King Alfonso's son, Henry. He was consecrated titular bishop of Utica by Pope Leo X in 1518, becoming the first bishop of black Africa.

During the 16th century, missionary work continued in the Kingdom with the arrival in 1548 of four Jesuits to open a college. The growth of Catholics led the Holy See to erect the diocese of San Salvador in 1585, followed by that of Manza-Kongo at the end of the century. With the creation of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith ("de Propaganda Fide") in 1622, a new impetus was given to the mission in the kingdom of Kongo and in neighboring Angola, with the sending of a Capuchin mission in 1645.

In 1774, the mission of the French secular priests began. A setback for missionary action - Father Anselme emphasizes - occurred in 1834, when Portugal, to whom the evangelization of the Kingdom had been entrusted, suppressed the male religious orders in the overseas possessions and in the metropolis.

Missionary action was resumed in 1865, when the French Fathers of the Holy Spirit (Spiritans) began their mission in the Kingdom. With the beginning of the Belgian penetration, other missionary orders arrived in the Congo: Missionaries of Africa (White Fathers) in 1880; Missionaries of Scheut in 1888; Sisters of Charity in 1891; Jesuits, who returned for the second time in 1892.

The missionary work bore fruit: in 1917 the first Congolese priest was ordained. In 1932 the first Conference of the Episcopate of the Belgian Congo was held. The Catholic Church is also credited with founding the country's first university, Lovanium University, opened by the Jesuits in 1954 in Léopoldiville, now Kinshasa. In 1957, the first faculty of theology in Africa was created.

In the 1950s the local clergy was consolidated. In 1956 the first Congolese bishop, Bishop Pierre Kimbondo, was consecrated. In 1959, Monsignor Joseph Malula was appointed Archbishop of Léopoldiville and, ten years later, Cardinal.

Anselme Ludiga concludes his interesting and timely historical excursus, "the Church went through a difficult period due to the nationalist policy of President Mobutu, who, in the name of a return to the "authenticity" of the local culture, opposed the Catholic Church, considered as an emanation of European culture.

The Church reaffirmed its mission and its inculturation in the local society through the document "L'Eglise au service de la nation zaïroise" in 1972 and, in 1975, the document "Notre foi en Jésus Christ". After the nationalization of Catholic schools, in 1975, the Congolese Episcopal Conference published the "Déclaration de l'Episcopat zaïrois face à la situation présente" (Mobutu had changed the name of the country to Zaire).

The two visits of Pope John Paul II, in 1980 and 1985, revitalized the local Catholic community. The second visit of Pope John Paul II took place on the occasion of the beatification of Sister Clementina Anuarite Nengapeta, martyred in 1964.

In 1992-94, an important recognition of the social role of the Catholic Church was the attribution of the presidency of the National Sovereign Conference for the Transition to a Democratic System to Archbishop Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya, Archbishop of Kisangani and current president of the Episcopal Conference of Congo.

Finally, some data related to the current situation of the Catholic Church: 90 million inhabitants of the Congo today, more than half of whom are of the Christian faith. 48 dioceses, 6 ecclesiastical provinces, 44 ordained bishops, more than 6000 priests.

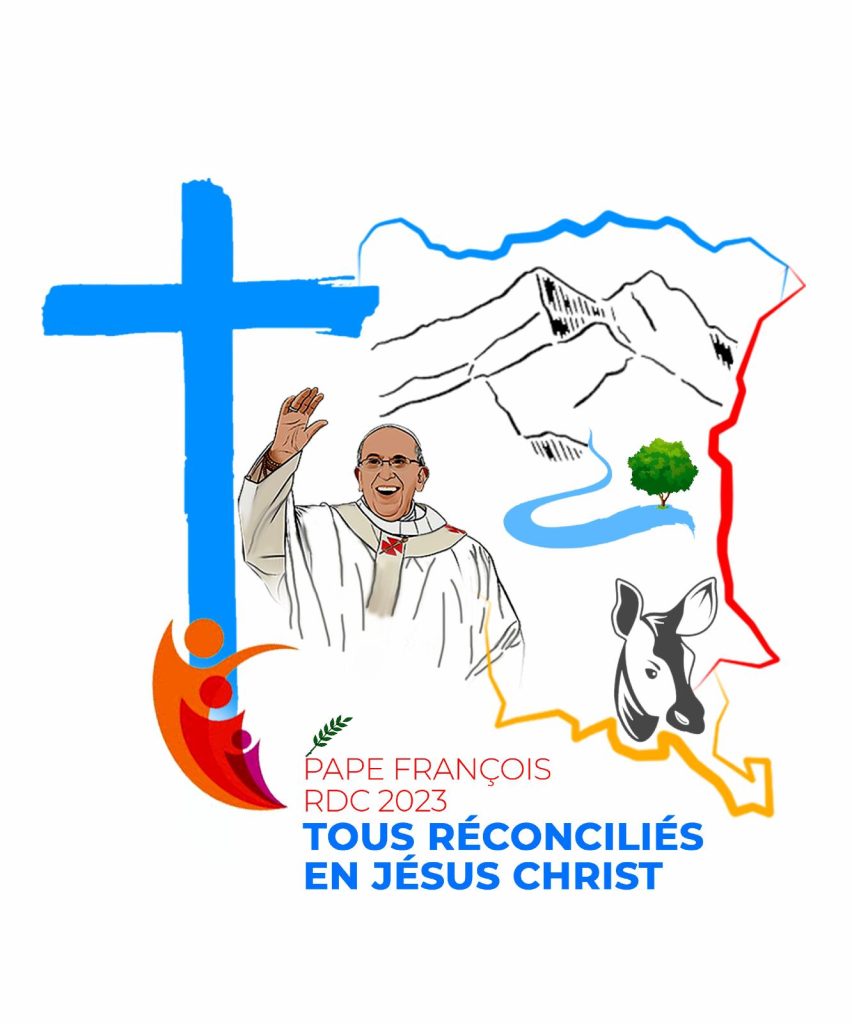

All reconciled in Jesus Christ" is the motto of the trip to the Democratic Republic of Congo, whose logo shows the Pope in the center of a map of the country that reproduces the colors of the flag. Inside, some elements of the biodiversity of the Congolese land.

The map," explains the organizing committee, "is open to the West to show the welcome given to this great event and the fruits it will bear; moreover, the colors of the flag, skillfully distributed, are very expressive. The yellow color, in all its aspects, symbolizes the richness of the country: fauna and flora, terrestrial and subway. The red color represents the blood shed by the martyrs, as it is still happening today in the eastern part of the country. The blue color, in the upper part, wants to express the most ardent desire of every Congolese: peace.